Songs, battle cries, and sonnets

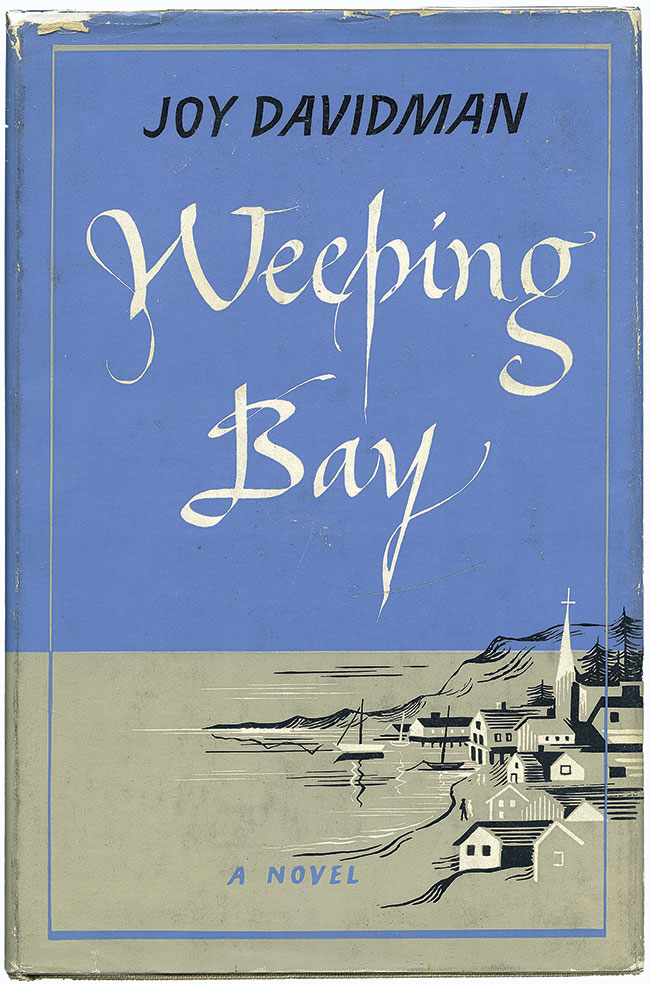

[Joy Davidman, Weeping Bay, 1950. Used by permission of the Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL]

Joy Davidman’s literary career, like her life, was regrettably short but astonishingly full. Early poems and stories appeared in the Hunter College Echo, her school’s literary magazine on which she served as coassociate editor, followed by periodicals including Poetry and New Masses, a magazine tied to the Communist Party.

If Davidman is remembered today for anything other than her marriage to Lewis, it is typically for her Spanish Civil War poetry, the best of which launched her into the red-hot spotlight of New York City’s literary left. In 1938 she submitted a manuscript of primarily political verse—Letter to a Comrade—to the prestigious Yale Younger Poets competition; Pulitzer Prize–winner Stephen Vincent Benét named her that year’s recipient. The award came with publication by Dial Press and a glowing foreword by Benét hailing Davidman as the voice of a generation.

Shortly thereafter, supported by her talent, drive, and new credentials, Davidman began working for New Masses as an editor, book reviewer, and film critic. She bolstered her film critic role with experience from an unsuccessful six-month stint in Hollywood in 1939 as a junior screenwriter for MGM.

The following year Davidman published her first novel, Anya (1940), a Russian peasant story based in part on tales of the old country passed down by her mother. It features a young and sensual protagonist who bears a striking resemblance to Anya’s author. Critics received the book favorably. However, they panned her second novel, Weeping Bay (1950), about life on the Gaspé Peninsula, citing the rambling and disorganized prose and the many underdeveloped characters.

A world at war

As a critic writing essays, Davidman was truly at her best: brilliant, widely read, incisive, witty. Her name appeared on the New Masses masthead through April of 1946, though she contributed infrequently and rarely attended staff meetings following the birth of her first child, David, in March of 1944. Before David’s arrival Davidman had spearheaded and edited an anti-Fascist anthology called War Poems of the United Nations: The Songs and Battle Cries of a World at War (1943), selecting and translating verse from 150 poets representing some 20 countries. (When she didn’t receive enough submissions from countries crucial to represent, like England, she wrote contributions herself under pseudonyms, accompanied by fictitious bios.)

After leaving the Communist Party-USA and converting to Christianity, Davidman wrote much but published little. Her love sonnets to Lewis were published decades after her death as A Naked Tree: Love Sonnets to C. S. Lewis and Other Poems (2015), edited by Don W. King, who also compiled a collection of her letters, Out of My Bone: The Letters of Joy Davidman (2009).

Other letters remain unpublished, including many Davidman wrote to her younger brother, Howard (these remain in a private family collection), and a crucial series written to Bill Gresham in 1952 and early 1953, chronicling her momentous first trip to England and her evolving relationship with Dianetics. The Wade Center has archived those letters along with numerous unpublished poems, short stories, and novellas.

The last book Davidman saw to print in her lifetime was Smoke on the Mountain: An Interpretation of the Ten Commandments, a Lewis-inspired theological book (in fact, he helped her hone some of her ideas). Smoke on the Mountain grew out of a series of articles published in Presbyterian Life magazine in 1953 that Davidman wrote about the Decalogue from her perspective as a Jewish convert to Christianity.

“In a sense the converted Jew is the only normal human being in the world,” Lewis wrote in his foreword to the British edition of Smoke on the Mountain: “. . . we christened gentiles, are after all the graft, the wild vine, possessing ‘joys not promised to our birth’.” In Davidman’s writing he saw that “the Jewish fierceness, being here also modern and feminine, can be very quiet; the paw looked as if it were velveted, till we felt the scratch.”

By Abigail Santamaria

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #140 in 2021]

Next articles

“At our level”

Lewis was a loving correspondent, godfather, and friend to the children in his life

Joe RickeQuestions for reflection: Jack at home

Questions to help you think more deeply about this issue.

the editorsJack at home: recommended resources

With scores of books by and about C. S. Lewis—where to begin? Here are suggestions compiled by our editors, contributors, and the Wade Center.

the editors