The accidental revolutionary

AN ADVISER TO SIXTEENTH-CENTURY tourists remarked that people who returned from their travels without having seen Martin Luther and the pope “have seen nothing.” Another man read Luther’s works and declared, “The Church has never seen a greater heretic!” But upon reflection he exclaimed, “He alone is right!”

How could one person evoke such conflicting reactions echoing through the centuries? Luther himself said, “Others before me have contested practice. But to contest doctrine, that is to grab the goose by the neck!” Luther’s childhood gave no indication he would one day split Western Christianity. He was born on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben (about 120 miles southwest of modern Berlin), where both parents may have worked as domestic servants.

Within the year, the family moved to Mansfeld, where his father Hans (spelling his last name Luder) found work in the local copper mines. Hans quickly climbed to ownership or part-ownership of several mines and even became a member of the city council.

Luther remembered his childhood in part for (in today’s terms) its physical abuse. Both his mother and father beat him in frightening ways. He became so estranged from his father on one occasion that Hans sought his forgiveness. But Luther also remembered, “He meant well by me.” Strict physical discipline was normal in the era.

There is also no evidence of anything unusual about the family’s piety. Hans joined others in seeking a special indulgence for the local parish church. Margaretha, Luther’s mother, shared common superstitions. For example, she blamed the death of one of her sons on a neighbor she regarded as a witch.

A farsighted decision

Despite common origins, two things set young Luther apart. First, Hans, who could have satisfied himself with having the lad learn to read, write, and cipher before joining the family business, sent the boy to Latin school at age 14 and then on to the University of Erfurt. Hans was ambitious not just for his son, but also for the entire family. If he succeeded, young Luther would become a lawyer, who, whether in the church or at court, could provide handsomely for both parents and siblings.

Second, Luther proved to be extraordinarily intelligent, earning his bachelor’s at age 19 and his master’s at 22—the shortest time allowed by the University of Erfurt—before proceeding to the faculty of law.

He proved so adept at disputations (public debates that were the principal means of learning and teaching) that he earned the nickname “The Philosopher.” A pleased Hans gave his son the costly gift of the central text for legal studies at the time, the Corpus Juris Civilis.

“Help me, St. Anne”

Unfortunately, the promising law student soon had doubts about the status of his soul and about the career his father had securely set before him. In 1505 the 21-year-old took an officially sanctioned leave from the university and visited his family to seek their advice about his future. On his return, as Luther fought his way through a severe thunderstorm, a bolt of lightning struck the ground near him.

“Help me, St. Anne!” the frightened Luther screamed, hoping to escape the lightning. “I will become a monk!”

Luther spent several weeks discussing his decision with friends. Then, in July 1505, as was required on entering monastic life, he gave away all his possessions—his lute, on which he was proficient; his many books, including the Corpus Juris Civilis; his clothing and eating utensils—and entered the Black Cloister of the Observant Augustinians. As was also customary, he endured more than a month of examining his conscience before proceeding to the novitiate and a further year of scrutiny before becoming a friar.

By all evidence Luther was extraordinarily successful as an Observant Augustinian, just as he had been as a student. He did not simply engage in prayer, fasts, and ascetic practices (including going without sleep, enduring bone-chilling cold, and flagellating himself), he pursued them earnestly.

A priest in less than two years, Luther soon went to Rome as the traveling companion of a senior brother on important business. In addition, his superiors ordered him to undertake the study of theology so he could become one of the order’s teachers.

Though the fears and anxieties that drove him into the Black Cloister had left Luther during his first year or so there, they began to intensify as the novelty of monastic life wore off and he felt increasing terror of the wrath of God. “When it is touched by this passing inundation of the eternal,” he wrote, “the soul feels and drinks nothing but eternal punishment.”

The command to study theology meant he could investigate his struggles intellectually, but it was slow going. His teachers, following the Bible, taught that God demanded absolute righteousness: “Be perfect, even as your Father in heaven is perfect” (Mat. 5:48). People needed to love God absolutely and their neighbors as themselves. When they failed, the church would step in with the grace of the sacraments, and they should repent in a fully contrite manner without the selfish purpose of saving themselves.

But Luther was plagued by the fact that human beings are incapable of the selfless acts and states of mind the Scriptures require. The most crushing one to Luther was this obligation to be contrite and repent. In the late Middle Ages, repentance most commonly occurred in the course of sacramental confession and penance: the sinner confessed, was forgiven, and then performed penitential acts that completed the process.

Luther knew that in the midst of this most crucial act, he was at his most selfish, confessing sins and performing penance out of a human instinct to save his own skin. And yet, sin being sin, he commented later, “If one were to confess his sins in a timely manner, he would have [had] to carry a confessor in his pocket!” As his teachers knew, this fact could lead to despair.

Who could be righteous?

During his early years, whenever Luther came to the famous “Reformation text”—Romans 1:17—his eyes were drawn not to the word faith, but to the word righteous. Who, after all, could “live by faith”? Only those who were already righteous. (See “What did Luther know and when did he know it?,” p. 19.)

