Where the gates of splendor led

JIM ELLIOT, Nate Saint, Pete Fleming, Ed McCully, and Roger Youderian are known collectively as the Auca Martyrs. But what if the story of Operation Auca were placed in an entirely different context?

In this scenario, a single mother contacts her young minister. Her 16-year-old son is very troubled, refusing to go to school and making violent threats against visitors. The minister offers to come to the house and share the gospel with the boy. When he arrives, the woman unlocks the door, the minister enters, two shots are fired, and the minister is dead. The son later testifies that he feared that the man entering his house was going to kill him.

Is the minister a martyr? Truly this was a terrible tragedy. But was the minister’s visit foolhardy, and was he killed because of his Christian faith?

Beginning with Stephen in the book of Acts, Christianity (like other religions) has witnessed untold numbers of martyrs—those slain because they were preaching, or refusing to deny, the faith. For example, on February 5, 1597, more than two dozen Christians were crucified in Nagasaki and remembered since as the Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan. In the decades that followed, some 6,000 Japanese believers who refused to deny their faith were hunted down, tortured, and killed. Others renounced their faith and lived.

Five young missionaries

Like the minister, the five young missionaries ventured into an area that was unsafe and were killed by people who feared them. The ultimate aim of the missionaries, like the minister, was to bring the gospel message, though in neither case were they killed for that reason. Indeed, the native people had no concept of outsiders entering their territory to peacefully bring them a message of salvation.

Many other missionaries have died of disease in tropical climates. Their deaths, like those of explorers, merchants, and other travelers, however, were indiscriminate. They made a great sacrifice to serve in dangerous, disease-ridden areas, but should they be considered martyrs?

The five missionaries who died in Ecuador in 1956 (as had some Shell Oil Company workers years earlier) were killed by spear-throwing Auca warriors defending their territorial lands. The very name Auca—meaning “savage,” as in “fierce, bloodthirsty savage”— was a contemptuous term bestowed by surrounding Quichuas. Their actual tribal name, as the missionary widows would later learn, was Huaorini. But the missionaries knew them as Aucas—savages with a reputation

for murder.

Operation Auca was not sanctioned by a mission organization. None of the agencies that sponsored the missionaries would have signed off on it. It was simply too risky. For that reason the plan was strictly confidential—almost conspiratorial. The missionaries were tight-lipped and communicated in code only. The mission, in the words of Nate Saint, was “high adventure, as unreal as any successful novel.” After his death, his story was told by Russell Hitt in Jungle Pilot and more recently by his son Steve Saint in End of the Spear.

The most familiar account of the massacre, however, was associated with Jim Elliot. His widow, Elisabeth, wrote the best-selling Through Gates of Splendor (1957), still in print. It is appropriate to identify Elliot as the leader of the venture. Although pilot Saint located the tribe in September of 1955, he advised caution in moving ahead. “The reason for the urgency,” he wrote “is the [Plymouth] Brethren boys [Eliot and McCully] feel that it is time now to move.” Pete Fleming, also Plymouth Brethren, was more hesitant. But Elliot was described as “chewing the bit.”

Why did Elliot’s haste trump Saint’s caution? Above all else, Elliot feared delay would threaten secrecy. If their mission boards got wind of what was going on, the plan would be scrapped in a heartbeat. Or Saint’s sister Rachel Saint would find out and tell her supervisors at nearby Wycliffe, who might quickly mobilize a team and beat the men to the punch.

High drama

But there were other reasons for the haste. The plan truly was high drama, an enticing adventure that brought diversion from tedious, day-to-day work in the hot, steamy jungle. The men worked among relatively peaceful Quichuas who were part of a vast network of native tribes. But not surprisingly the Quichuas seemed less than eager to learn to read or to study difficult religious concepts. Progress was interminably slow for the energetic and enthusiastic young men.

Roger Youdarian, with his wife, Barbara, was the most recent arrival in Ecuador, but was already disappointed. A paratrooper in World War II, he told his diary he was miserable and ready to call it quits: “There is no ministry for me among the Jivaros or the Spanish. . . . I wouldn’t support a missionary such as I know myself to be, and I’m not going to ask anyone else to. Three years is long enough to learn a lesson and learn it well. . . . The failure is mine. . . . This is my personal ‘Waterloo’ as a missionary.”

