A key in the Master’s hand

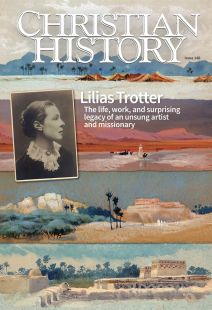

[Lilias Trotter, 10 Year old Portrait—Used by permission of Lilias Trotter Legacy and Arab World Ministries of Pioneers]

Famous English writer, artist, and critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), in his 1883 Oxford lecture “The Art of England,” tells of meeting a young woman who challenged his prejudice about female artists. “I used to say,” Ruskin wrote, “in all my elementary books, that except in a graceful and minor way, women could not draw or paint. I’m beginning to bow myself to the much more delightful conviction that no one else can.” Exhibiting a half-dozen framed pages from Lilias Trotter’s Norwegian sketchbook for his students to copy, Ruskin advised, “You will in examining them, beyond all telling, feel that they are exactly what we should like to be able to do, and in the plainest and frankest manner sh[o]w us how to do it—more modestly speaking, how, if heaven help us, it can be done.”

Unrealized potential

Eight decades later, Sir Kenneth Clark, in Ruskin Today (1964), mentioned Ruskin’s “ecstasy” over the drawings of Trotter; but he noted that she was no longer remembered in Clark’s own day. Today the exhibition paintings that Ruskin raved over, along with 34 other leaves from Trotter’s sketchbook, are buried in the Print Room of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England, in the Ruskin Art Collection—a hidden testament to potential recognized, promise unrealized.

Born Isabella Lilias Trotter on July 14, 1853, into the large and wealthy family of Alexander and Isabella Trotter, Lilias grew up in London’s West End during the golden age of Victoria, in all the privilege such surroundings afforded her. She experienced the private tutelage of governesses and the stimulation of Continental travel by horse-drawn carriage.

Clear to family and friends from an early age, Trotter’s spiritual receptivity increased as she matured. It quickened in her early twenties during attendance at a set of conferences for those seeking a deeper spiritual life (see pp. 18–20). There Trotter found her understanding of Christian faith and practice clarified and solidified.

Her freshly kindled faith soon found a conduit in volunteer mission work with the then-fledgling YWCA at Welbeck Street Institute, a hostel for London’s working girls. She helped open London’s first affordable public restaurant for women who otherwise had to eat bag lunches on city sidewalks. Her heart also reached out to prostitutes at Victoria Station. Her part-time work there eventually evolved into the full-time role of “honorable secretary.”

Parallel to this zeal for service was a passion for art born of innate sensitivity to beauty, matched by an exceptional artistic talent. Trotter’s mother initiated the fortuitous meeting of Ruskin and Trotter during a time when mother and daughter were staying at the Grand Hotel in Venice. Upon learning that the great master was residing at the same hotel, Mrs. Trotter sent Ruskin a note asking for his assessment of her daughter’s work.

Ruskin’s response is immortalized in “The Art of England”: “On my somewhat sulky permission a few were sent, in which I saw there was extremely right minded and careful work.” Thus began the unique friendship between the 57-year-old Ruskin—artist, critic, social philosopher—and 23-year-old Trotter. Ruskin, author of The Stones of Venice (1851), the definitive history of the city’s art and architecture, took her under his wing, bringing her on sketching expeditions and inviting her to study with him upon her return to England. He recognized a rare artistic talent, which, if cultivated, he said, would make her one of England’s “greatest living artists.”

Deep heartsight

It is impossible to overestimate the effect this distinguished mentor and friend had on Trotter. She viewed the world as Ruskin did, with “heartsight as deep as eyesight,” to borrow a phrase he used to describe his hero, painter J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851). Ruskin believed that without a knowledge of drawing, one could not fully appreciate nature. Techniques, he believed, must be acquired hand-in-hand with the skill of “learning to look.”

If Ruskin was the consummate teacher, Trotter was the ideal student. Ruskin said in his lecture, “She seemed to learn everything the instant she was shown it, and ever so much more than she was taught.” To Trotter he wrote, “I pause to think how—anyhow—I can convince you of the marvelous gift that is in you.” Just as Ruskin had championed John Millais (1829–1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), he was prepared to advance Trotter’s career.

As Trotter’s immersion in painting deepened, however, so did her commitment to her spiritual calling. Ruskin complained of the toll her ministry was taking on their friendship and expressed concern that her work in London was affecting the character of her art. He invited her to Brantwood, his Lake District home, in May 1879 to put before her the brilliant future he maintained would be hers if she would give herself fully to the development of her art. Dazzled, Trotter wrote to a friend that Ruskin believed “she would be the greatest living painter and do things that would be Immortal.” As a talented teacher and powerful cultural leader, Ruskin could launch her career single-handedly. But the offer came with a caveat. She would have to “give herself up to art.”

