Preachers, fighters, and crusaders

BARBARA HECK (1734–1804) and PHILIP EMBURY (1729–1775)

Barbara Ruckle Heck and Philip Embury were Irish immigrants and cousins who shared much in common: their native home of Ballingrane, Ireland; a zeal for Jesus inspired by John Wesley; and common passage to New York in the 1760s as some of the very first Methodists to arrive in the New World.

Embury, however, got off to a slow start practicing Methodism in his new home. The story goes that in 1766, Heck walked in on her cousin playing cards—a frowned-upon practice for a former Methodist preacher from Ireland. She tossed the cards into the fireplace, saying “Philip, you must preach to us or we will all go to hell, and God will require our blood at your hands.”

Embury returned to preaching, starting at his own house with a congregation of five. By 1767 the congregation began renting a rigging loft (so-called because the space was used to rig ships’ sails). A year later, they constructed the spacious Wesley Chapel on John Street—it could hold between 1,200 and 1,400 worshipers—among the earliest Methodist meeting houses in America. A later building (1841) still houses John Street United Methodist Church on the same spot.

Loyal to Great Britain and sensing revolution in the air, Heck, Embury, and other Irish Methodists left New York City in 1770. As they traveled, they founded Methodist societies. Embury moved to Upstate New York, where he soon died in a mowing accident. Heck (whose husband, Paul, served for a time in the British Army) eventually wound up in Upper Canada where she died in 1804, an open Bible in her lap. Her grave marker reads: “Barbara Heck put her brave soul against the rugged possibilities of the future, and under God brought into existence American and Canadian Methodism.”

HARRY HOSIER (c. 1750–c. 1806)

Though born into slavery, Harry Hosier, also known as “Black Harry,” gained his freedom during the Revolution and became one of American Methodism’s most remarkable preachers. Hosier traveled the circuit with some of the best-known early Methodist preachers: Francis Asbury, Thomas Coke, Richard Whatcoat, and Freeborn Garrettson. Asbury once acknowledged that the best way to attract a large congregation was to announce that Hosier would preach. He and Richard Allen (see “My chains fell off,” p. 21) were the two nonvoting African American representatives at the MEC’s official founding.

Hosier could not read or write but possessed an unusually retentive memory. He refused offers to learn to read, fearing it might take away his gift of preaching. Observers reported that his preaching flowed forth eloquently in almost flawless English and in beautiful cadence, weaving in remembered Scripture and hymns.

In 1786 Hosier accompanied Asbury to New York City and preached at John Street Church. An article in the New York Packet, taking the first official notice of Methodism in the city, spoke of Hosier as “an African whose excellent preaching excited more interest than that of the Bishop [Asbury].” Oxford-educated Thomas Coke exclaimed, “I really believe he is one of the best preachers in the world. There is an amazing power [that] attends his preaching, though he cannot read; and he is one of the humblest creatures I ever saw.”

JARENA LEE (1783–?)

One of the earliest-known African American women preachers, Jarena Lee would let nothing—including illness at sea, restrictions against women preaching, and the hazards of traveling without male protection in nineteenth-century America—prevent her from preaching, often before racially mixed audiences.

Born February 11, 1783, in Cape May, New Jersey, to free but poverty-stricken parents, Lee was sent to work as a servant at the age of seven. Tormented with doubts about the destiny of her soul, Lee converted to Methodism at the age of 21 under the preaching of AME founder Richard Allen, but assurance eluded her for a time. Worries nearly drove her to suicide until she heard of the doctrine of sanctification. Lee soon experienced what Methodists called a new birth and freedom from sin’s power thanks to the Holy Spirit’s indwelling. Firmly rooted in Christ, Lee felt free to follow her call despite resistance from the church’s male hierarchy.

Lee’s eloquence and fervor won over no less than Richard Allen. Allen, struck by Lee’s off-the-cuff exhortation during a guest pastor’s sermon, decided that she was called to preach as much as any man and authorized her to do so.

When and where Lee died is unknown. Her autobiographical work, Religious Experience and Journal of Mrs. Jarena Lee (1849), still makes for compelling reading.

PETER CARTWRIGHT (1785–1872)

Cartwright once called himself “God’s plow-man.” No wonder. A chief player in the drama of American Christianity’s westward expansion, he claimed to have personally baptized 12,000 adults and children over a more than 50-year ministry.

“It is true we could not, many of us, conjugate a verb or parse a sentence, and murdered the King’s English almost every lick,” Cartwright later wrote about himself and his fellow circuit riders. “But there was a Divine unction attended the word preached, and thousands fell under the mighty power of God.”

