“Sing and make melody in your heart”

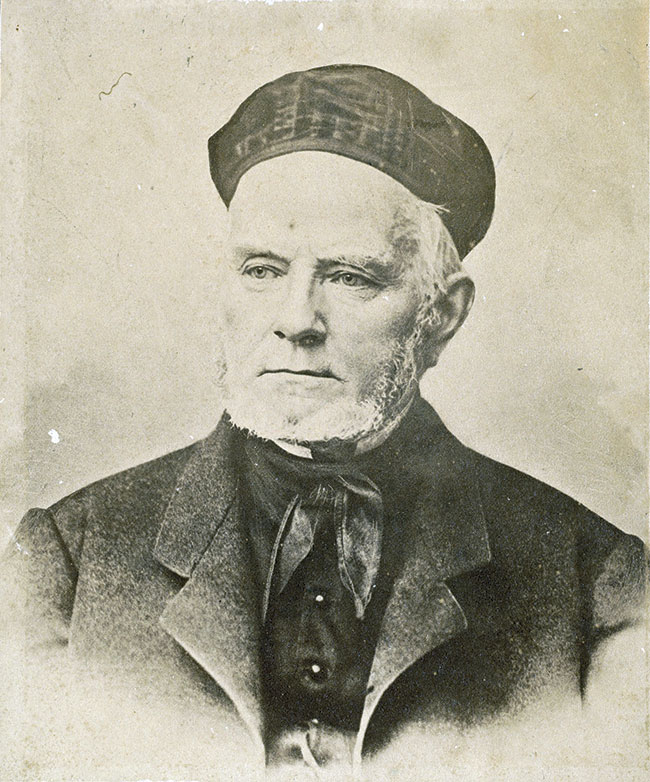

[Oliver Ditson's Lowell Mason (1792–1872). Printed portrait on cardboard (1857 to 1900)—Oliver Ditson & Co., Boston / [Public domain] Wikimedia]

Wherever the Christian faith has taken root, the history of the Bible and the history of hymnody have grown up together. This synergy existed from the beginning in America. A printing press in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the North American colonies’ first such enterprise, published the Bay Psalm Book as its very first work. This metrical paraphrase of the Psalms appeared in 1640 and was then reprinted over 30 times during the next century and a half.

The Bay Psalm Book’s popularity meant that when New England Puritans ventured beyond their primary focus on the Bible itself, their public singing—and often personal reading—was still Scripture in another form. The Bay Psalm Book’s paraphrased translation, made directly from the Hebrew, was the work of three university-educated ministers, including John Eliot, who would later labor to translate the Bible into Algonquian (see pp. 32, 36).

The Bay Psalm Book has often been criticized for its clunky style, as in its rendering of Psalm 23:

The Lord to mee a shepheard is,

want therefore shall not I.

Hee in the folds of tender-grasse,

doth cause mee downe to lie.

But no one should doubt how much it kept Scripture central as Puritans sang in church or used the book for family worship and private reading.

This clunky hymn book would soon have competition. American hymnody evolved significantly in the eighteenth century primarily because of the popularity of English hymn writer Isaac Watts (1674–1748). Before Watts, English, Scottish, and colonial Protestants restricted their singing to biblical paraphrases, such as the Bay Psalm Book, for fear that substituting unreliable human invention for the pure Word of God would contaminate their public worship.

Watts, an English Congregationalist, dared to loosen up. The title of his most widely reprinted collection explained what he hoped to accomplish: the Psalms of David, Imitated in the Language of the New Testament, and apply’d to the Christian State and Worship. Early American editions of Watts’s Psalms of David included a text from Luke 24:44 to justify a kind of paraphrasing combined with original writing that many at the time regarded as dangerously radical: “All things must be fulfilled which were written in . . . the Psalms concerning me.”

Our eternal home

Watts deferred to tradition in the first paraphrase he prepared for Psalm 90. Its rendering was freer than what the Bay Psalm Book authors attempted, but not by much:

Through every Age, Eternal God,

Thou art our Rest, our safe Abode;

High was thy Throne e’er Heaven was made,

Or Earth thy humble Foot-stool laid.

Yet when his second treatment of the same psalm moved further from the literal, he gave English speakers a hymn that remains iconic to this day:

Our God, our Help in Ages past,

Our Hope for Years to come,

Our Shelter from the stormy Blast,

And our eternal Home.

