Christ present everywhere

WHO WAS JESUS, and what could he have meant to imply about himself when, as the Gospel of Matthew reports, he broke bread and told his disciples to “take, eat, this is my body”? Early Protestants were fairly certain they knew what Jesus did not mean: to suggest that bread and wine had been miraculously “transubstantiated” into his physical body and blood. The word “transubstantiation,” the medieval Catholic understanding of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist, rests on a distinction between the substance of a thing (what it really is) and its accidents (how it appears to observers).

Ever since the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 (see “Course corrections,” pp. 7–10), Catholic teaching had insisted that consecrated bread and wine are transformed by the power of God into the substance of Christ’s body and blood without altering their accidental qualities. Therefore observers could detect no change in the consecrated elements or distinguish them from unconsecrated ones by taste, appearance, weight, or smell.

Like his Catholic opponents, Luther located Christ’s presence in the elements of bread and wine. But he believed transubstantiation is an unsatisfactory explanation of the mystery of Christ’s real presence.

The problem with transubstantiation in Luther’s mind was that it requires the faithful to believe two miracles: (1) that Christ is really present and (2) that his presence requires reducing bread and wine to their accidents. For Luther one miracle sufficed. Christ is substantially present in the Eucharist—but so, too, are the bread and wine. Luther also held that the Eucharist is not a sacrifice. It is not something the priest offers to God for the sins of his congregation—not even when that sacrifice is understood, as medieval Catholics held, as a re-presentation of the unique sacrifice of Christ in an unbloody form. Instead the Eucharist is a gift God gave to the church. Luther preferred to regard it as a “benefit” or “testament” rather than a sacrifice.

Testament was a particularly important word for early Protestants. A testament is a one-sided contract that offers an inheritance to a beneficiary on the death of the testator (the person who makes the contract). A will is one good example.

When Christ the testator died, he fulfilled the condition of his one-sided contract and offered to the church “in his will” the benefits of his death and Resurrection. The church did not in any sense merit such gifts, but received them as an undeserved inheritance. The Eucharist was therefore for the early reformers not a place where sacrifices are offered, but where benefits are received.

Luther agreed with other reformers and disagreed with his Catholic opponents in his contention that the Eucharist is a visible form of the Word of God. That is, he saw it as a proclamation in visible, rather than audible or written, form of Christ’s death and Resurrection. The Eucharist therefore offers Christ, not to God the Father, but to the worshiping congregation. The Word of God, the lively and life-giving voice of the living God, is the instrument by which God created the world and through which he will renew it. That Word is actually the fundamental sacrament of which baptism and the Eucharist are visible forms.

Christ’s presence disputed

There, though, the agreements against Catholicism ended and disagreements between the reformers began to multiply. Luther dismissed his fellow reformer Zwingli’s reading of John 6:63 (“the Spirit gives life; the flesh counts for nothing”), by which Zwingli implied that there is nothing special about the elements. [More about Zwingli to come in CH 118! —Editors]

The “flesh” that God condemns, Luther said, is not the material world, but our self-centeredness that opposes God. Whenever fallen human beings—characterized by Luther as having their hearts turned in on themselves—trust what is not God as God, they commit the primal sin of idolatry, even if what they trust is something as good as human love or as enduring as human friendship.

But, Luther thought, no one commits idolatry by trusting the material channels for grace God has established in baptism and the Eucharist. They are trustworthy because they rest on God’s promise. Not to trust the promise is not to trust God.

Furthermore, the risen Christ is present in the Eucharist. Luther believed that something unprecedented had happened to Jesus’ body in the Resurrection. Although he continued to bear a human body, it was a body no longer subject to limitations of space and time. Indeed the body of the risen Christ could even walk through the door of a locked room to appear suddenly in the midst of his disciples.

Thus Luther thought what had occurred in the Resurrection was a transfer of attributes in which Christ’s human nature took on some of the characteristics of his divine nature—including the trait of ubiquity (the ability to be everywhere). Luther saw no need to bring Christ down from heaven in the Eucharist. Christ is already present on earth because he is still everywhere. He is present in the bread and wine, even before they are consecrated.

Luther once taunted Zwingli with the claim that Christ’s body could be found everywhere, even in a peasant’s bowl of pea soup (though, Luther warned, no one could locate Christ by stirring vigorously). If the risen Christ is where the Father reigns, he is never distant from the worshiping congregation.

Luther drew a simple distinction in German between a thing being present (da) and being accessible (dir da). The risen Christ is present (da) in ordinary bread and wine. But he is accessible to the church (dir da) only in the Eucharist. God has attached his promise to the Eucharist. Only there, and not in ordinary bread and wine, is Christ savingly present in the full reality of both natures, truly human and truly divine.

Luther therefore insisted on a literal reading of the verb “is” in the words of institution (the scriptural narrative of Jesus’ instituting the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, which are said at every Communion service): “This is my body.” The Eucharist is not a mere sign pointing to a distant reality or even an icon through which the power of that distant divine reality is present. It is the thing itself, the true body of Christ present with the bread.

Luther also answered the controversial question of whether unbelievers receive the body and blood of Christ with a resounding yes. The presence of Christ does not depend on the faith of the communicant or the piety of the celebrant but on the reliability of God’s promise. Even if an irrational creature—say, a mouse—were to eat the consecrated host, it would eat the body of Christ.

Nevertheless Luther thought faith is still essential to receive the saving benefits of Christ’s presence. Unbelievers receive the body and blood of Christ, but they eat and drink to their own damnation. Benefits, Luther warned, are restricted to believers.

Who is Jesus? Where can we find him?

Luther believed in and preached what he regarded as the historically reliable narrative of Jesus’ life, death, and Resurrection in the four Gospels, a narrative anticipated in the Old Testament and further explained in the New. Christians are called to obey this Jesus and no other.

At the same time, explaining Jesus as his story is told in the Gospels is no simple task. It compelled Luther and his fellow reformers to use the complex technical language of the ancient creeds. Luther indicated at the beginning of the Schmalkald Articles (a 1537 summary of Lutheran doctrine) that he had no quarrel with Catholicism over the doctrine of the Trinity or the two natures of Christ. Other reformers would have agreed.

But unlike his fellow reformers Zwingli and Calvin, who argued that Christ’s humanity, now ascended into heaven, could not be physically present on earth, Luther saw ample evidence in the New Testament that the risen Christ had undergone a transformation. His body is no longer subject to temporal and spatial limitations.

Therefore it can be physically present whenever the Eucharist is celebrated. The good news for Luther was that Christ is not only present but also accessible. Disagreements over the Eucharist centered on how to grasp Christ on earth. Luther believed that one might not be able to see his presence by vigorously stirring a bowl of pea soup, but the believer would know where to find him when the minister offers the consecrated bread and wine. CH

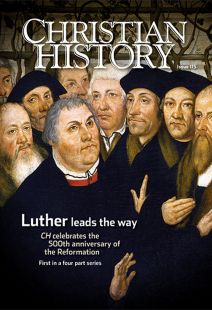

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By David C. Steinmetz

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

David C. Steinmetz is Amos Ragan Kearns Distinguished Professor of the History of Christianity, emeritus, at Duke University. He is the author of numerous books and articles on the Reformation including Luther and Staupitz, Luther in Context, Calvin in Context, and Reformers in the Wings. This article was adapted and reprinted with permission from his book Taking the Long View (Oxford University Press), pp. 115–126.Next articles

Momentous vows

Why Luther’s marriage shocked the world and changed visions of family life for centuries to come

Beth Kreitzer