The national spirit

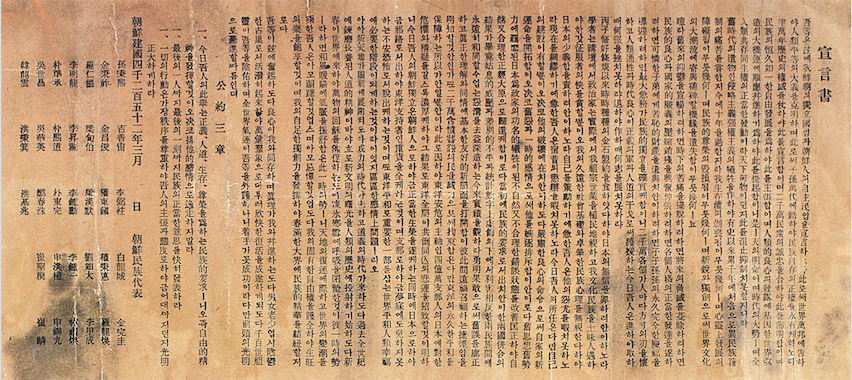

[The Proclamation of Korean Independence. March 3, 1919— 33嬣 / [Public domain] Wikimedia]

Unlike many of its Southeast Asian neighbors, Korea escaped Western control; although exploited, it was never colonized. Perhaps that is why this Asian nation was uniquely open to Western faith when political upheaval struck. Not long after Protestants arrived in Korea, Japan invaded and annexed it. Many Christians influenced the resulting Korean movement for independence, including Horace G. Underwood (1859–1916), the first ordained Protestant missionary to Korea, and Sun Chu Kil (1869–1935), one of the first ordained Korean ministers.

Underwood was known for evangelistic zeal; as a seminarian his nickname was “roaring Methodist,” and in Korea he was called “a Methodist preacher in the Presbyterian mission.” Staid medical missionary Horace Allen (1858–1932) accused him of “bawling hymns in a Ch’emulpo hotel” and “instructing natives and teaching them his songs.” Underwood compiled the first Korean hymnbook, chaired a Bible translation committee, helped found the Korean Religious Tract Society and the Seoul YMCA, and served as a professor in the Presbyterian Theological Seminary (PTS) for years.

Officially Protestant missionaries remained politically neutral. Nevertheless Underwood’s founding of the Ch’ongdong Church in Seoul in 1887 involved Korean Christians in an electoral process of church government. He had the mission adopt a “self-support” policy: leadership roles were to be taken by Korean nationals, and each Christian was to “live [for] Christ in his own neighborhood, supporting himself by his trade.” He also helped found what is now Yonsei University, a cooperative venture between Presbyterians and Methodists, which taught Korean language and history; the number of Korean professors increased year by year, and Yonsei nursed the birth of the national spirit.

Father of the Korean church

By contrast Kil was raised a Taoist and a Confucian. In 1897 literature from Christian missionaries touched him, and he “wet his table with his tears, thinking of his evil ways.” Then he heard a flute and a voice calling Kil Sun Chu! Surprised, he prayed, “My beloved God, forgive my great sins and save me.”

In 1903 Kil entered PTS; one of its first graduates, he pastored the Central Presbyterian Church of Pyeng Yang and founded “day-break” prayer meetings, which became a prominent feature of the Korean church. People called him “the father of the Korean church” and one of its “brightest ornaments and greatest men.” Kil was also a patriot. Until the Japanese forbade it, he taught Unmun (the native script) in night schools at his church; he also used Korean music in worship, played by a prominent traditional musician. This resulted in a hymnal revision containing five hymns sung to native Korean melodies.

After the Russo-Japanese War ended in 1905, the Japanese took over most Korean government. In 1907 they forced the king to abdicate and disbanded his army. That year national revival began, fostered by Kil’s preaching and teaching. Many disillusioned independence fighters joined the church and found there a mobilizing power that would ultimately infuse the 1919 March First Independence Movement.

Kil actively worked for independence—distributing flags, preaching Christianity as a Korean religion, and counseling nonviolence—and was one of 33 signers of the 1919 Declaration of Independence. As a consequence the Japanese imprisoned him. The March First Movement was crushed; a Korean Provisional Government in exile was formed by Methodist Syngman Rhee (1875–1965). Korea’s independence would not come until 1945, with Rhee its first president in 1948. By then Christianity was so tied to independence that many Koreans did not see it as imposed by a foreign colonial power.

By In Soo Kim

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #141 in 2021]

In Soo Kim, professor of historical theology at the Presbyterian Theological Seminary in America and author of Protestants and the Formation of Modern Korean Nationalism, 1885–1920, from which this is excerpted with permissionNext articles

Representative of the outcast

Josephine Butler’s civic engagement helped improve the lives of Victorian women

Jane RobinsonBrave medical and theological sister

As doctor, activist, and ultimately theologian, Katharine Bushnell sought to improve women’s lives

Kristin Kobes Du MezThe needs of the worker

Working-class civic engagement helped catalyze the rise of the Social Gospel

Heath W. CarterPreaching and practicing

Fathers and sons shaping the common good—sometimes very differently

Aaron Griffith