Other hymns in the same collection drew out Christian meanings from psalms even more explicitly. Psalm 96 as rendered by the KJV begins, “O sing unto the Lord a new song: sing unto the Lord, all the earth. Sing unto the Lord, bless his name; shew forth his salvation from day to day.” For Watts it became:

Joy to the world, the Lord is come,

Let earth receive her king:

Let every heart prepare him room,

And heav’n and nature sing.

Many of Watts’s American contemporaries agreed that this move beyond strict biblical paraphrase actually made hymns more effective for driving home the central message of the Bible. As a pastor in Northampton, Massachusetts, Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) spoke for those in agreement.

Edwards (see pp. 11–13) was an early supporter of reforms transforming the soundscape of New England churches from the 1720s on—moving from “usual” singing (psalms lined out and sung haphazardly) to “regular” singing (psalms sung in harmony, sometimes with instrumental accompaniment). In just a few more years, Edwards’s congregation not only embraced the newer way of singing psalms, they included the newer hymns as well. In 1742 he authorized replacing one of the three psalms normally sung in the Sunday service with a hymn by Watts because he “saw in the people a very general inclination to it”—in fact, so much of an inclination that his congregation would have been willing to shift over entirely to the new hymns. Edwards’s response was to mix the new with the old, which produced a blended worship that, as he saw it, gave “universal satisfaction.”

Two years later Edwards published a defense of the new hymns—specifically how their use could vivify the Bible’s most important message. Edwards argued that Scripture nowhere prohibits hymns of ordinary human creation any more than it prohibits prayers of ordinary human creation. Positively considered, Edwards said that it was “really needful that we should have some other songs besides the Psalms of David,” especially to express “the greatest and most glorious things of the Gospel, that are infinitely the great subjects of [the church’s] praise.”

Rather than singing always “under a veil” where “the name of our glorious Redeemer” was never mentioned directly (i.e., the Psalms), Edwards understood the hymns of Watts as strengthening core biblical teaching about salvation in Christ.

Liberated hymnody

Throughout the rest of the British Empire, others were moving farther and faster in following the same logic. It was the era when Philip Doddridge (1702–1751), John Cennick (1718–1755), Anne Steele (1717–1778), John Newton (1725–1807), William Cowper (1731–1800), Augustus Toplady (1740–1778), and especially Charles Wesley (1707–1788) made the expansion of popular hymnody coterminous with the spread of evangelical religion. A hymnody liberated from strict biblical paraphrase, but still fully dependent on the Scriptures, resulted.

To be sure this liberation led to some hymns from which biblical content faded almost entirely away. But three landmark American collections show how hymnody that depends on Scripture but is liberated from strict paraphrase made biblical truth come alive for congregations as they sang and for individuals reading or recalling music with lyrics sealed in their hearts.

Companion for the pious

The first of these collections is the Pocket Hymn-Book: Designed as a Constant Companion for the Pious Collected from Various Authors. The United States’ early history witnessed one of the most dramatic expansions of Christian churches in the modern era, an expansion driven especially by Methodists. Historian David Hempton observed that “the most distinctive, characteristic, and ubiquitous feature of the Methodist message, indeed of the entire Methodist revival, was its transmission by means of hymns and hymn singing.”

These Methodist hymns feature the Bible from first to last. Methodists published a plethora of worship aids, but none as widely used as the Pocket Hymn-Book. Expanding slightly from year to year (285 hymns in 1790, 320 in 1817), it was priced to sell (50 cents in 1800, around $11 today) and may have touched more American homes in that era than any book except the Bible itself.

The collection opens with a selection by Charles Wesley, whom historian Frank Baker once described as a kind of walking concordance: “His verse is an enormous sponge filled to saturation with Bible words, Bible similes, Bible metaphors, Bible stories, Bible ideas.” This opening hymn, originally 18 stanzas, appears as an abridgement that many others would also reprint and begins memorably:

O for a thousand tongues to sing [Ps. 119:172],

My dear Redeemer’s praise!

The glories of my God and King [Ps. 145:1],

The triumphs of his grace!

Each of the later verses carries on with more Scripture in song:

He breaks the power of cancell’d sin,

He sets the pris’ner free [Is. 61:1];

His blood can make the foulest clean [Is. 1:18],

His blood avail’d for me [Gal. 2:20, loosely].

As Methodists sang these hymns, soon followed by Protestants of all sorts (and from the mid-twentieth century by Catholics as well), scriptural phrases, scriptural allusions, and (most important) scriptural teaching filled the consciousness of those who sang.

More spiritual songs

Two other nineteenth-century hymnbooks, which differ in almost every other way, illustrate the same biblical grounding and a similar capacity to inculcate biblical teaching. Richard Allen (1760–1831), founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, published two editions of A Collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs (1801). Its 64 hymns appear without introduction, indexes, or users’ helps of any kind.