After initial contact with the Aucas in the fall of 1955 through Saint’s ingenious bucket drop (where goods were sent down via a bucket on a rope), final plans quickly took shape. Although Saint had cautioned that each advance should be allowed to “soak in” before additional steps were taken, in less than three months after sighting the settlement, he was regularly ferrying the men into Auca territory by plane to communicate via bucket and loudspeaker. Initially the endeavor included only four men. That changed in late December, as Pete Fleming’s diary shows: “It was decided that perhaps I ought to prepare to go on the expedition in order to gain by numbers more relative security for all.” He planned to return to safety each night, however, by flying out with Saint.

The real drama began in the early morning hours of January 3, 1956. Saint, a highly skilled pilot—daredevil, some said—landed his bright yellow Piper Cruiser for the first time on the narrow sandy beach of the Curaray River. Throughout the day he took off and landed, each time bringing more supplies, while those on the ground hastily built a tree house. Then he and Fleming flew out for the night.

Except for a visit from two native women and one man, the next days were uneventful. But on Sunday, January 8, as Saint and Fleming were returning to the encampment, they spotted a sizable contingent of Aucas on the trail. Saint radioed his wife, Marj, with a lighthearted message: “Looks like they’ll be here for the early afternoon service.” He promised to make contact with her again at 4:30. He never did. All five men were speared to death.

Two years later, in 1958, Rachel Saint and Elisabeth Elliot and her daughter walked to the settlement with Dayuma, a woman who had grown up in the tribe and now acted as a link. Two white women and a little girl led by a long-lost tribal member did not pose a threat to the fierce warriors. Saint and Dayuma stayed for decades, giving their lives to language learning and evangelism.

As a result of the tragedy, many people were challenged to commit their lives to missionary service, and countless individuals were transformed in other ways. I am one of those. In the late seventies at a small Bible institute, I was asked to teach the history of missions; the professor bowing out of the course commented that it was an important topic, but it was too bad the subject matter was so boring.

For anyone teaching by the book, his words rang true. Mission texts were filled with facts and figures: centuries of worldwide mission endeavors, thousands of missionaries sponsored by hundreds of mission agencies in scores of countries around the world. How could I possibly teach this course?

Giving and gaining

Then I picked up Through Gates of Splendor. I was left with more questions than answers, but no book had a more profound impact on my life. My course became a biographical history of missions, which led to a book on the topic, followed by decades of teaching and writing in the field of missions. I cannot imagine where I would be today were it not for that book inspired by the deaths of the five missionaries.

Jim Elliot is perhaps most remembered by an oft-quoted line in his journal: “He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain that which he cannot lose.” Elisabeth Elliot, however, was not always so sure. During a difficult time in her own mission work before she married Jim, she wondered: “Had I come here, leaving so much behind, on a fool’s errand?”

The question is valid for all risktakers. Was the secretive and speedy contact with the Aucas a fool’s errand? Were the warriors killers or defenders of their lands and dear ones? And are the five missionaries correctly considered martyrs? Elisabeth Elliot’s reflections some 30 years later do not necessarily answer these questions, but they do offer insight:

For those who saw it as a great Christian martyr story, the outcome was beautifully predictable. All puzzles would be solved. God would vindicate Himself. Aucas would be converted and we could all “feel good” about our faith. . . . The truth is that not by any means did all subsequent events work out as hoped. . . . There were arguments and misunderstandings and a few really terrible things, along with the answers to prayer. CH

By Ruth A. Tucker

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #109 in 2014]

Ruth A. Tucker is the author of over 20 books, including From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya: A Biographical History of Christian Missions.Next articles

The Jerusalem of the East

When the guard’s flashlight beam swung away and the dog’s barking ceased, Professor Cho had a revelation: Like most North Koreans, he had forgotten God. But God had never forgotten North Korea

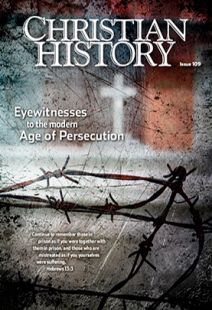

Hyun Sook FoleyEyewitnesses to modern persecution, Did you know?

Christians have suffered for their faith throughout history; here are some of their stories.

The editorsEditor's note: Modern persecution

What you will read in this issue is, in part, history that is still being written

Jennifer Woodruff Tait