“Contemplate Christ”

One day in 1511, Luther and his monastic mentor, Johannes Staupitz, sat under a pear tree in a garden near their cloister at Wittenberg.

The vicar-general of the Augustinian order told young Luther he should become a professor of theology and a preacher. Luther was taken aback. “It will be the death of me!” he objected. “Quite all right,” said Staupitz. “God has plenty of work for clever men like you to do in heaven!”

Luther did receive his doctor’s degree—just over a year later, on October 18, 1512. That day he also received a woolen beret, a silver ring, two Bibles (one closed, the other open), and a commission to be a “sworn doctor of Holy Scripture.”

He took that commission seriously. It guided his theology and his career as a reformer. Years later he declared, “What I began as a Doctor, I must truly confess to the end of my life. I cannot keep silent or cease to teach.” In his view, the Reformation happened because the pope tried to hinder him from fulfilling his vocation of expounding the Scriptures.

Dying to be a theologian

Though he held a doctor’s degree, Luther was no mere member of a learned guild of scholastic theologians. His theology grew out of his anguished quest for a gracious God. For Luther theology was not simply the academic study of religion. Rather it came out of his reading and thinking during a lifelong process of struggle and temptation.

As Luther never tired of saying, only experience makes a theologian. “I did not learn my theology all at once,” he said, “but I had to search deeper for it, where my temptations took me. … Not understanding, reading, or speculation, but living—nay, dying and being damned—make a theologian.”

Out of Luther’s struggles emerged a theology that shook the foundations of medieval Christendom. Though Luther appreciated the protests made by such forerunners as John Wycliffe of England and Jan Hus of Bohemia, he recognized his own efforts as qualitatively different. (See issues 3 and 68 of CH for more on Wycliffe and Hus.)

Luther’s protest against Tetzel’s sale of indulgences in 1517 did more than call for church reform; it challenged church identity. His radical views were crystallized by later interpreters into three statements on Scripture, faith, and grace that set the stage for reformers to come.

Sola scriptura: Scripture alone

At the Diet of Worms in 1521, Martin Luther declared his conscience captive to the Word of God. But that declaration did not mark his decisive theological break with the Church of Rome. That had happened two years earlier, in July 1519, at Leipzig, nearly two years after the 95 Theses.

Luther’s opponent in the Leipzig debate was an accomplished professor at the University of Ingolstadt, Johann Eck (see “From preachers to popes,” pp. 41–44). An onlooker sympathetic to Luther, humanist scholar Petrus Mosellanus, described Luther at the dramatic face-off:

Martin is of middle stature; his body thin, and so wasted by care and study that nearly all his bones may be counted. He is in the prime of life. His voice is clear and melodious. His learning, and his knowledge of Scripture are so extraordinary that he has nearly every thing at his fingers’ ends. Greek and Hebrew he understands sufficiently well to give his judgment on interpretations. For conversation, he has a rich store of subjects at his command.

Eck, Mosellanus wrote, “has a huge square body, a full strong voice coming from his chest, fit for a tragic actor or a town crier, and more harsh than distinct.” In German Eck means “corner,” and he boxed Luther into one. He forced Luther to say that popes and church councils could err and that the Bible alone could be trusted as an infallible source of Christian faith and teaching.

Under duress Luther articulated what would come to be the formal principle of the Lutheran Reformation: all church teaching must be judged by the Bible. He ended his official statement to Eck, “I am sorry that the learned doctor only dips into the Scripture as the water-spider into the water; nay, that he seems to flee from it as the Devil from the Cross. I prefer, with all deference to the Fathers, the authority of the Scripture, which I herewith recommend to the arbiters of our cause.”

