Medieval Christianity: Stepping into Luther’s world

THE MEDIEVAL WORLD conjures up all sorts of images, but it’s the unusual ones that stick in our minds: relics in jeweled boxes, religious groups whipping themselves in penance, monks wearing shirts made of hair. Yet we may not recognize how much medieval Europe was a thoroughly Christian culture. To understand Luther, we looked back at this interview from issue 49 about the context in which he arose.

CH: What are some of the greatest misunderstandings modern Christians have about medieval religion?

John Van Engen: First, they assume that Catholicism was a monolithic system, from pope down to individuals, and that it was this way for a thousand years. But from 500 to 1517, European Catholicism underwent enormous changes and periods of centralization and of decentralization.

In a world that had poor transportation, no televisions, and no telephones, the idea of a pope handing out orders that would be obeyed at the local level everywhere—well, that’s something of a dream. When you think about medieval religion, you have to think in regional terms: Catholicism in southern France, in England, in northern Italy, and so on. Though the vast majority of Christians shared the same beliefs and some common forms of worship, there was great diversity.

Second, a great many moderns think medieval religion was mostly about “superstition” and not genuine faith.

CH: Why are such misunderstandings so common?

JVE: Our image of the Middle Ages has been colored by Reformation preaching and teaching. Protestants tended to paint the Catholic Middle Ages in very black terms to justify the kind of radical changes they sought.

In addition, we are heirs of the [eighteenth-century] Enlightenment much more than we realize. The Enlightenment exalted reason and repudiated revelation, faith, religious ritual, and rote learning as ignorant superstitions. That has colored our ability to appreciate medieval religious culture.

CH: Rigorous fasting and self-flagellation seem eccentric. Were they?

JVE: People in the Middle Ages had a strong sense they were to love God not just with their minds but also with their bodies. By disciplining the body and its passions, they believed they disciplined their souls, pleased God, and prepared themselves to receive grace. That’s why we see things like abstaining from sex, praying all night, and walking barefoot several miles to a shrine.

Our sinfulness lies not only in wills but also in passions gone astray. So you have to bring your whole bodily regimen in line with Christ. It isn’t enough to avoid punching your neighbor in the nose, you also have to rid yourself of anger. How do you discipline that? They had this idea that you get at the inner part of you through (a) prayer and confession and (b) disciplining the body. In this way, they would repress or drive out things like lust, gluttony, and greed.

For many people these activities became self-punishments or satisfaction for sin. To Protestants this was a misunderstanding of Christ’s atonement. But there was also that other dimension of discipline.

CH: So if Protestants tried to understand medieval religion, would they identify more with it?

JVE: Yes and no. Yes, because whenever we try to understand another age, we come to appreciate some of its strengths. But no, because there are many features Protestants will still find disturbing. For example, take the cult of the saints. In addition to prayers to the Trinity and to Jesus, medieval people prayed to the saints, and in some instances this moved into outright worship of the saints. Or they would spend more time at a shrine of Mary than at their parish church.

CH: What were the greatest challenges medieval priests faced in teaching people the Christian faith?

JVE: Teaching in an illiterate culture was one; helping people, most of whom did not understand Latin, appreciate the Latin Mass, was another. A third was eradicating superstition. Before Christianity came to Europe, various forms of paganism were all that people knew. By 1100 much of Western Europe was formally converted, but superstition had a way of hanging on.

If you put yourself in the shoes of a medieval person, you can see why. Let’s say your wife’s pregnancy is going poorly. You’re worried both mother and child could die. You pray to Jesus, and more likely, you pray earnestly to Mary, who was thought to look out for women in difficult childbirth. But also in your village, there’s a woman who says, “Whenever we’ve had this problem, we boil certain herbs, lay them on the mother-to-be’s tummy, and say a certain charm—and that really helps.”

People didn’t see this as contrary to their faith. It was like going to the drugstore and getting a little extra help. But priests had to convince people this was unhealthy spiritually.

CH: What are some of the great successes of the medieval church?

JVE: By the sixteenth century, all of Europe (apart from the Jews) was in principle Christian, and many people were devout believers. All this in an area that a thousand years earlier had only a handful of Christians.

In spite of rampant illiteracy, the absence of technology, poor transportation, and stubborn regionalism, there was a commonly shared understanding of how people should live and act. This is particularly amazing because today we assume that to teach moral standards to an entire culture requires strongly centralized government, mass communication, and literacy. But they were able to do this by word of mouth. [For more on how, see CH issue 108 on Charlemagne.—Editors]

CH: What are some legacies the medieval church has left us?

JVE: Cultural legacies abound, like the modern university. The universities of Oxford (in existence sometime before 1096), Paris (1170), Cambridge (1209), and others were all founded in the Middle Ages. The medieval church was anxious to have educated clergy who would in turn educate the laity. There was also a drive to organize knowledge and understand the created universe, and this drive arose directly out of medieval theology. Also, we Christians assume that the culture around us ought to be Christian, which is a medieval worldview. This was not an expectation of the early church, which assumed the world around it would remain mostly hostile to the faith. But in today’s post-Christian era, many Christians are angry and frustrated by an increasingly secular world.

Another medieval assumption is that the death of Christ should be at the center of Christian faith. Westerners forget there are systems of Christianity with other emphases, like the Orthodox concern about the Trinity. The notion that the Christian faith hinges on the suffering and death of Christ is a special contribution of the Western medieval church. When the reformers came along, they changed this theology in certain crucial ways, but they still assumed the central theme is the passion of Christ—not the Trinity or even the Resurrection.

CH: You allude to justification by faith. Was this doctrine forgotten in the Middle Ages?

JVE: Medieval theologians taught that faith is an essential step in being made right with God. But at the popular level, people tended to take faith for granted. They grew up with it. Everybody they knew was Christian. So they concentrated on good works. In addition they listened to the apostle Paul. He talked a great deal not only about faith but also about love, and the end of each of his letters is full of specific admonitions to do good works. So, for the medieval person, the central concern was on making faith manifest in love. CH

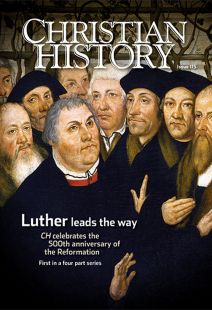

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By John Van Engen

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

John Van Engen is Andrew V. Tackes Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. This interview is adapted from CH issue 49.Next articles

Editor’s note: Luther leads the way

This marks the first of a Reformation series in honor of its fifth centenary

Jennifer Woodruff TaitThe man who painted the Reformation

Lucas Cranach gave us indelible images of the Reformation

Paul Thigpen and the editors