Cartwright felt tugged by the Spirit to the distant highways and byways of Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee, and Kentucky: preaching appointments hundreds of miles apart, with few paths to mark the way. Revivals could be dangerous occasions thanks to thugs and rowdies. A good fist (sometimes the preacher’s!) might accompany a good word.

Cartwright was the man for the job. According to his autobiography, frontier danger attended him almost literally from the cradle. Converted at a revival in 1801, he soon grasped the psychology of revivals—and brought to them his powerful voice, gift for storytelling, sharp wit, and profound conviction.

Cartwright’s hatred of slavery led him to best Abraham Lincoln in an 1832 run for the Illinois Senate. Nevertheless, Cartwright opposed abolitionists, whose radical tactics he thought un-Christian, and believed that moral persuasion would best end slavery and preserve the Union.

Cartwright’s Autobiography (1857) even impressed Charles Dickens. “If we cannot love him for his meekness, nor admire him for his refinement,” Dickens wrote, “at least we must honour him for his truth, and respect him for his zeal.”

JAMES BUCKLEY (1836–1920)

Known as the “Wit of Methodism,” James Monroe Buckley’s fame was such that one ministerial colleague remarked, “General Conference does not begin until Dr. Buckley sits down.”

A keen observer of national and international affairs, Buckley regularly traveled abroad in France, Germany, and Russia. His prolific writings ranged from debunking faith-healing movements to the art of oratory to abundant practical advice to young men. In Oats or Wild Oats?, he counseled them to work hard and avoid alcohol, expensive amusements, and indiscreet young women. Buckley’s contemporaries claimed him to be the only Methodist to have written as many words as John Wesley.

Born in Rahway, New Jersey, Buckley distinguished himself even before his conversion by restless energy and a capacity to argue convincingly almost any side of any question. He flirted with the antireligious ideas of Thomas Paine and Voltaire while studying law; Christian friends despaired of ever arguing Buckley into faith until his ill health and a revival combined to force a breakthrough in 1856.

Opposed to women’s suffrage and to innovations in Methodism that ranged from women’s ordination to individual Communion cups, Buckley was sometimes characterized as the “Captain of Conservatives.” During his long tenure as editor of Methodism’s widely read Christian Advocate, he launched a campaign for the construction of the Methodist Episcopal Hospital in Brooklyn, which inspired the building of other hospitals nationwide.

FRANCES WILLARD (1839–1898) and CHARLES FOWLER (1837–1908)

“Dr. Fowler has the will of a Napoleon, I have the will of a Queen Elizabeth.”

So wrote famed Methodist Frances Willard in 1874 of her relationship with Charles Henry Fowler, former fiancé turned implacable opponent (and brother of Jennie Fowler Willing; see “Doing ‘more beyond,’” pp. 32–34). As Northwestern University’s new president, Fowler used his authority to undermine Willard, dean of the Women’s College. Fowler won the battle—he weakened Willard’s authority, forcing her to resign—but Willard won the war.

The two had met while Willard was teaching during the early 1860s at Northwestern Female College (now Northwestern University) and Fowler was studying nearby at Garrett Biblical Institute. For the first time, Willard felt valued for her mind. Nevertheless, she broke off the relationship, finding their personalities incompatible.

Willard found a new calling in social activism. By the 1890s, her reputation would eclipse Fowler’s impressive accomplishments as a pivotal president of Northwestern University and as an MEC bishop.

Her efforts as leader of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, not only to ban alcohol but also to reform gaping economic inequalities of the Gilded Age and to argue for women’s right to vote, made her a household name indeed comparable to that of Queen Elizabeth. Not merely Prohibition and women’s suffrage but also many twentieth-century social welfare policies can be traced to her leadership. “The world is wide,” she famously said, “and I will not waste my life in friction when it could be turned into momentum.”CH

By Gary Panetta and Kenneth Cain Kinghorn

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #114 in 2015]

Gary Panetta is a graduate student at the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary. Kenneth Cain Kinghorn is professor of church history emeritus at Asbury Theological Seminary and author of The Heritage of American Methodism.Next articles

The patriarch broods over his family’s future

Asbury warned Methodists against settling down like other churches

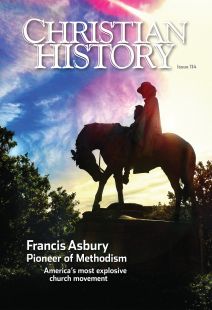

Francis AsburyThe continent was their parish

Christian History talked with historian Russell Richey about who Methodists have been and how Asbury made them that way

Russell RicheyFrancis Asbury: Recommended resources

Where should you go to understand Methodists? Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors

the editorsThe accidental revolutionary

In his quest for spiritual peace, Luther had no idea he’d leave his world in turmoil

James M. Kittleson