Alternative economies

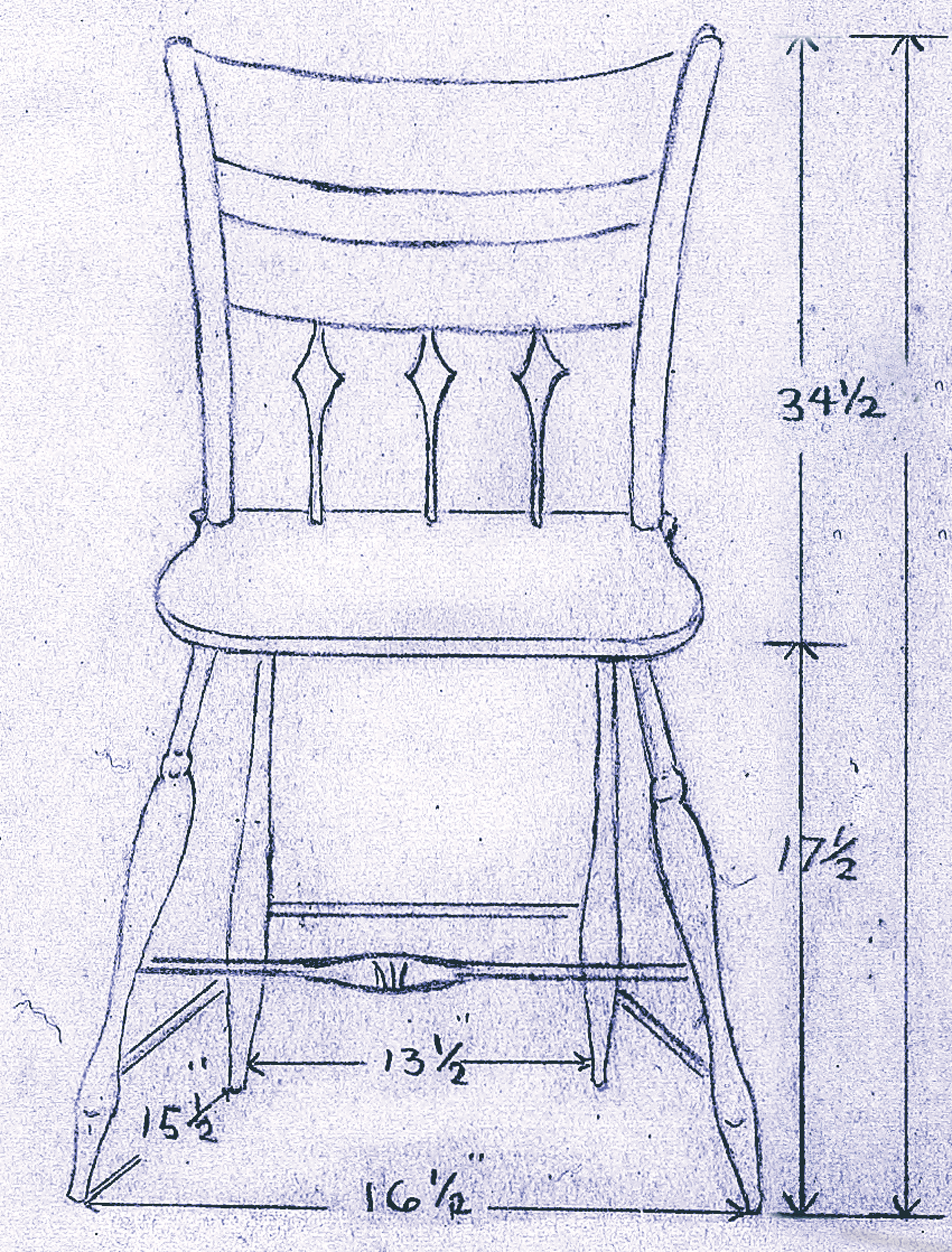

[Lon Cronk, Shaker Dining Table and Chairs, c. 1937—National Gallery of Art / [CC0] Wikimedia]

Your hands to work and your hearts to God and a blessing will attend you” was the Shaker movement’s most famous slogan; even inspiring the famous Ken Burns documentary about them. At the movement’s peak in the nineteenth century, more than 5,000 members lived in over 20 settlements. Now sites where they once lived and worked are long-closed or open as museums—except for the Sabbathday Lake Village in New Gloucester, Maine, where a few living Shakers maintain their old ways.

Today their legacy lives on in music (most famously the song “Simple Gifts”) and a tradition of architecture, farming, and furniture-making. Shakers were known even in their own day for shrewd and honest business dealings and imaginative craftsmanship. They are responsible for inventing many things we use frequently: condensed milk, circular saws, metal pens, paper seed packets, apple parers and corers, flat-bottomed brooms, clothespins, fertilizer spreaders, and a version of the automatic washing machine.

Plain and sturdy

Founded in England in the 1740s, the group—known formally as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing—combined unorthodox theology with communal celibate living and a complete willingness to engage in the market, but on their own terms. They taught that followers of Christ should refrain from all sexual relations, confess their sins to each other, and worship through a form of ecstatic shaking that gave them their common name. Their most famous leader in the United States was Mother Ann Lee (1736–1784), who joined the movement in England in the 1770s and brought it to America in 1774. Many Shakers considered her to be a second appearance of Christ.

Shakers in the United States founded communities throughout New England and eventually the Midwest. They built plain but sturdy and attractive buildings in which they housed men and women in separate wings and supported themselves through farming and the making of furniture. (As a celibate order, they gained new members either through conversion or by raising young orphans who occasionally decided to stay with the community.)

Though they first sought to feed, clothe, and house their own, they readily sold their products to others as well. They even developed an early version of assembly-line furniture production. From the 1820s on, the central Shaker settlement in New Lebanon, New York, designed furniture for all the communities and then shipped kits to other settlements for assembly.

Work was a religious commitment for the Shakers. Mother Ann, author of the “hands to work and hearts to God” dictum, also told her followers, “Do your work as though you had a thousand years to live and as if you were to die tomorrow.” Father Joseph Meacham, an early successor of Mother Ann’s, commented that “All work done, or things made in the Church for their own use ought to be faithfully and well done, but plain and without superfluity. All things ought to be made according to their order and use.”

The Millennial Laws that governed the community forbade excessive adornment, and, despite their ingenuity, Shakers encouraged their craftsmen and women not to claim their work for fear this could lead to pride; they rarely applied for patents.

“To the Shaker, everything is a gift from God,” Brother Arnold Hadd, one of the last living Shakers, said in a 2015 interview. “Everything. Whatever we’re doing, that’s a gift. And we try to labor on that gift to bring it forth into a perfection.”

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #137 in 2020]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is managing editor, Christian HistoryNext articles

Self-serving vice or society-building virtue?

The long-standing influence of Max Weber’s linking of Protestantism and capitalism

Kenneth J. BarnesChristian History timeline: Market matters

Some ways Christians have preached, thought about, shaped, critiqued, and participated in economic life throughout church history

The editorsBringing profit to neighbors

The church and economic theories from zero-sum to mutual benefit

Jordan J. Ballor