Mr. Chesterton Made His Confession

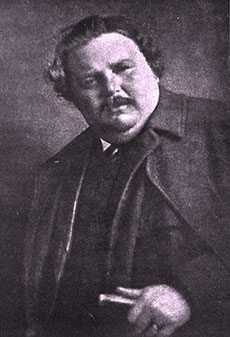

[ABOVE: G. K. Chesterton—Edwin E. Slosson, Six Major Prophets. Boston, 1917. Public domain]

ON SUNDAY, 30 July 1922, a huge and famous man took a special walk to church. If people knew nothing else about G. K. Chesterton, they probably knew that he was immense, notoriously absent-minded, and a defender of Roman Catholicism. Chesterton sported all three attributes plainly that day as all four hundred pounds of him lumbered into a Catholic church to make his first confession. While looking for his prayer book moments before the service, he pulled out a thriller instead.

Asked why he joined the Catholic Church, Chesterton replied, “To get rid of my sins.” He went on to add that sin confessed and adequately repented is abolished, and the sinner begins again as if he had never sinned. That same day, he wrote a poem that began:

“After one moment when I bowed my head

And the whole world turned over and came upright…”

and concluded

“The sages have a hundred maps to give

That trace their crawling cosmos like a tree,

They rattle reason out through many a sieve

That stores the sand and lets the gold go free:

And all these things are less than dust to me

Because my name is Lazarus and I live.”

It was not inevitable that Chesterton become a Catholic. In fact, he had been raised a liberal. Although his parents had him baptized in the Anglican Church, they were at best Unitarians in practice. Chesterton himself flirted with atheism. Attending art school, he followed skepticism to its limit, solipsism (belief that one’s own thoughts are all that verifiably exists) and also dabbled in spiritualism. He soon realized that madness lay down those paths. Watching a friend disintegrate through sensuality, he realized he had no heart for atheism. Shortly afterward, he left art school, became a journalist, and rose to fame with his criticism of the Boer War.

Chesterton wielded one of the most powerful pens of his day. His fiercest attacks were against the idea of inevitable progress, which caused him to clash with writers such as George Bernard Shaw, of whom he wrote: “He started from points of view which no one else was clever enough to discover and he is at last discovering points of view which no one else was ever stupid enough to forget.”

Poems, essays, criticism, novels, and mystery stories flowed in a seemingly endless stream from his pen. The distinguishing marks of Chesterton’s writings were vivid imagery and strong doses of paradox. “Paradox,” he said, “is truth standing on her head to attract attention.” Sometimes his paradoxes skewered things widely thought to be true, while other times, he championed ideas widely thought to be false. His wit made his paradoxes especially memorable: “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult; and left untried,” and “The English statesman is bribed not to be bribed.”

As Chesterton worked out what he believed, he became more conservative in his thinking. Following an attack by Robert Blatchford on Christianity, Chesterton came out against him on the side of the Christian faith and thereafter increasingly defended Christianity and the Catholic Church. It was no surprise when he finally overcame his own mental resistance and asked to be received into communion with Rome. His friend Father John O’Connor, the inspiration for Father Brown in Chesterton’s detective stories, presided over the ceremony in a hotel dance room (with a tin roof) that served as the Catholic Church near his home in Beaconsfield. Later Chesterton helped establish St. Teresa’s church there, where his grave and that of his wife Frances can be seen today.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

G. K. Chesterton is one of the British writers featured in Christian History #113, Seven Literary Sages.

Christian History #75, G. K.Chesterton, is devoted entirely to him

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Other Events on this Day

- CHRISTIAN FREDERICK SCHWARTZ DID THE WORK OF THREE MEN IN INDIA

- A Trio of Martyr Saints Miraculously DISCOVERED in Bisceglie