The young Luther could not live by faith because he was not righteous—and he knew it. During this turmoil Luther often approached Johannes Staupitz, his superior in the monastic order, about his doubts, sins, and outright hatred of a righteous God. He came so often that Staupitz once commanded him to go and commit a real sin: “You want to be without sin, but you don’t have any real sins anyway . . . the murder of one’s parents, public vices, blasphemy, adultery, and the like. . . . You must not inflate your halting, artificial sins out of proportion!”

But Luther wasn’t comforted: “My conscience would never give me assurance, but I was always doubting and said, ‘You did not perform that correctly. You were not contrite enough. You left that out of your confession.’”

The critical turn in Luther’s life came when Staupitz ordered him to obtain his doctorate and become a professor of the Bible at Wittenberg University. Luther resisted the call, saying, “It will be the death of me!” but finally relented and became a doctor ecclesiae (teacher of the church). There a revolution in his theological thinking occurred in his lecture hall and study from 1513 to 1519.

About late 1513 or early 1514, when he arrived at Psalm 72 in his lectures, he explained to his students, “This is what is called the judgment of God: like the righteousness or strength or wisdom of God, it is that with which we are wise, just, and humble, or by which we are judged.” The last clause is what Luther had read: God judges by his righteousness. But he would teach increasingly that God gives us righteousness. In fact, a little later during these same lectures, he asserted that all the attributes of God—”truth, wisdom, salvation, justice”—are “the things with which he makes us strong, saved, just, wise.”

On the heels of this change came others. Luther no longer understood the church as the institution that boasted apostolic succession, but instead as the community of those who had been given faith. Salvation came no longer by the sacraments as such; instead the sacraments nurtured God-given faith. The idea that human beings had enough spark of goodness to seek out God, commonly taught in the Middle Ages, he proclaimed as coming from “fools” and “pig theologians.”

Humility for him was no longer a virtue that earned grace but a necessary response to the gift of grace. Faith for him no longer consisted of assenting to the church’s teachings but of trusting the promises of God and the merits of Christ. In short, Luther found himself working a revolution that contradicted almost everything he had been taught. It lay there, ready to explode, and even Luther was unaware of how loudly it would do so.

Chain reaction

What happened was more like a long but powerful chain reaction than a sudden explosion. It started on All Saints’ Eve, 1517, when Luther formally objected to the way the short, dumpy Dominican friar Johann Tetzel was preaching a plenary indulgence.

Indulgences were documents individuals bought from the church either for themselves or on behalf of the dead to release either the purchaser or the deceased from purgatory for a certain number of years. A plenary or total indulgence would release a deceased person altogether and was seldom offered. (The first record of a plenary indulgence dates to 1095.)

The money from indulgence sales was used to support church projects, such as, in the case of Tetzel, the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Tetzel carefully orchestrated his appearances to excite public interest, crafting sermons to delight and persuade. (Though he may not have said, “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, a soul out of purgatory springs,” the phrase was certainly a common jingle.)

Luther wanted to question the church’s trafficking in indulgences and challenged all comers to debate the practice in proper academic fashion—his publication of the theses (in Latin) was not an intentional act of rebellion, but simply the accepted way of inviting such a debate.

But the printing press snatched the matter from his hands. His 95 Theses were translated into the common language and spread across Germany within two weeks of printing. Luther was asked to debate the theological issues during the Augustinian order’s regular meeting in spring 1518. He also underwent an excruciating interview with Cardinal Cajetan in Augsburg that fall. It was so painful, as Luther recalled it, that he could not even ride a horse afterward because his bowels ran freely from morning to night from the stress.

Luther had good reason to be anxious. The issue quickly became not indulgences, or even Tetzel’s indulgences (which were extraordinary by any estimate), but the authority of the church: does the pope have the right to issue indulgences? The substance of the original matter was of little concern to Luther’s opponents. In fact, church authorities repeatedly forbade them to debate it with him. The question was instead whether the church could declare that this is so and rightly expect obedience.

The core issue became public at the Leipzig Debate in late June 1519. Students from Wittenberg came armed with staffs. The local bishop tried to forbid the debate, and Duke George of Saxony, who sponsored it, sent an armed guard to keep order. There Luther declared that “a simple layman armed with the Scriptures” was superior to both pope and councils without them. A bull threatening excommunication followed quickly in mid-1520. Luther responded by burning it.

That summer Luther wrote The Address to the Christian Nobility, The Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and On the Freedom of a Christian. With these three essays, he set himself and his (by now) many sympathizers in opposition to nearly all the theology and practice of late medieval Christendom.

In the first he urged secular rulers to take the necessary reform of the church into their own hands (see “The political Luther,” pp. 36–38). In the second he reduced the seven sacraments to three (baptism, the Lord’s Supper, and penance) and radically altered their character. In the third, he told Christians they are free from the law (in particular the laws of the church) even while they are bound in love to their neighbors.

