The forgotten Inkling

THE GRACIOUS ENGLISH BOOKSTORE CLERK had not heard of Owen Barfield. His early, groundbreaking work of literary criticism, Poetic Diction, didn’t ring any bells. Nor did his masterpiece, Saving the Appearances. I didn’t mention his children’s fantasy, The Silver Trumpet, or his whimsical autobiographical novel, This Ever Diverse Pair, dividing the two sides of his life into two separate individuals—stolid lawyer Burden and creative dreamer Burgeon. Instead I hazarded: “He was a friend of C. S. Lewis.” Her face lit up. “Oh! Was he an Inkling?”

second friend and maker of myth

Barfield was not only an Inkling, but arguably one of the Inklings who most formed Lewis’s thought. For years before his conversion, Lewis had prided himself on his rationality, his resistance to the lure of myth and the supernatural. Such things were nice in poetry, and poetry was one of his greatest pleasures, but he thought they were, as he remarked to Tolkien early in their friendship, “lies breathed through silver.” But in a fateful conversation on Addison’s Walk, Tolkien convinced Lewis that myth connects human beings to divine truth—a memory, however corrupted, of the union with God that we had before the fall.

But Tolkien was not alone in pushing Lewis toward a more robust understanding of the imagination. Lewis met Owen Barfield in 1919 while they were fellow undergraduates at Oxford. He later wrote of him in Surprised by Joy: “The Second Friend is the man who disagrees with you about everything. . . . Of course he shares your interests; otherwise he would not become your friend at all. But he has approached them all at a different angle. He has read all the right books but has got the wrong thing out of every one. . . . You go at it, hammer and tongs, far into the night . . . or walking through fine country that neither gives a glance to, each learning the weight of the other’s punches, and often more like mutually respectful enemies than friends.”

During most of the 1920s, while living near Oxford, Barfield worked on Poetic Diction (1928), his first major book. There he argued that poetry recalls an earlier stage in human linguistic development when ideas were bound up with the words that conveyed them. For instance, in ancient Hebrew the word ruach could mean “breath,” “wind,” or “spirit.” Barfield believed that ancient people would not have distinguished these as different possible meanings, but would have experienced them as one unified thing. Words used in poetry unite the levels of meaning that we normally keep apart in “prosaic” modern speech.

In the early 1920s, Barfield also encountered the thought of Austrian philosopher and mystic Rudolf Steiner, founder of a movement known as “anthroposophy” which believes that humans had once intuitively known the spiritual world. By 1924 he was a full-fledged member of the Anthroposophical Society. (This was one of the things he and Lewis fought about as they walked over English hills and dales.) Barfield came to see a connection between Steiner’s concepts and his own conclusions about the unity between literal and metaphorical language in ancient poetry. Fellow friend and former Oxford classmate Cecil Harwood embraced the movement as well.

“silly medievals”

Lewis was, at the time, still an atheist and horrified by the fact that two good friends believed what he regarded as a silly “medieval” superstition, with “gods, spirits, afterlife and pre-existence, initiates, occult knowledge, meditation.”

But Lewis also respected Barfield’s and Harwood’s intellects and moral characters. Furthermore, he respected Barfield as an intellectual foil. During the 1920s they engaged in what Lewis called the “Great War”—a philosophical debate wherein Lewis defended “absolute idealism,” a philosophy popular at that period in Britain although shortly to fall out of favor. According to it, one absolute Reality consists of all experience. Our limited experience of ourselves as separate is illusory. We are, objectively, part of the one Reality, but we don’t have direct access to it: no personal relationships, with God or anyone else.

Lewis was terrified by the possibility of delusion and insanity inherent in a claim to have had direct supernatural experiences. He did not object to the idea that the imagination catches a glimpse of ultimate Reality, but he insisted that this glimpse can’t be expressed in words. On the one hand, Lewis saw the Absolute, which can only be perceived briefly through mystical experience. On the other he saw everyday material reality. The terms of the one can never be used to describe the other.

But Barfield rejected this dichotomy—and indeed all dichotomies. He believed that imagination not only perceives truth but actually creates it: our very experiences of the physical world result from the mind’s interaction with spiritual reality. Thus we do not give “meaning” to an objective outside world. Meaning is truth.

In addition to arguing for the imagination, Barfield also argued for the past’s wisdom. Lewis noted after his conversion that he began the “Great War” under the influence of “chronological snobbery,” regarding past ages as inferior. Barfield, according to Lewis, cured him of this superior attitude.

Barfield later wondered if he had done the job too thoroughly, criticizing Lewis’s often uncritical praise of the past in his mature work. Barfield believed that truth is an interaction between our minds and whatever is “outside” or “beyond” our minds; thus he believed it changes and grows.

One of Lewis’s later works, The Discarded Image, a loving and detailed examination of the medieval model of the universe, bears witness to what Lewis had learned from Barfield. Yet at the end, Lewis qualified his admiration by saying that, no matter how much the medieval model might delight us as it delighted our ancestors, “it was not true.” The dichotomy Barfield had sought to overcome in the Great War was still there: delight is one thing, truth another.

How far Lewis’s orthodox Christianity led him to remain cold to some of Barfield’s odder ideas is not clear. Lewis, in one of his relatively rare comments on anthroposophy after his conversion, said that his primary concern was that anthroposophists do not really believe in “God the Father Almighty.” Barfield, for his part, accused Lewis of stressing the Father over the Son. Barfield believed in the Trinity, but he interpreted it in terms that often sounded more like impersonal forces than a traditional Christian understanding.

who changed whom?

