The sacred duty

Q: What do cornflakes, peanut butter, veggie burgers, and probiotic soy milk have in common?

A: You can thank Seventh-day Adventists for all of them.

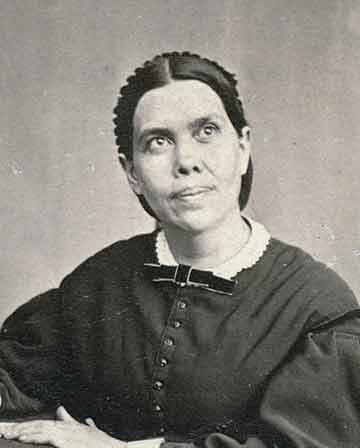

In 1863, less than three weeks after the Seventh-day Adventist Church was officially organized, its designated prophet had a 45-minute vision about health. Ellen White’s (1827–1915) own health was not great; her husband James’s was worse; and many Adventist pioneers were breaking down from overwork and careless habits.

It was time, she told the movement’s leaders, to start practicing the laws of health established in Eden. Most Adventists had already given up alcohol and tobacco. They now needed to reject coffee and tea, rich desserts, white bread, and meat.

For White, health reform went way beyond the practical necessity of keeping the fledgling church’s 3,500 members alive. Living healthfully, she insisted, was a “sacred duty.” As bearers of God’s image and temples of the Holy Spirit, Christians should take the best possible care of their bodies. In a 1909 sermon, she reaffirmed her vision of 46 years earlier:

[God] instructed me that those who are keeping his commandments must be brought into sacred relation to himself, and that by temperance in eating and drinking they must keep mind and body in the most favorable condition for service.

Food habits, however, resist change, and White’s ideal diet—especially her recommendation to subsist on fruits, vegetables, and grains—did not appeal to everyone. Some Adventists did indeed give up all meat; others argued that only pork was harmful; still others banned any foods deemed “unclean” in Leviticus. White herself did not go completely vegetarian for another 30 years. By then some Adventists were advocating a vegan diet (she called them “extremists”).

soy milk, anyone?

If White started her church down the path of healthy eating, her protégé John Harvey Kellogg (1852–1943) marketed health reform to the rest of the world (see “What would Jesus buy?,” pp. 36–39). The Whites persuaded young Kellogg, a self-taught printer’s assistant, to go to medical school. In 1876 the newly minted doctor, now 24, was appointed director of the Battle Creek Sanitarium. The health resort, featuring such cures as colonic irrigation followed by probiotic yogurt flushes, soon became trendy among the elite: the guest list was said to include such household names as Henry Ford, Mary Todd Lincoln, Sojourner Truth, J. C. Penney, and Warren G. Harding.

Following White’s lead, Kellogg promoted a vegetarian diet heavy on whole grains, nuts, and fiber. To enhance the sanitarium’s menu, he set up a food lab and developed peanut butter, soy milk, granola, imitation meats, and his trademark cornflakes.

Kellogg eventually left the church, but Adventists did not abandon his diet. In 1906 the church set up a health-food company near a Southern California sanitarium. In 1939 an Adventist doctor started a second near one in Ohio. By the 1960s those two companies—Loma Linda and Worthington—were the largest fake meat producers in the United States.

Today the Seventh-day Adventist Church counts some 20 million members worldwide. Many are vegetarian; most avoid alcohol, tobacco, and “unclean” meats. Whatever one thinks of Adventist theology, in Southern California, at least, Adventists live an average of 10 years longer than their neighbors.

By LaVonne Neff

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #125 in 2018]

LaVonne Neff, freelance author and blogger at LivelyDust, raised as an AdventistNext articles

Food in Christian history: Recommended resources

Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you understand the story of food and faith.

the editors