Late medieval theologians, even those who sought reform, placed tradition alongside the Bible as a source of church doctrine (see “Course corrections,” pp. 9–12). The following year, in The Babylonian Captivity of the Church, Luther stated: “What is asserted without the Scriptures or proven revelation may be held as an opinion, but need not be believed.” Luther did not reject tradition outright. He respected the writings of the early church fathers, especially those of Augustine, and he considered universal statements of faith, such as the Nicene and Athanasian Creeds, binding on the church in his day. But he maintained that all creeds, sayings of the fathers, and decisions of church councils must be judged by, never sit in judgment upon, the “sure rule of God’s Word.”

For Luther the church was the creation of the Bible, born in the womb of Scripture. “For who begets his own parent?” Luther asked. “Who first brings forth his own maker?” He held a high view of the inspiration of the Bible, calling it once “the Holy Spirit book.” Arguably Luther’s greatest contribution to the Reformation was his translation of the Bible into German. He wanted common people—the farm boy and the milkmaid—to “feel” the words of Scripture “in the heart.” And what truly distinguished his exegesis was his ability to make the text come alive. For him Bible stories were not distant historical acts but living current events, as we see in his treatment of Gideon: “How difficult it was for [Gideon] to fight the enemy at those odds. If I had been there, I would have messed in my breeches for fright!” For Luther the Bible was no mere depository of doctrine. In it a living God confronts his people.

Sola fide: faith alone

Martin Luther developed his understanding of justification amid both the moralism and the mysticism of late medieval religion (see “Stepping into Luther’s world,” pp. 6–8). He made strenuous efforts to find a gracious God, doing penance according to the dictates of scholastic theology. Ultimately he became frustrated to the point of despair.

Luther’s illumination came at some point during his scholarly labors (see “What did Luther know?,” p. 19). He wrote shortly before his death about the experience:

At last, God being merciful, as I meditated day and night on the relation of the words “the righteousness of God is revealed in it, as it is written, the just shall live by faith,” I began to understand [the] “justice of God” as that by which the just lives by the grace of God, namely faith; and this sentence, “the righteousness of God is revealed,” to refer to a passive righteousness, by which the merciful God justifies us by faith, as it is written, “the just lives by faith.”

This straightaway made me feel as though I had been reborn, and as though I had entered through open gates into paradise itself. From that moment, I saw the whole face of Scripture in a new light. . . . And now, where I had once hated the phrase, “the righteousness of God,” I began to love and extol it as the sweetest of phrases, so that this passage in Paul became the very gate of paradise to me.

Luther considered justification by faith “the summary of all Christian doctrine” and “the article by which the church stands or falls.” In the Schmalkaldic Articles (1537), which could be considered his theological “last will and testament,” he wrote: “Nothing in this article can be given up or compromised, even if heaven and earth and things temporal should be destroyed.”

According to the medieval understanding of justification, which was derived from Augustine, a person gradually receives divine grace, which eventually heals sin’s wounds. But Luther abandoned this medical image of impartation for the legal language of imputation: God accepts Christ’s righteousness, which is alien to our nature, as our own. Though God does not actually remove our sins, God no longer counts them against us. We are at the same time righteous and sinful (“simul justus et peccator,” as Luther put it). Luther called this a “sweet exchange” between Christ and the sinner: “Therefore, my dear brother, learn Christ and him crucified; learn to pray to him despairing of yourself, saying ‘Thou, Lord Jesus, art my righteousness and I am thy sin. Thou hast taken on thyself what thou wast not, and hast given to me what I am not.’”

Medieval theologians considered faith one of the three theological virtues, along with hope and love. They emphasized faith’s cognitive content—intellectual assent to doctrine—and saw that assent as a virtue formed by love.

But to Luther such faith was not sufficient for salvation. (Even demons have it, Paul wrote.) Truly justifying faith—”fiducia,” Luther named it—is something more. It means taking hold of Christ, hearing and claiming God’s promises as we have understood them, and apprehending our acceptance by God in Jesus Christ.

Sola gratia: grace alone

Modern people often see Luther as the apostle of human freedom and the father of rugged individualism. But this view misunderstands his theological revolution, similar to the revolution Copernicus would soon be causing in the scientific realm. Copernicus’s calculations, published in 1543, removed earth—and thus, humanity—from the center of created reality. Likewise, Luther’s theology changed humanity’s place in the process of salvation.

