BONUS ONLINE CONTENT: The unlucky cardinal

NO FIGURE in the English reformation lost more and was less deserving of the losses which he suffered than Reginald Pole. Though a cousin of the king, he was forced to spend most of his adult life in exile because of Henry’s ill will toward him--always fearful, while Henry lived, of the long arm of the king’s vengeance. While the Catholic church showered on him the honors which his native country had denied him, he saw the theological positions which he defended rejected at Trent, his hope for election to the papacy thwarted by one vote, and his orthodoxy questioned by Pope Paul IV. Even when shortly before his death he returned to aid Queen Mary in reclaiming England for the Catholic faith, he watched his valiant efforts for reform come at last to nothing.

Pole was born on March 3, 1500, in Stourton Castle, Staffordshire, to Margaret of Salisbury, the niece of King Edward IV, and Sir Richard Pole, a cousin of Henry VII. With Tudor and Plantagenet ancestry, Reginald Pole was related to the royal houses of both Lancaster and York. Indeed, Catherine of Aragon, the first wife of Henry VIII, always cherished the hope that her daughter, Mary, and Pole might be united in marriage in order to strengthen the Tudor claim to the throne.

Pole was tutored in Greek by William Latimer and then sent away to school, first at the Carthusian Monastery of Sheen and later at Magdalen College, Oxford. Through Latimer, Pole was introduced to Christian humanism, a movement of reform which attempted to link the Christian present with the humane values of classical and Christian antiquity. The voice of Christian humanism, however, tended to be drowned out by the controversies which dominated England in the sixteenth century. The controversy over royal supremacy and then over the issues of doctrinal and liturgical change, and not the more moderate reform of morals and of education envisioned by the humanists, stirred the passions of Pole’s contemporaries and claimed their loyalties.

From 1519 to 1527 Pole, with the financial support of Henry VIII, continued his education on the continent, studying at Rome, Padua, and Venice. The years spent at Padua were decisive for Pole. There he met and became fast friends with Pietro Bembo, Gasparo Contarini, and Jacopo Sadoleto, men known not only for the breadth of their learning but also for the genuineness of their concern for reform.

The king’s matter, but not Pole’s

In 1527 Pole was recalled to England by Henry, who was quietly trying to find a way out of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Pole wanted no part of the divorce proceedings against Catherine and retired to the monastery at Sheen on the pretext of taking up again the studies which had been interrupted by his recall to England. He left England for Paris, with Henry’s permission, to study theology and to disengage himself from the “King’s Great Matter.” He was followed, however, by Henry’s appointment of him as ambassador to the court of Francis I and by Henry’s command that he take part in a special mission to the University of Paris. Henry wanted Pole to convince the faculty at Paris to support Henry in his contention that his marriage to Catherine was invalid. Pole protested that he lacked the skill and experience for such a commission. Paris did finally support Henry, but only, as Pole had rightly feared, by the slimmest of margins.

When Henry summoned Pole to return to England in 1530, there was every reason to believe that the king intended to confer new honors on his younger cousin. Cardinal Wolsey had fallen and left empty the sees of Winchester and of York. The king needed an ally to offset the influence of Bishop John Fisher, whose persistent opposition to the divorce threatened its success. Pole could have either Winchester or York, if he would only swallow his principles and throw his wholehearted support to Henry. But Henry had misjudged his man. In a stormy interview in the king’s private drawing room Pole refused the tempting bribe which Henry dangled before him. By defying Henry, Pole lost the favor of the king and very nearly lost his life as well.

In 1532 Pole received the grudging permission of the king to leave England and return to Italy. Two years later Parliament passed the First Succession Act, which validated Henry’s secret marriage to Anne Boleyn, and the Act of Supremacy, which acknowledged Henry to be the supreme head of the church in England. Once again Henry needed an ally to support his cause in the face of the opposition which his radical policy had evoked. And once again he turned to Pole.