“I will not recant”

The Diet of Worms, held in the spring of 1521, was little more than the backwash from a ship that had already set sail. Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (also King Charles I of Spain, where he lived and ruled) had never been to Germany. He called the Diet to meet the German princes, whom he scarcely knew by name and desperately needed to court. But he knew this friar by the name of Luther also needed to be addressed.

Luther was convinced he would finally get the hearing he had requested four years earlier in 1517. As he was ushered in, Luther was awed to see Emperor Charles V himself, surrounded by his advisers and representatives of Rome; Spanish troops decked out in parade best; electors, bishops, territorial princes, and representatives of great cities. In the midst of this impressive assembly sat a table with a pile of Luther’s books.

The archbishop of Trier asked Luther if he wished to recant his writings in whole or in part. He was taken aback—this was not a debate but a judicial hearing. He begged for time to think: “This touches God and his Word. This affects the salvation of souls.” Given a day in his quarters, he wrote, “So long as Christ is merciful, I will not recant a single jot or tittle.”

The next day’s business at the Diet delayed Luther’s return until evening. Candlelight flickered. He was asked again, “Will you defend these books all together, or do you wish to recant some of what you have said?”

There were three kinds of books in the stack, Luther declared. Some were about the Christian faith and good works, and these he certainly wouldn’t retract. Some attacked the papacy, and to retract these would be to encourage tyranny. Finally, in some he attacked individuals, perhaps too harshly, but those individuals had defended papal tyranny. Surely, the archbishop answered, one individual could not call into doubt the tradition of the entire church: “You must give a simple, clear, and proper answer. . . . Will you recant or not?”

Luther replied, “Unless I can be instructed and convinced with evidence from the Holy Scriptures or with open, clear, and distinct grounds of reasoning . . . then I cannot and will not recant, because it is neither safe nor wise to act against conscience.” Then he may have added, “Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me! Amen.” kidnapped by friends When negotiations over the next few days failed to reach any compromise, Luther was condemned. Still he was granted safe conduct as promised, but only for another 21 days. As Luther and his companions made their way back to Wittenberg, four or five armed horsemen plunged out of the forest, snatched Luther from his wagon, and dragged him off.

His own prince, Elector Frederick the Wise, had abducted him to keep him safe. Luther was now an outlaw; anyone could kill him without fearing reprisals from an imperial court of law. He soon arrived at the Wartburg, one of Frederick’s castles.

Luther despised his enforced stay at the Wartburg. He missed his friends in Wittenberg and hated being sidelined from the action. He even made plans to seek a call to the University of Erfurt where he would be outside his friendly captor’s jurisdiction. That failed, but he did manage to commandeer a horse and make a flying trip to Wittenberg, from which he returned much relieved at the course of events among his friends.

In spite of his complaints, Luther’s 10 months on ice were among the most productive of his life. He continued writing: his touching and almost autobiographical Commentary on the Magnificat, his uncompleted Postillae (homilies on a set of biblical lessons), and his translation of the New Testament into German, of which he did a rough draft within 11 weeks.

But what had begun in a lecture hall was now a popular movement. Throughout Germany monks and nuns were fleeing their monasteries and cloisters—some for conscience’s sake and some for the sake of convenience. Luther felt obliged to respond to people’s practical questions. He took a middle road. How could one best serve one’s neighbor? If one did so in holy orders, then one should remain. On the other hand, if one could serve one’s neighbor better outside the monastery or cloister, then one should live in the world. As his revolution expanded, Luther was increasingly thrust into the public arena. He openly returned to Wittenberg in early spring of 1522 without asking Elector Frederick’s permission. Some argued that all Christians must marry and that all monks and nuns must become laypeople. Luther retook his pulpit and preached on the obligation to love one’s neighbor whatever one’s calling in life.

The hallmark of Luther’s life [as the rest of this issue will illustrate—Editors] was the way he joined forceful personality and forceful doctrine. For him doctrine was never mere scholarship: it was life itself. In his Large Catechism, he urged Christians to read and reread their catechisms, for “in such reading, conversation, and meditation the Holy Spirit is present and bestows ever new and greater light and fervor.” He wanted all Christians to become people taught by God. CH

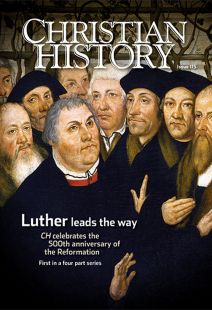

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By James M. Kittleson

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

Dr. James M. Kittelson (1941–2003) was professor emeritus of history at Ohio State University (Columbus), professor of church history and director of the Thrivent Reformation Research Program at Luther Seminary (Minneapolis), and author of Luther the Reformer. A longer version of this article appeared in CH 34.Next articles

Course corrections

300 years before Luther, reformers were already trying to change the church

Patricia Janzen LoewenChrist present everywhere

What bothered opponents most about Luther—from Catholics to fellow Reformers—wasn’t his views on grace but his doctrine of the Eucharist

David C. SteinmetzMomentous vows

Why Luther’s marriage shocked the world and changed visions of family life for centuries to come

Beth Kreitzer