For Luther salvation was anchored in the eternal inscrutable purpose of God. He guarded against human-centeredness by insisting that God’s grace comes from outside ourselves: not just a human possibility, nor a dimension of the religious personality, but a radical and free gift of God, who gives us even the grace to take hold through faith.

“This is the reason why our theology is certain,” Luther explained. “It snatches us away from ourselves and places us outside ourselves, so that we do not depend on our own strength, conscience, experience, person, or works but depend on that which is outside ourselves, that is, on the promise and truth of God, which cannot deceive.”

Luther’s doctrine of the divine sovereignty and initiative in human salvation came to fullest expression in his famous debate with Erasmus over grace, free will, and predestination. For Erasmus, humans, though fallen, remained free to respond to grace and thus cooperate in their salvation (see “The man who yielded to no one,” pp. 46–49).

Luther, however, saw the human will as completely enslaved by sin and Satan: we think we are free, but we only reinforce our bondage by indulging in sin. Grace releases us from this enslaving illusion and leads us into “the glorious liberty of the children of God.” God wants us to love him freely, Luther said. But that is only possible when we have been freed from captivity to Satan and self.

Solo Christo: Christ alone

Luther believed that the study of doctrine can not be divorced from the art of argumentation. He believed foes without and within the Christian church beseige the Gospel and that he needed to set it forth in opposition to competing claims.

Luther felt that each sola faces an enemy: Scripture alone, against Scripture subordinated to a false understanding of tradition; faith alone, against faith achieved by human righteousness; and grace alone, against a theology that humans could merit salvation.

Stated positively, each sola affirms the centrality of Jesus Christ, Christ alone. First, Luther proclaimed that Christ is the sole content of Scripture and the principle for selectivity within Scripture. Famously he criticized the Epistle of James because it did not proclaim Christ sufficiently in his view: “Whatever does not teach Christ is not apostolic, even though St. Peter or St. Paul does the teaching,” he wrote. “Again, whatever preaches Christ would be apostolic even if Judas, Annas, Pilate, and Herod were doing it!”

Secondly, Christ is the center of Luther’s doctrine of justification by faith: through Christ’s substitutionary death on the cross, God acted to redeem fallen humanity. In his Large Catechism, Luther wrote, “We could never come to recognize the Father’s favor and grace were it not for the Lord Christ, who is a mirror of the Father’s heart.”

Finally the doctrine of grace can be approached only through the cross, through the “wounds of Jesus” to which Staupitz had directed the young Luther in his early struggles. Luther’s words to Barbara Lisskirchen, who worried she was not among God’s elect, are words he could have spoken to himself as well:

The highest of all God’s commands is this, that we hold up before our eyes the image of his dear son, our Lord Jesus Christ. Every day he should be the excellent mirror wherein we behold how much God loves us and how well, in his infinite goodness, he has cared for us in that he gave his dear Son for us. … Contemplate Christ given for us. Then, God willing, you will feel better. CH

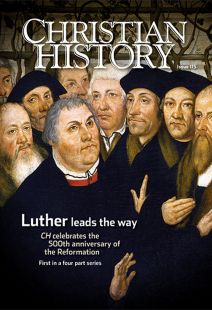

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Timothy George

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

Timothy George is founding dean of Beeson Divinity School in Birmingham, Alabama, and the general editor of the Reformation Commentary on Scripture series. He is the author of over 20 books including Reading Scripture with the Reformers and Theology of the Reformers. This article is adapted from Christian History 34.Next articles

Christ present everywhere

What bothered opponents most about Luther—from Catholics to fellow Reformers—wasn’t his views on grace but his doctrine of the Eucharist

David C. SteinmetzMomentous vows

Why Luther’s marriage shocked the world and changed visions of family life for centuries to come

Beth Kreitzer