Erasmus Laid Down His Pen and Went Home to Christ

“O JESUS CHRIST, Son of God, have mercy upon me! I will sing of the mercy of God and of His judgment.” With those words, Erasmus breathed his last on this day, 12 July 1536. He was sixty-nine.

His life had been full of sorrows, adversity, and threats mingled with success, adulation, and fame. He was born out of wedlock. His father, led to believe that the boy’s mother was dead, took monastic vows and only discovered the truth too late. Both parents died when Erasmus was young. By beatings, starvation, and false promises of leisure to engage in literary pursuits, Erasmus was coerced into entering the priesthood. Cruel schools starved him and exposed him to serious illness, which left him prematurely old-looking.

At that time, the state of education was poor. Erasmus soon developed a passion to raise its standards: “I did my best to deliver the rising generation from this slough of ignorance, and to inspire them with a taste for better studies,” he wrote after he was famous.

Erasmus owed his popular fame to his book the Praise of Folly. A satire, it poked fun at the abuses of his day, such as the sale of indulgences and praying to Mary. Kings and even popes did not escape his mockery: “Whatever of toil and drudgery belongs to their office, that they assign over to St. Peter, or St. Paul, who have time enough to mind it; but if there be any thing of pleasure and grandeur, that they assume to themselves, as being hereunto called.”

This and other books awakened a desire for reform in the church. Later generations would say that Erasmus loaded the cannon and Luther fired it. Unfortunately, Erasmus found himself attacked by both sides. Lutherans turned against him because he would not join their cause, which he considered destructive to the church. Catholics threatened his life and banned some of his books because they blamed him for starting the Reformation.

More than just a man of wit, Erasmus was also a great scholar. He mastered Latin and Greek, the languages of learning in his day, and issued New Testaments in both. His Latin version corrected a number of errors in the church’s official translation. Much of his life was spent translating Greek works into Latin, especially those of the Eastern church fathers, so Western Christians could read these works for themselves.

Above all, he wanted people to know the Bible better, and had no use for philosophical subtleties—pagan or Christian. “What is at the back of all this glorification of Cicero? I will answer in one or two words, whispered into your ears. It is a mere cloak for paganism, the revival of which is more to them than the glory of our Lord.”

Shortly before his death he wrote, “My life has been long if measured by years. Take from it the time lost in struggling against disease, it has not been so very long after all. You talk of the great name I shall leave behind me, and which posterity is never to let die. Very kind and friendly on your part, but I care nothing for fame and nothing for posterity. I desire only to go home and find favor with Christ.”

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

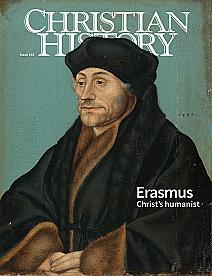

Erasmus's story is told in full in Christian History #145, Erasmus, Christ's humanist

Never miss an issue of Christian History. Subscribe today.