After his conversion, Lewis refused to continue his debate with Barfield about the nature of knowledge, much to Barfield’s frustration. But Lewis’s later writings show an appreciation of Barfield’s insights on what is wrong with treating the physical world as a “dead thing.” The Abolition of Man (Barfield’s favorite among Lewis’s writings) takes aim at the division between “objective” and “subjective” that leads people to say that only physical things are real, while beauty and truth and moral values are purely “subjective.” Lewis even, in that book, expressed a good word for Steiner. And in Surprised by Joy he said of his lifelong Second Friend: “I think he changed me a good deal more than I him.”

Lewis’s later fiction is often seen as evidence that he gave the imagination a greater role: the magnificent Narnian Chronicles as well as the Space Trilogy and Till We Have Faces. But in Barfield’s opinion, there always remained a fundamental difference between them. He characterized Lewis’s position as being like a Victorian man who put women on a pedestal of idealized romantic love, not wanting them “sullied” by contact with mundane reality. “Lewis was in love with the imagination,” Barfield said. “But I wanted to marry it.” Deeply influenced by Romantic poetry of the early nineteenth century, Barfield embraced anthroposophy because it seemed, in his words, “Romanticism come of age.” In particular he identified with Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s belief that true imagination is creative—bringing new meaning into existence.

In Saving the Appearances (1957) Barfield argued that everything we know, including physical objects such as trees, comes from a collaboration between our senses and external reality. Color, shape, size, texture—all of these things depend on our senses. There is no “green” apart from eyes that can perceive color. Scientists describe physical reality in terms of atoms and particles. But this isn’t what we experience when we see or hear or touch a tree.

According to Barfield ancient people lived in a state of “original participation,” conscious that the things they perceived have a life of their own—something “on the other side” of the tree communicating with them. In the modern world, however, people experience the world outside themselves as a world of dead “things.” Both Greek philosophy and the Old Testament encouraged this, but the real turn to separation, for Barfield, began with the Protestant Reformation and the scientific revolution. Together they created a material world no longer filled with spiritual forces, but rather with things that can be understood, quantified, and controlled.

But it was also a world where the divine Logos had become incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth, profoundly changing the nature of human history and beginning a new kind of participation. Through Jesus, human beings can participate in reality in a more conscious, individual way. As Barfield saw it, we now face the task of growing into the new kind of participation made possible by Jesus—one in which the heart and mind are fired by the light of Christ. This requires not only moral transformation but also a new way of looking at the world; one in which the imagination plays a central role.

Lawyer and philosopher

Saving the Appearances was one of the few books Barfield managed to write during the three decades when he worked as a lawyer in his family’s London firm. After his 1960s retirement, he became more active as a writer and enjoyed increasing fame (particularly in the United States) and a growing reputation as a philosopher who challenged modern materialism and offered creative answers.

In many ways Tolkien, though never personally as close to Barfield as Lewis, reflected Barfield’s insights most fully. Barfield theorized about the imagination a great deal, but his own fiction was often stilted and didactic.

As a philologist (scholar of language), Tolkien took an interest in Barfield’s theories in Poetic Diction. He once told Lewis that Barfield’s ideas had permanently altered how he taught the history of language. And the sense so many have that Tolkien’s imagined world is real gives substance to Barfield’s claims about the imagination’s creative role.

Much of Tolkien’s writing works from hints, usually linguistic, creating some kind of puzzle requiring explanation. For instance, Anglo-Saxon has a lot of words implying horse-centered culture, even though historical Anglo-Saxons fought mostly on foot. From these hints came the entire culture of Rohan in The Lord of the Rings. Using precisely the kind of complex metaphors that Barfield studied in Poetic Diction, Tolkien created a world often seeming more real than the “real world.” Even the archaic language for which Tolkien was criticized serves, according to Barfield’s theories, to create a “gap” between the story and the prosaic associations modern readers bring to the text.

Tolkien reintroduced heroic literature to the modern world, as his legion of imitators demonstrates. Hooded black riders, dark lords in dark towers, cheerful and naive heroes of small stature, mysterious elves who live in forests—these things have passed into the consciousness of the modern world. To some degree Tolkien changed how we see the world, and by doing so changed the world; insofar as Barfield helped to shape Tolkien’s work, this may be Barfield’s most lasting legacy. But if Barfield’s understanding of our challenges has any validity, we need a legion of Tolkiens and Lewises to reshape reality by the fire of their imaginations.

So Lewis recognized when he dedicated The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe to Barfield’s daughter, Lucy: “I wrote this story for you, but when I began it I had not realized that girls grow quicker than books. As a result you are already too old for fairy tales, and by the time it is printed and bound you will be older still. But some day you will be old enough to start reading fairy tales again.” All seven sages would have agreed that when the world grows old enough, the fairy tales need to be waiting. CH

By Edwin Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Edwin Woodruff Tait is a contributing editor at Christian History. Portions of this article appeared in CH issue 78.Next articles

A Christian revolutionary?

Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957) proclaimed Christ as Lord over areas from theater to economics

Suzanne Bray“We still make by the law in which we were made”

Tolkien and “subcreation” — the making of a secondary, fictional world

Colin DuriezFriends, warriors, sages

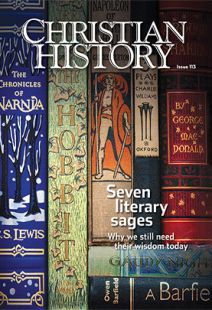

How seven writers gave us stories that endure, imparting truths that never fade

the editors with Alister McGrath, Chrystal Downing, Colin Duriez