In 1535 Thomas Starkey, who had served as Pole’s chaplain on an earlier visit to Italy and who was now the chaplain to the king, relayed to Pole by letter the king’s plea for his support. Pole did not immediately reply to Henry. Indeed, it was not until Pole heard of the execution of Bishop Fisher and Sir Thomas More that he felt impelled to enter the public controversy against Henry. From September 4, 1535 to March 30, 1536, he was absorbed in writing his reply to the king, De Unitate, a classic defense of the doctrine of papal supremacy and an impassioned attack on Henry’s schismatic policy.

Henry was outraged by what he regarded as Pole’s stubborn opposition to his wishes and vented his anger on Pole’s family in England. He ordered the immediate execution of Pole’s brother and the imprisonment of his mother, Margaret of Salisbury, who later--also by Henry’s order--was beheaded in the Tower of London. The break between Henry and Pole was final. Had Pole dared to face down the king’s wrath and return to England Henry would have seized and executed him on the spot. As it was, he lived in constant fear of Henry’s hired assassins.

Serving the pope

While Pole’s defense of the papacy had earned the undying hatred of the king of England, it had also merited the admiration of the Vatican. Pole was called to Rome, where he was made a cardinal by Pope Paul III and employed by the Roman curia. When twenty thousand men in Lincolnshire rebelled against Henry in 1536 in the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace, Pole was named papal legate to England. The pope believed that Pole, with his extensive family connections in England, was the proper man to take maximum advantage of Henry’s temporary embarrassment. By the time Pole reached Paris, however, the rebellion had already been crushed.

Pole’s later attempt in 1537 to unite Francis I and Charles V in an alliance dedicated to the invasion of England and the reduction of Henry to obedience to the Roman church also ended in failure. Pole had been associated from the very first with the reform party in Rome which supported the colloquy at Regensburg between Protestants and Catholics. By the summer of 1541 it had become clear that the discussions at Regensburg had failed to produce the hoped-for reunion with the dissident Protestants. Indeed, the discussions had had precisely the reverse effect. They had shown to moderates of both sides how wide the chasm between Rome and Wittenberg had grown. Furthermore, the cause of Protestantism was prospering. The evangelical movement had crossed the Alps into Italy and was daily growing in strength in the duchy of Milan. Evangelical groups had even been uncovered at Modena and Lucca. The penetration of Protestantism into the Latin nations of Christendom had begun.

Pole and two other papal legates arrived in Trent for the beginning of the Council of Trent on November 21, 1542. But poor attendance forced the council to be suspended in July 1543 (Pole had already been called back to Rome.) After further delays, it eventually opened in December 1545; Pole was again a legate. At nine-thirty in the morning on December 13, 1545, the procession formed in the Church of the Most Holy Trinity. The hymn, Veni, Creator Spiritus, was chanted, and the procession began. Approximately four hundred bishops filed into the cathedral and took their places. Cardinal Cornelio Masso preached; the Mass of the Holy Ghost was celebrated; the papal bull, Laetare Jerusalem, was read. By two o’clock in the afternoon the service was over.

The second session of the Council of Trent was held on January 7, 1546. The opening address, though it was delivered by Angelus Mascarelli, had in fact been written by Cardinal Pole. The address was a stirring summons to the Catholic church to repent and reform itself. Rather than allowing the council to choose the easy path of recrimination against the Protestants, Pole urged it to examine its own life and to acknowledge the guilt of its own sins:

“We exhort you!…We are all in the same boat!…In the midst of tempests and dangers we must arouse ourselves and be vigilant lest we crash on the rocks.… Strong in faith and hope, let us direct our voyage, so we may arrive at the port of salvation for the glory of God.… Before the tribunal of God, we ourselves are guilty.…Truly we the shepherds are the cause of the evils now oppressing the Church. If anyone thinks this is an exaggeration…facts themselves which cannot lie, bear witness to the truth of these words.…How will the Holy Spirit guide us if we do not admit that our shameful faults merit the just judgment of God?… With our prayers and a humble voice and contrite heart let us invoke the Holy Spirit to illumine our hearts.…We exhort you, with love in the Lord, with one heart and spirit to glorify God the Father in Christ Jesus, Who is God the Blessed, for ever, Amen!”

