Self-serving vice or society-building virtue?

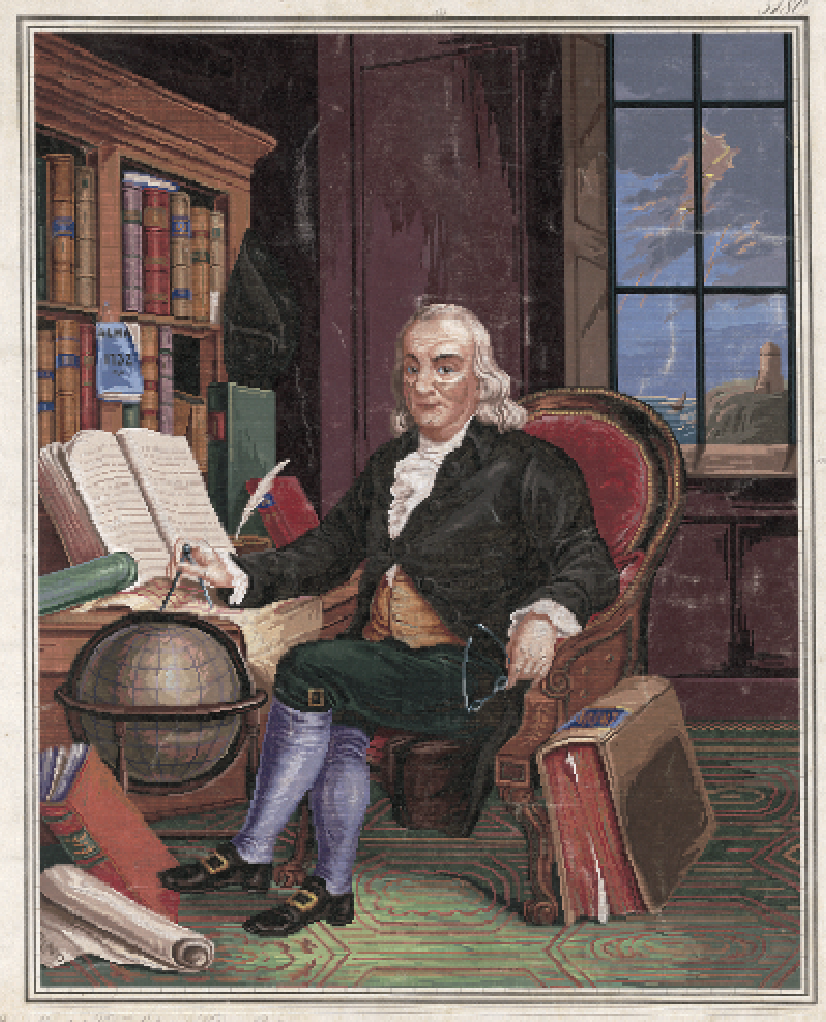

[Benjamin Franklin, Embroidery Pattern, 1842 to 1852—Popular Graphic Arts / [Public domain] Wikimedia]

When I was in high school, I fell in love with the girl next door, the eldest daughter of unassuming people living in a modest home in an unpretentious part of town. They quietly supported the local school district and the public library, but their names were rarely found in the newspaper. Imagine my surprise when one day I found out her father was probably the richest man in town! He owned the largest commercial seafood business of its kind in the world and also the local commercial bank. They were what my mother called “filthy rich.”

I knew these were not ill-gotten gains, but I also couldn’t understand. I had been brought up in a home where my father had to work several jobs just to maintain a middle-class lifestyle. Surely people so rich would have owned the grandest house in town, driven the flashiest cars, worn the most expensive jewelry, sent their children to the finest private schools, and traveled the world. Yet they did none of those things. Instead they lived a modest lifestyle, reinvesting wealth for future generations and filling their time with small, anonymous acts of kindness and generosity, without any fanfare or expectation of return.

Controversial ethic

It wasn’t until many years later when I began to study theology and political economy that the penny dropped for me. My former girlfriend came from a strict Dutch Reformed household, and their lifestyle exemplified something called the “Protestant Ethic” in action. And it was far more controversial than I had realized.

The term is taken from the English title of pioneering German sociologist Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905). Weber (1864–1920) was the son of middle-class Prussian parents; his father was a civil servant, and both intellectual stimulation and estrangement between his parents characterized his home. He became professor of economics at the University of Heidelberg, but, after resigning due to mental illness, entered the relatively new field of sociology as editor of the journal Archives for Social Science and Social Welfare.

In his groundbreaking book, Weber sought to explain why some countries (particularly in northern Europe and the United States) were so much more successful in generating wealth than other capitalist countries. Others had tried to explain this in strictly technical terms. Some believed it simply manifested Karl Marx’s theory of worker exploitation. According to Marx (1818–1883), the bourgeoisie (middle class) would wring ever-greater wealth from the collective brow of the working class until the system ultimately collapsed under its own weight. Weber did not find this explanation satisfactory; while he agreed with Marx on many issues relating to the social ills of nineteenth-century Europe, he never subscribed to his economic theory.

