The political Luther

During the Schmalkaldic War, which broke out after Martin Luther’s death, Catholic Spanish troops defeated Protestant German princes and overran much of German Saxony, including Wittenberg. When the Spanish soldiers stood at Luther’s grave in the Castle Church, they demanded that Luther’s body be exhumed and his bones burned as heretic’s bones. But Emperor Charles V stopped them. He is said to have declared: “I do not make war on dead men!”

This story seems to be a golden legend, but it shows the passions Luther aroused. The Reformation was not merely a theological dispute but an event that disturbed all areas of life—social, economic, and political.

Pragmatic Philosopher

Luther formed his ideas not as an abstract political philosopher but as a person in charge of and confronting real-life situations. His correspondence, especially during the last 15 years of his life, shows him constantly involved in political situations, advising and urging city councils concerned with urban reformation, and chastising episcopal and secular princes. Luther took his final journey in the dead of winter in 1546 not for religious reasons but to restore good relations between two territorial princes—brothers who had fallen out over property.

Throughout his life Luther enjoyed the protection and generosity of the electoral Saxon princes. (These noble rulers of Saxony were called “electors” because they were among the seven leaders who had historically elected the German kings.) Frederick the Wise (1486–1525) protected Luther from papal and imperial forces, both because Luther was his subject and because he was the best-known professor at Frederick’s recently founded University of Wittenberg (1502).

Religion played a minor role at best here. Frederick understood little of the “new theology” and cherished his extensive relic collection until he died. He used court chaplain and lawyer Georg Spalatin as a go-between with Luther to avoid compromising himself more than necessary.

However, Frederick’s brother John (ruled 1525–1532) was a convinced reformer, and his son John Frederick (ruled 1532–1547) considered Luther his spiritual father. These cozy relationships have led some to speak of Luther’s Reformation as a “princes’ reformation,” meaning it was primarily a political revolution: local princes asserting their power against Rome under the guise of a theological dispute.

But Luther harshly attacked ecclesiastical princes (bishops and archbishops) in Germany in the early years, criticized secular princes during his later years, and developed a theory of resistance against any rulers who were, in his view, trying to destroy true religion. His polemic against Catholic ruler Georg of Ducal Saxony combined theological arguments with devastating irony and ridicule.

In his letters and sermons, Luther often urged rulers to moderation and equity. In replying to an inquiry in 1528, he wrote, “You ask whether the magistrate may kill false prophets. I am slow in a judgment of blood even when it is deserved. In this matter I am terrified by the example of the papists and the Jews before Christ, for when there was a statute for the killing of false prophets and heretics, in time it came about that only the most saintly and innocent were killed. …I cannot admit [allow] that false teachers are to be put to death. It is enough to banish.”

But he named names when he let loose blasts against actual rulers, contrary to many of his contemporaries. “There are lazy and useless preachers,” he thundered, “who do not denounce the evils of princes and lords, some because they do not even notice them. …Some even fear for their skins and worry that they will lose body and goods for it. They do not stand up and be true to Christ!”

And in regard to politicians, he once said they “are generally the biggest fools and worst scoundrels on earth, but God will find them out, better than anyone else can, as indeed he has done since the beginning of the world.”

Places for Church and State

Luther’s teaching on the priesthood of all believers leveled the clergy to servants of the congregation—not enjoying a higher privilege than the laity, not even in their role as celebrants of baptism and the Lord’s Supper. “Thank God, a child of seven knows what the church is,” he wrote; “the holy believers and the lambs who hear the voice of their Shepherd.” Elsewhere he said it is the “assembly of the saints, i.e., the pious, believing men on earth, which is gathered, preserved, and ruled by the Holy Ghost, and daily increased by means of the sacraments and the Word of God.”

If such views seem commonplace among Protestants today, it is only because Luther made them stick. At the time the church seemed universally arrayed against him, so Luther hoped that lay princes, as baptized Christians in authority, would serve as emergency bishops in reforming the church.

During his Lectures on Romans (1515–1516), Luther commented on Romans 13:1, “Let every person be subject to the governing authorities”:

In our day the secular powers are carrying on their duties more successfully and better than the ecclesiastical rulers are doing. For they are strict in their punishment of thefts and murders, except to the extent that they are corrupted and insidious. …But the ecclesiastical rulers … actually nourish pride, ambitions, prodigality, and contentions rather than punish them (so much so that perhaps it would be safer if the temporal affairs of the clergy were placed under secular power).

Against Rome’s century-long attempt to make the church dominant over the state, Luther argued that God works in the spiritual realm through the Gospel and in the temporal realm through secular authority.

St. Augustine had stressed the negative role of the state (“a great robbery”) as a curb on sin. Luther emphasized the positive. He thought that secular authority serves as the instrument of God’s love, for its laws should conform to the basic natural law, which is the law of love. Luther frequently referred to the ruler as a “father and helper,” “gardener and caretaker,” or “God’s official.” In his view individual rulers were divinely instituted to restrain evil and prevent anarchy and chaos.

Resist Rulers?

Luther taught, however, that there is also a great need for justice in the world and that one has the duty to resist tyrannous rulers who violate natural law and political laws. While every subject should strive to be a good citizen and obey valid laws, he thought that if a regime establishes laws that are contrary to the natural law of love, the regime’s subjects are bound to obey God rather than man (Acts 5:29).

He thought that under such conditions believers should withhold obedience to the government in passive resistance, and, for years, he rejected the idea of active resistance to rulers (except for those he called “healthy heroes” or “wondermen” who, like Samson, found themselves directly and unambiguously called by God to undertake a revolution). He observed that “changing a government is one thing, but improving it is another.”

Luther followed this teaching himself when in 1529–1530 he refused to sanction resistance by Elector John to the emperor. (In the end he yielded only when legal experts convinced him otherwise.) And, in that critical hour when he stood at Worms, Luther resisted the temptation to unleash a popular national uprising against the pope and the emperor. He reminisced many years later, “If I had wanted to start trouble, I could have brought all Germany into a great bloodbath. Yes, I could have begun such a game at Worms that the emperor himself would not have been safe. But what would that have been? A fool’s game! I did nothing but left it all up to the Word.”

Perhaps in his 1534 Commentary on Psalm 101 we see the political Luther most clearly:

The spiritual government or authority should direct the people vertically toward God that they may do right and be saved; just so the secular government should direct the people horizontally toward one another, seeing to it that body, property, honor, wife, child, house, home, and all manner of goods remain in peace and security and are blessed on earth. God wants the government of the world to be a symbol of true salvation and of his kingdom of heaven. CH

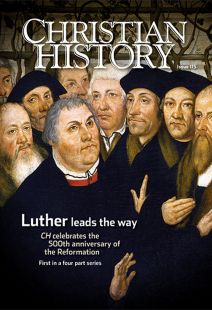

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Lewis W. Spitz

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

Lewis W. Spitz (1922–1999) was William R. Kenan University Professor of History at Stanford University and author of The Protestant Reformation, 1517–1559. A longer version of this article appeared in CH issue 34.Next articles

Editor’s note: Luther leads the way

This marks the first of a Reformation series in honor of its fifth centenary

Jennifer Woodruff TaitThe man who painted the Reformation

Lucas Cranach gave us indelible images of the Reformation

Paul Thigpen and the editorsAfter the revolution

The beginning of the Reformation was not the end of Luther’s troubles

Mark U. Edwards Jr.