In 1548, at the end of the tenth session, Pole withdrew as papal legate to Trent. By that time the council had rejected not only Luther’s understanding of justification, which was to be expected, but also the more moderate doctrine of double justification defended by Girolamo Seripando. Though the motives for Pole’s withdrawal from Trent are still in dispute—he pled health at the time—there is good reason to believe that he left in part because of his dissatisfaction with the conciliar decree on justification. Not that Pole was a heretic! On the contrary, he submitted to the teaching of the Catholic Church and resisted any temptation to break with it.

Pope Paul died on November 10, 1549. Pole, along with his rival Carafa, was a leading contender for the papal crown and came within one vote of election. A delegation of imperial cardinals approached Pole and offered to give him the chair of Peter by acclamation. Pole refused their offer and insisted that he would only accept the papacy if he were elected to it by proper canonical procedure. The next day, however, he fell five votes short of the number needed for his election.

Back home again

In 1553 Mary Tudor fell heir to the throne of England. Unlike her half-brother Edward VI, Mary was a Catholic, who proposed to restore the Roman Catholic system and papal supremacy set aside by her father. Pole was appointed in 1554 to serve as Mary’s adviser and (once again) papal legate to England. When Cranmer was executed by Mary for his part in the divorce proceedings against her mother, Pole succeeded him as the archbishop of Canterbury and the primate of all England. Immediately he set about to enforce in the English realm the reform measures taken by the Council of Trent. He recommended the establishment of seminaries—a word he coined—for the proper training of priests.

In the last analysis it was Pole’s allies and not his enemies who undercut his work. Mary launched, against Pole’s advice, a policy of severe repression against the Protestants. The privy council and Parliament went along with the queen because they had only expected a few heretics to be burned. They were taken aback when over two hundred and fifty perished in the flames. In spite of Pole’s attempt to reform the Catholic church in England and not simply to reinstate it, Mary’s persecutions and her unpopular Spanish marriage undid much of his work before it could take root. The Roman Catholic church became identified in the minds of many Englishmen with bigotry, blood, and Spain.

In terms of cold logic, the Marian persecutions were a disastrous mistake. They not only turned people against the Catholic church; they also drove into exile the moderate Protestant leaders. Many of the young men who left England as lukewarm Protestants returned at Mary’s death as fiery Calvinists. Ironically, Mary became, not the restorer of the Catholic past, but the mother of English Puritanism.

As if it were not enough that Pole saw his work undone by the excessive zeal of the queen, he had to contend as well with the jealousy of his old rival, Carafa, who had been elected as Pope Paul IV. The pope accused Pole of heresy to the queen and proposed to revoke his legatine status. His move was delayed by Mary, who argued that Pole’s continued presence in England was essential for the program of Catholic reform and restoration. However, before the matter could be brought to a successful conclusion, death intervened. On November 17, 1558, Mary passed away. A few hours later on the same day, her cousin followed her.

No man loved England, that other Eden, more than Pole. And yet he lost her twice, once to Henry’s wrath and then to Mary’s piety. With the death of Mary, England fell to the Protestant daughter of Anne Boleyn. Pole, who thought he was the first of a new line of Roman Catholic archbishops of Canterbury, proved instead to be the last.

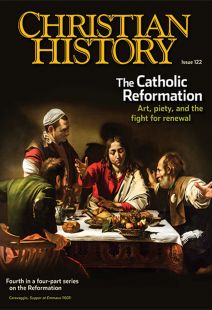

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By David C. Steinmetz

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #122 in 2017]

David C. Steinmetz (1936-2015) was Amos Regan Kearns Distinguished Professor Emeritus of the History of Christianity at Duke Divinity School. This is adapted from his book Reformers in the Wings (Oxford, 2001), 38-46. Used by permission.Next articles

BONUS ONLINE CONTENT: This is my body, argued for you

How do we meet Jesus in the Eucharist? Everybody in the 16th century seemed to have a different idea

David C. SteinmetzBONUS ONLINE CONTENT: Recovering the past

Christian humanists believed in continuity between classical wisdom and Christian truth

Jennifer Trafton and Jennifer Woodruff TaitBONUS ONLINE CONTENT: Covenant children

Infant baptism in the Reformation

Jennifer Woodruff Tait and John OyerChristian History timeline: Downloadable Reformation timeline

Christian History's Reformation timeline

the editors