Aftershocks

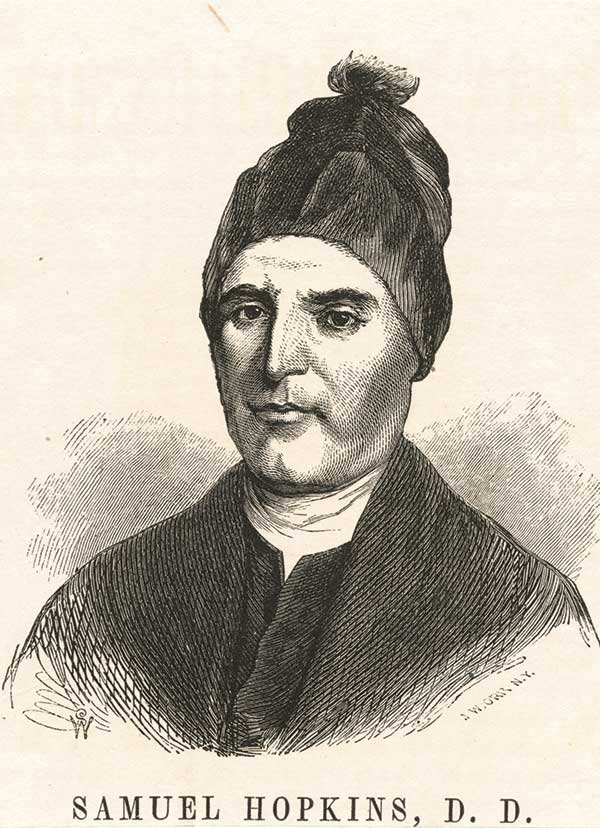

[Above: John William Orr, Samuel Hopkins, c.1870, wood engraving—NYPL / Public domain, Wikimedia]

In the decades following the First Great Awakening, the church continued to see exponential growth on both sides of the Atlantic. Membership rolls exploded with new converts who experienced the “new birth.” Subsequently the Great Awakening’s rippling effects would spread over North America, both to the colonists and to the Native American tribes; over Europe; and eventually over Asia. Ultimately the collective beliefs and convictions that sprang from the First Great Awakening became a powerful global movement.

An uncontained movement

Unlike some religious movements before it, the First Great Awakening’s influence was not restricted to a single Christian tradition, class, social stratum, or geographic location. Instead it began and continued as a movement both transatlantic in scope and transdenominational in order. After the events of the Great Awakening had concluded, the mark of its piety remained on most of the Western world. George Whitefield had ministered to nearly every British American colony, traveling from Georgia to New England and places in between. On the other side of the Atlantic, his friend, John Wesley, traveled over 250,000 miles on horseback and preached about 40,000 sermons in Great Britain. Both men’s expansive reach and unconventional “out of doors” itinerant preaching led to unprecedented growth among people of all backgrounds.

This growth and reach included all of North America. Indigenous Americans and people of African descent also experienced personal conversion and change in the years that followed. For example, Methodist churches in Pennsylvania saw as many as 380 African and Native American members actively engage in church functions in the late eighteenth century. What’s more, these minorities worshiped alongside their White counterparts in the same buildings. The gospel message preached in the Great Awakening called all people to repentance. To that end Whites, Blacks, and Native Americans found commonality in their religious experience.

Worldwide awakening

The evangelical movement that began during the Great Awakening eventually gave rise to modern, global, Protestant missions. Revivalists of the Great Awakening also produced many notable works that were widely read in Europe. Several of Jonathan Edwards’s books were distributed to pastors, influencing their theology and evangelism. One British pastor who felt that influence was Andrew Fuller (1754–1815). Fuller immersed himself in Edwards’s writings, specifically Treatise on the Religious Affections (1746). He recorded,

I think I have never yet entered into the true idea of the work of the ministry. . . . I think I am [lacking in] the ministry, as I was [lacking in] my life as a Christian before I read Edwards on the Affections. I had never entered into the spirit of a great many important things. Oh for some such penetrating, edifying writer on this subject!

Several other ministers of the Reformed pedigree would apply Edwards’s theology in their defense against various heresies in the eighteenth century.

Taking on Edwards’s strong evangelical notions of calling sinners to repentance, Fuller and other Baptists formed the Baptist Missionary Society in 1792. Their passion to “propagate the gospel” among unreached peoples became a hallmark of eighteenth-century Calvinistic Baptists, a nod to the Great Awakening’s firebrand activism that began these missionary efforts. Fuller’s close friend, William Carey (1761–1834), also read Edwards’s writings. Carey was enthralled by his missionary account of The Life of David Brainerd (1749); so much so that he would go to the unreached people in Calcutta, India. There Carey spent over 40 years tirelessly working on Bible translations and educational reforms. Under his ministry hundreds were converted. In a missionary sermon, Carey called his listeners to “expect great things from God; attempt great things for God.”

From revival to revolution

The Great Awakening’s impact would be felt in every facet of life, including in the social and political realms of the United States. How to ascertain “true religion,” or authentic Christianity, was on the minds of the awakened. One way to live out a truly Christian “disinterested benevolence” (the practice of seeking the interests or welfare of others as opposed to self-interest) was to “love your neighbor.” But who is your neighbor? For many Christians during the late eighteenth century, loving one’s neighbor meant ending all forms of oppression, especially for those who were the most oppressed, namely, enslaved Africans. Close friend and student of Jonathan Edwards, Samuel Hopkins, became a patriot and abolitionist during the late eighteenth century. Hopkins fused Edwards’s moral ethics and theology of love into a socioreligious ethic to call for an immediate nationwide emancipation. He argued that

Love to our neighbor, which God’s law requires, is certainly universal, disinterested good will, since it is a love which will dispose us to do good unto all. . . . “All things whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so to them,” which is included in loving our neighbor as ourselves, will set at liberty every slave.

Hopkins longed to see a global revival. However, the inhumane treatment of enslaved Africans, and the institution of slavery in general, prevented any type of work of God. Therefore Hopkins and many others among the awakened strongly advocated for ending the evil enterprise.

With the questioning of slavery also came the upending of the standing church order. People questioned both church and government and emphasized personal conviction. This would eventually lead to the American Revolution. Recounting the events, President John Adams observed that “The Revolution was effected before the war commenced.” Indeed the revolution itself began “in the minds and hearts of the people, a change in their religious sentiments of their duties and obligations.” While the Great Awakening was not part of the American Revolution, it was a spiritual revolution and served as a progenitor for American independence. While scholars debate how the First Great Awakening influenced social and political thought, it is undeniable that the Great Awakening laid a theological and intellectual groundwork for what came next. CH

By John T. Lowe

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #151 in 2024]

John T. Lowe is a professor of history at the University of Louisville.Next articles

Words that bring the dead to life

Issue advisor Michael McClymond walks CH through revival preaching

Michael McClymond“The flame spread more and more”

A firsthand account of the revival at Cane Ridge

Colonel Robert Patterson