This challenge shook Trotter to the core. After days of agonizing prayer and deliberation, she knew she had to make a choice. She wrote, “I see clear as daylight now, I cannot give myself to painting in the way he means and continue to ‘seek first the Kingdom of God and His Righteousness.’” Her decision disappointed many friends and family members. Indeed, anyone venturing into the Ashmolean Museum will find it heart-wrenching. There in frame after frame, are works by Ruskin’s disciples—Millais, Rossetti, Holman Hunt (1827–1910), Ford Maddox Brown (1821–1893)—whereas Trotter’s works, clearly their equal in artistry if not complexity, are filed away, viewable only by request.

Trotter returned to London and threw her energies into her city work—a vocation of caring. She continued her friendship with Ruskin as well as her painting, but now with “a grand independence of soul” that she would later describe as “the liberty of those who have nothing to lose because they have nothing to keep. We can do without anything while we have God.”

Almost 10 years later, May 1887, at a foreign missions challenge, Trotter felt the call of God to bring the gospel to the people of Algeria. She quickly applied to the North African Mission and was turned down for health reasons. With her own resources, she made plans to go to Algeria to work alongside, but not officially connected with, the same mission. In March 1888, at age 35, she set off with Blanche Haworth (1854–1918) and Lucy Lewis (Lewis left after a year) to Algiers, where she knew no one and not a word of Arabic.

A people "bright and living"

Trotter’s early Algerian journals and letters (1888–1898), followed by 30 compact leather-bound page-a-day diaries (1899–1928) and travel journals, detail her daily activities and the inner spiritual life that sustained this unthinkably difficult ministry. From these records, illuminated by exquisite watercolors and strong sketches, a museum in miniature emerges of a country intimate and varied and a people “bright and living.” In retrospect one can see how Trotter’s first 35 years had prepared her for a vocation—a passion—that would ignite and hold her heart in Algiers for her remaining 40 years of life.

The team’s first objective was to master Arabic, an imposing task. Next was to gain access to local Arab homes. From their rented flat in the French quarter, the women ventured into the Casbah (old city), gaining entrance to the homes through the children and going into the cafés with Scripture cards written laboriously, one new word at a time. With their limited vocabulary, they asked the men to read the cards aloud for their understanding!

Trotter’s dream to live among the Arabs in the Casbah came to fruition in 1893 with the purchase of an old, fortress-like house, the base of their ministry for years to come. Their early efforts were varied and flexible; Sunday classes for water carriers were their first venture. Yet all the while they were developing incarnational relationships with the local people. As numbers gradually increased, horizons widened: the villages on the mountains and the great southern lands beyond. They mapped winter journeys outward in these unreached regions, taking their first major itineration in 1893 and establishing a “station” the following year.

Yet for every early advance, setbacks followed. They encountered substantial resistance to Christianity and increasing political tensions. The 1896 French Entente against Britain blocked freedom of travel in the country and restricted them to the most limited program in Algiers as the nationals backed away from them out of fear of association.

They also found an inner spiritual battle as intense as the outward challenges; Trotter wrote of the “testings on the battle-field where the inner life failed, the nerve strain of the climate, the pressure on our spirits of the Satanic forces with which all teems out here, the lessons which we thought we knew” and had “to be learnt afresh.”

Even during the hardest of years, Trotter maximized every opportunity. She employed young French colporteur evangelists; her team developed hand-printed Scripture and supplementary texts for limited distribution, and they translated portions of the Bible into colloquial Arabic. The clouds lifted a bit in 1903 following a positive visit to Algeria from Britain’s King Edward.

This formed a turning point for the struggling band of workers. With the 1906 purchase of a rambling old native house in a nearby suburb, Dar Naama—“House of Grace”—became their official headquarters. Now they could provide summer respite for workers and launch unforeseen ministries. Soon it became the site of conferences, rallies, youth camps, Scripture translation revision meetings, the home base for village work along the plateau, temporary housing for Arab families, and more. In 1907 the work was organized under the name Algiers Mission Band (AMB).

Faith tested and applied

The following years, though not without struggle, were marked by an increase in workers, base stations and substations, ministries, and strategies for more effective communication with the AMB’s growing Arab “family.” Trotter seasonally alternated the winter work in the Southlands with springtime and autumn mountain and village visitation.