Others believed that this success resulted from a natural evolution that in time would benefit all capitalist economies. Again Weber was unconvinced. Still others suggested it was merely the result of technological advancement, combined with relatively easy access to capital and a laissez-faire (“let it be”) attitude toward free markets—what we call today “neo-liberal” economics. But this combination of factors was not unique to the countries in question and had indeed been a hallmark of capitalism since Adam Smith (see p. 27).

Weber believed something else must be at work, some other constellation of motivating factors. He set out to find what that constellation entailed.

-------------------------------------------

The “Protestant Ethic” includes:

1. a regimented organization of one’s life

2. a belief that one is called by God to a particular vocation that must be executed with religious zeal; one’s work is one’s worship (Rom. 12:1)

3. a “this-worldly” asceticism: self-discipline in secular callings

4. the presence of religious organizations transmitting this ethos over generations

5. an aversion to personal pleasure through conspicuous consumption

6. a desire to “prove” one’s state of grace via the fruits of one’s labor

------------------------------------------

Overwhelming Protestants

Weber’s hunch was based upon a simple observation suggested at the very beginning of his book: “For any country in which several religions coexist . . . people who own capital . . . tend to be, with striking frequency, overwhelmingly Protestant.” He set out to see if this was true—and, if so, why.

While the countries of northern Europe presented considerable evidence for this theory, their cultures and economies still exhibited remnants of previous eras—the enduring influence of Catholicism and the feudal system, and the legacy of guilds and mercantilism (see p. 34). For Weber the relatively pristine nature of the American model, steeped in the Puritanism of its founders and the deeply held religious beliefs of its people, represented a set of “ideal types” he could observe and dissect.

On his one and only visit to the United States in 1904, Weber was struck, not only by the economic efficiency of the American system, but also by the well-ordered social structures that seemed to undergird it. He noted that religion was still widely practiced and that upstanding business people were expected to support local churches and charities and align their nonreligious activities with their religious beliefs.

America of course was not officially Calvinist, but its leaders and many of its people had been highly influenced by Calvinist thought, especially during its formative years. During the eighteenth century, as Enlightenment ideals began to generate a mood of independence, a wave of religious fervor had also gripped the colonies; evangelists such as George Whitfield and Jonathan Edwards ushered in what has become known as the First Great Awakening. They called on individuals to reject formulaic practices of established churches in favor of a deeply personal and direct relationship with God. Furthermore, believers were told that if they were truly saved, this would be manifest in lives of pious obedience and in God’s subsequent blessing.

Weber identified this thinking as a significant “psychological motivator” for wealth accumulation. It was woven into the fabric of American consciousness in various forms, but especially in the writings of highly influential founding father Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790). Franklin’s aptly entitled Necessary Hints for Those That Would Be Rich (1736) contains pithy expressions that became part of American vocabulary: “time is money,” “money begets money,” and “a good paymaster is lord of another man’s purse.” For Franklin it was a person’s moral duty to make as much money as possible—as an expression of piety, not as a means for social climbing or even for personal pleasure. Weber wrote:

Benjamin Franklin himself, although he was a colorless deist, answers in his autobiography with a quotation from the Bible, which his strict Calvinistic father drummed into him again and again in his youth: “Seest thou a man diligent in his business? He shall stand before kings” (Prov. xxii. 29).

Weber asserted that wealth creation as a virtue became the “spirit” of American capitalism, resulting in believers remaining in this world and making money while also practicing great self-discipline regarding that money. Motivated by a desire to prove their state of grace and believing that obedience to their individual calling is a religious duty, they stoked the economic engine of capitalism with religious zeal, resulting in economic success unlike anywhere else in the world.

Future warnings

For several reasons Weber’s thesis has been criticized both in theory and practice. First, Weber overestimated the psychological motivation of wealth creation as a marker of salvation. Weber’s view on this was probably conditioned more by his own troubled boyhood home than by a genuine understanding of Reformed theology. His book demonstrates very little firsthand knowledge of theology at all.

Second, the socioreligious structures that evolved to support this ethos seemed at best exclusive and at worst cultic. For many years Roman Catholics, Jews, and others were regularly excluded from the social and economic circles creating much of America’s wealth. Titans of industry formed a very exclusive “club”; their exclusivity was copied throughout the country.

Yet many still think that Weber’s basic observations are correct, even commendable. Surely people of faith should align their religious beliefs and economic ethics, and various theologians have taught that nothing is wrong with wealth creation done for virtuous reasons and in a virtuous manner (see pp. 13, 35, 37). The danger, however, is when economic efficiency becomes divorced from moral standards, with wealth subsequently created in unethical ways and for purely selfish ends. Weber himself warned against just such a phenomenon, and recent history has proven him to be quite prophetic. CH

By Kenneth J. Barnes

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #137 in 2020]

Kenneth J. Barnes is Mockler-Phillips Professor of Workplace Theology and Business Ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and author of Light from the Dreaming Spires and Redeeming Capitalism.Next articles

Christian History timeline: Market matters

Some ways Christians have preached, thought about, shaped, critiqued, and participated in economic life throughout church history

The editorsBringing profit to neighbors

The church and economic theories from zero-sum to mutual benefit

Jordan J. Ballor