Just as different is the Sabbath Hymnbook of 1858, edited by the nation’s premier composer of church music, Lowell Mason (1792–1872); with the president and leading professor of Andover Seminary, Austin Phelps (1820–1890); and Edwards Amasa Park (1808–1900).

This large and sophisticated book contains 1,290 hymns plus another 24 doxologies along with chants for 57 psalms, as well as an extensive introduction and seven indexes spread over 131 tightly printed pages. It came to the public by seven different publishers from five cities and was accompanied by a tune book and a hymnal with text and tunes.

One of the book’s indexes, however, reveals the Sabbath Hymnbook’s close kinship with Richard Allen’s humble effort—a 17-page “Index of Passages of the Scriptures,” with thousands of references specifying direct biblical sources for the hymns. The editors wrote self-consciously about their dependence on Scripture, so much so, they said, that “at one time, [they were] somewhat inclined to arrange the hymns of this volume according to the Biblical sources whence they were derived.”

Richard Allen offered no explanation for his selection of hymns, but his reliance on the Bible was every bit as thorough as the Sabbath Hymnbook. One hymn, written by an enslaved author, directly addresses an individual who sings,

O that I had a bosom friend

To tell my secrets to. . . .

How do I wander up and down,

And no one pities me.

In answer the hymn offers an extended versification of John 15:13–14—“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends. Ye are my friends, if ye do whatsoever I command you.” To the friendless soul, the hymn addresses these words:

Did Christ expire upon the cross

And is he not thy friend? . . .

The Saviour is thy real friend,

Constant and true and good.

Allen wrote a decidedly Methodist book, but with several features explicitly directing it for the sons and daughters of Africa. With an eye to this main audience, hymns include references to the Exodus that freed Israel from enslavement in Egypt. Two elaborate on Jesus’s story of the rich man who scorns Lazarus, the beggar at his gate.

Most revealing is a hymn that Allen probably wrote himself. This 14-stanza composition begins with scriptural phrases making a standard Methodist appeal:

See! how the nations rage together!

Seeking of each others blood;

See how the Scriptures are fulfilling!

Sinners awake and turn to God.

Then Allen riffed on a profusion of biblical material: “the fig-tree budding” (Matt. 24:32–35), “wars . . . to come before that dreadful day” (Matt. 24:6); the harvest “in danger of wasting away” (Luke 10:2); “the Lord in clouds descending” (Rev. 1:7). In a fashion foreign to the strict apoliticism of White Methodists of the era, this hymn also contains social references calling “the land” and “the nation” to:

Turn and find salvation

While now he offers you free grace.

Aiding in the closet

For its part the Sabbath Hymnbook—from its opening three hymns, which paraphrase the Lord’s Prayer, to the final section of psalms marked for chanting—offered extended meditations on the biblical themes prominent in British evangelicalism and most American denominations.

Whether canonical authors of eighteenth-century English evangelicalism or contemporary voices from Scotland and the United States, the book’s authors were unified in constant, creative, and meditative engagement with Scripture.

The editors hoped their collection would be used first for Sunday worship, but also, in keeping with how such books had long functioned, “to aid in the more private social devotions, in the conference room, the family, and the closet.” In their hymns, like those of Richard Allen, they wrote that “we have aimed to furnish a book of real life.”

And so it has continued. Anchorage in Scripture is not always as obvious in hymn lyrics from the last century and a half, though the recent boom in worship songs includes many examples that bring congregational singing back at least partially to the paraphrases of the

Bay Psalm Book.

As believers sing from Lamentations 3:22 (“Great is thy faithfulness”) to hearten souls under pressure, from Luke 23:42 (“Jesus, remember me”) to seek God’s mercy, or from Isaiah 55:12 (“The trees of the field will clap their hands”) to express their joy in the Lord, the written Word of God comes freshly alive. Hymn writers harvest the Scriptures for spiritual encouragement, and, as believers are nourished by the hymns, they are sent back to the Bible.

CH

By Mark A. Noll

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #143 in 2022]

Mark A. Noll is research professor of history at Regent College, professor emeritus of history at the University of Notre Dame, and author of In the Beginning Was the Word, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln and America’s Book: The Rise and Decline of a Bible Civilization.Next articles

Old book in a new world

The story of Bible translations in America centers around the KJV

Chris R. ArmstrongAttackers and defenders

How “higher criticism” developed, came to America, and provoked a response

James C. Ungureanu