She connected stations through an in-house magazine, El Couffa, and built bridges between these ministries and prayer supporters in Europe through intimate round-robin journals illustrated with tiny drawings and photographs. Later she printed illustrated reports supplemented by urgent updates—all designed to make the land and the people “vital and living” to those who would never have personal contact with the work.

Trotter’s devotional leaflets and books (see pp. 11, 21) were born out of the practical realities of her own tested faith. She also wrote in Arabic and English The Sevenfold Secret (1926), based on the seven “I AM’s” of Christ from the Gospel of John (see pp. 30–34), for the Sufi mystics in the Southlands.

While Trotter did not crave a leadership role—maintaining that one of the great joys of heaven for her would be relief from the burden of leading—she didn’t shirk it. She developed and maintained work over a vast and varied country, recruited and trained workers, developed ministries to Arab families (including becoming a matchmaker for Christian marriages!), and trained converts toward self-sufficiency through industrial farming and native crafts. All the while she kept before the team the original, albeit sometimes tested, objective: to evangelize the outlying and unreached interior as opposed to making stations an end in themselves.

Trotter spent the last three years of her life confined to her bed at Dar Naama—but continued to oversee virtually every aspect of the AMB. Her room was the control station of the mission, her agenda book the log, and she maintained a vast correspondence. She continued to be involved in policy and vision, plotting journeys on the map spread before her and following the daily operations of each station. On August 27, 1928, at age 75, she died, with members of her Arab and mission “family” gathered around her bed. She was buried in Algiers, the place she called home, among those she considered family.

How did Trotter manage to found and lead this mission work with both grave opposition and limited resources? And how did she resolve the extraordinary tension between the two almost paradoxical aspects of her nature: the visionary, strategist, and pioneer with the artist, mystic, and contemplative?

Something afresh

In her diaries and journals, a vision of the invisible emerges. Francis Bacon wrote that God has two textbooks—Scripture and Creation—and that we would do well to listen to both. Trotter did. In the early mornings, she studied Scripture and texts from her daily devotional volume, Daily Light. One of her earliest letters states:

I have found a corner in the Fortification Woods, only five minutes from the house, where one is quite out of sight, and I go there every morning with my Bible from 7:15 till 8:30—it is so delicious on these hot spring mornings, and God rests one through it for the whole day, and speaks so through all living things. Day after day something comes afresh.

Throughout her life she sought out quiet—a rooftop refuge, a desert palm garden, a Swiss forest of firwood, an Arab prayer room, the confines of her bed—to listen to God’s voice through Scripture and prayer. And she read God’s “work,” seeing lessons in nature’s design and processes, lessons that revealed to her the Creator. Her diaries are filled with paintings of the natural world, and her language is laced with natural expressions: “The daisies have been talking again”; “The word of the Lord came in a dandelion”; “A bee comforted me this morning”; “The martins have been reading me a faith lesson”; “The milky looking glacier torrent spoke with God’s voice”; “The snow is speaking.”

We cannot document her influence in statistics or in visible institutions. However, when she died, the Algiers Mission Band was on solid footing: 30 members strong in 15 stations and outposts, united in her vision to bring “the light of the knowledge of God, in the face of Christ” to the people of that land, from the cloistered world of Arab womanhood to the male Sufi mystics in the desert.

During her 40 years in North Africa, she pioneered means, methods, and materials, some considered to have been a hundred years ahead of her time. Her dream for a church visible was never realized in her lifetime, but her diaries record scores, possibly hundreds, of national believers, and today Christians still worship in Algeria.

On the final image of Parables of the Cross—a sprig of new life growing from seemingly dead twigs of wood-sorrel—she penned the words from Revelation “Their works do follow them.” In writing of this truth, she prophetically supplied perspective on her own legacy and the legacy of all who invest in the kingdom of God: “. . . as these twigs and leaves of bygone years, whose individuality is forgotten, pass on vitality still to the new-born wood-sorrel. God only knows the endless possibilities that lie folded in each one of us!” CH

By Miriam Huffman Rockness

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #148 in 2023]

Miriam Huffman Rockness is author of A Passion for the Impossible and Images of Faith, editor of several editions of Trotter’s writings, and chair of the Lilias Trotter Legacy Board. This article is adapted from A Blossom in the Desert and “About Lilias: Missions” at liliastrotter.com.Next articles

Learning to see

John Ruskin loomed large over an art world and a culture wrestling with both truth and beauty

Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson & Jennifer TraftonMinds occupied with heaven

Organizing laypeople for piety and service in the Nineteenth Century

Kevin Belmonte