Understanding God through light and tides

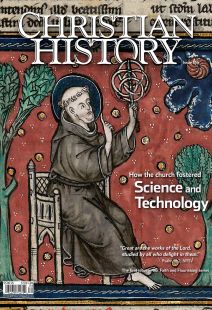

[Works of Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln, 15th C. England; Royal 6 E. V, f.6; British Library Board 05/05/2020]

And God said, ‘let there be light.’ And there was light.” In chapter 1 of Genesis, this verse signals the first day of the creation of the world. Aptly enough this sentence also begins the natural philosopher Robert Grosseteste’s (1175–1253) treatment of the first day of creation in his theological masterwork from the 1230s, the Hexameron. Taken from the Greek, Hexameron means “six days,” and the term refers to a genre of commentary writing that dates back to the fourth century. Basil of Caesarea, Augustine, and—much later—the Venerable Bede all wrote such commentaries, and Ambrose produced one in Latin that was an adaptation of Basil’s Greek work.

Grosseteste followed the conventions of this ancient tradition, but he also brought to bear the fruits of his lifelong study of nature. This included detailed descriptions of such phenomena as planetary motion, the tidal periods of the sea, and, of course, light and vision. After all, as he reminded his readers, the light described in Genesis “is understood . . . to be physical light.”

Grosseteste was able to fortify his interpretation of the Scriptures with a deep knowledge of nature thanks to the many years he had spent as a student, and then a master, at the nascent universities of western Europe. Born to a family of modest means in Suffolk, England, he received an early education in the arts, law, and medicine before beginning his career as a master at Oxford sometime around 1200.

He interrupted his teaching at Oxford to study theology at the University of Paris from 1209 to 1214. Upon his return, he became the chancellor of Oxford University (1214–1230), and five years later was elected bishop of Lincoln; he served in that position until his death. A prolific author on many subjects, he penned a treatise on Christian law and translated (with commentary) Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics.

Experiment and cause

All the while Grosseteste pursued with interest recent translations of Greek and Arabic works on the natural sciences; soon he began to write treatises on these subjects himself. In 1221 he explored the causes of sound. Five years later he finished a study on the effects of the moon’s motion on the periodic movements of the tides. And from 1232 to 1235, before starting the Hexameron, he busied himself with a treatise on mathematics and three treatises on light: on color, the sun, and the rainbow. In the third he employed the law of refraction to explain a rainbow’s shape and its position in relation to the observer.

Grosseteste’s conclusions were not always right according to the findings of modern science (for instance, though his account of the rainbow employs the law of refraction, it is incorrect). Nevertheless his work was highly influential and continues to interest historians, in part because he applied a systematic method in his studies. Building on but going beyond ancient Greek mathematics and logic, he called his method “analysis and synthesis.” Through it he sought to resolve or analyze the effects of nature back to their initial conditions.

Grosseteste instructed his readers to begin with an experience (experientia) and to work backward from it to find its causes. Scholars continue to debate the extent to which Grosseteste’s method anticipated the later scientific standard of hypothesis-driven experimentation. What remains clear is his own commitment to using this method to better understand the order of the cosmos—the relationship between God the final cause and his creation.

By Nicholas Jacobson

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #134 in 2020]

Nicholas Jacobson, postdoctoral fellow in the history of science, medicine, and technology, Observatoire de ParisNext articles

Christian History Timeline: Faith and Science

A few of the highlights of Christian exploration of science that we touch on in this issue

the editorsThe clergy behind science as we know it

Enlightenment-era pastors didn’t oppose modern science. They helped advance it.

Jennifer Powell McNutt