BONUS ONLINE CONTENT: Recovering the past

Today the word “humanism” often gets a bad rap, used to describe a world without God and often coupled to the word “secular.” But in the 16th century, many humanists were deeply Christian. The imprint they left on the Reformation was a profound one.

Why were humanists called “humanists”? Because they were concerned about what makes us human. In the Middle Ages, scholastic theologians like Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) had argued that what made us human was that we could think: thus, Aquinas compiled a comprehensive, detailed, and precisely argued systematic theology. Humanist and biblical scholar Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) later mocked this approach in The Praise of Folly (1513): “They [the theologians] will explain to you how Christ was formed in the Virgin’s womb … The most ordinary of them can do this. Those more fully initiated explain further … whether ‘the Father hates the Son’ is a possible proposition; whether God can become the substance of a woman, of an ass, of a pumpkin, or of the devil, and whether, if so, a pumpkin could preach a sermon, or work miracles, or be crucified.”

For those like Erasmus who became known as humanists, what makes us human is not precise theological explanations; they were fond of quoting a line from fourteenth-century Italian poet Petrarch, “It is better to will the good than to know the truth.” Instead, what makes us human is that we can talk—and talk beautifully. More than anything else, humanism was a kind of rhetoric—a way of speaking and writing that displayed eloquence, wisdom, and (in the case of Christian humanism) piety.

Humanism arose in the Renaissance, which, broadly speaking, was a movement centered on Italy and focused on a renewed interest in classical antiquity—the great thinkers of Greece and Rome. Renaissance thinkers and artists valued and pursued beauty, learned classical languages, studied ancient philosophy, promoted the dignity of human nature, and emphasized freedom from authority.

“Without Plato,” said the Florentine statesman Lorenzo de' Medici, “it would be hard to be a good Christian or a good citizen.” This statement has been called the manifesto of humanism. Later, Enlightenment thinkers looked back at the humanists as the forerunners of individualism and secularism. But in reality they were very concerned with exactly what Lorenzo said: how to be good Christians.

Modern conservative Christians have the slogan “Back to the Bible;” Erasmus had a similar slogan: Ad fontes, “Back to the sources.” The phrase captures his age's hunger to recover something that had been lost, a golden era before the medieval “Dark Age” muddied the window of vision. If only we were more like ancient Athens or Rome, thought the humanists, our government and our society would not be so corrupt. If only we could learn to make art like the Greeks and Romans did, we could achieve ideal beauty. If only we could study the earliest biblical manuscripts in their original languages, we could understand what Scripture means. If only we could go back to the purer, simpler faith of the early church fathers, we could get closer to God.

The humanists had boundless optimism about human potential (“A man can do all things if he will,” pronounced author Leon Battista Alberti), though they also recognized that free will could cut two ways. In his Oration on the Dignity of Man, Pico della Mirandola wrote that humans may use their unique, God-given freedom to rise to become like angels or sink to the level of beasts.

For the humanists, exalting the beauty of the natural world and the inherent worth of human beings created in the image of God was a way of worshiping God himself. They believed in the ennobling effects of education and the continuity between the wisdom of antiquity and the truth of Christianity. Their delight in Latin and Greek literature extended not just to Plato, Cicero, and Caesar but also to early church fathers like Augustine and Jerome.

Perhaps the most famous of all Christian humanists was Erasmus, often called the “prince of the humanists.” But many spiritual leaders and thinkers of the age were humanists: John Colet (1457–1519), Erasmus’s teacher; English reformer Thomas More (1478-1535); Martin Bucer (1491–1551), who led reform in Strasbourg; Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (c. 1455–1536), nicknamed the “dean of humanists” and a renowned biblical scholar who influenced Calvin; Calvin’s friend Nicolas Cop (c. 1501–1540); and Calvin himself (1509–1564), whose Geneva Academy curriculum emphasized classical languages and the humanities

In their quest for the purity of the past, humanists stressed that Christianity was not a matter of endless ceremonies and rites but an inward affair of faith and individual conscience rooted in the example of Christ. In this and many other ways, they fed the fires of Protestant reform, particularly in northern Europe. Erasmus once wrote, “If you believe in what takes place at the altar but fail to enter into the spiritual meaning of it, God will despise your flabby display of religion.”

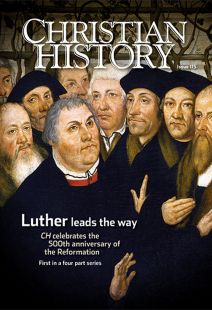

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Jennifer Trafton and Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

Jennifer Trafton was managing editor of Christian History and Biography from 2005-2008 and is a children’s book author, creative writing teacher, and artist. Parts of this article are adapted from her article “Painting the Town Holy” in our issue 91 on Michelangelo. Jennifer Woodruff Tait is the current managing editor of Christian History.Next articles

BONUS ONLINE CONTENT: Covenant children

Infant baptism in the Reformation

Jennifer Woodruff Tait and John OyerChristian History timeline: Downloadable Reformation timeline

Christian History's Reformation timeline

the editors