“Your clan is Salvation”

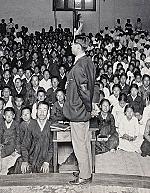

[Above: Outdoor Revival Gathering, mid-20th Century. Eastern Africa—Public domain, Beautiful Feet]

Dora Sabiti returned home from school in western Uganda rather puzzled. Her teacher had asked the class to name their tribe, clan, and clan taboo. She had no idea what this meant. Her parents told her, “Your tribe is Born Again (Oweishemwe), your clan is Salvation (Okujunwa), your clan taboo is Sin (Ekibi).”

Dora’s parents were East African revivalists, and her father, Erica Sabiti (c. 1903–1988), would become the Anglican archbishop of Uganda in 1966. For them a focus on ethnic or racial identity was antithetical to the gospel. The Sabitis wanted their children to accept a new identity in Christ crucified, connecting them with saved people around the world.

The East African Revival is best understood within a history of African renewal movements and global evangelicalism. Revivalists focused on rigorous examination of self and had a strong sense of affiliation with the worldwide church. They also responded to regional challenges, such as displays of racial superiority by White missionaries and colonialists. These, the revivalists said, were sins that distracted from preaching the gospel. Similar challenges were being faced elsewhere in Africa by prophet movements, like those led by William Wade Harris (1860–1929) in West Africa and Simon Kimbangu (1887–1951) in Congo.

The Rise of the Saved People

Early signs of renewal appeared in the Anglican Church of Uganda in the 1920s. Revival exploded in Rwanda in 1933 and moved into Kenya in 1937, Tanzania in 1939, and then to South Sudan, Burundi, and Congo, energizing a number of Protestant denominations. Leaders adapted tools of international evangelicalism, such as itinerant preaching and Christian conventions. In 1947 preachers William Nagenda (1912–1973) and Yosiya Kinuka (1905–1981) visited Switzerland and Britain, the first of many international evangelistic tours taken by revivalists. Some Western missionaries working in East Africa joined the revival movement and took its teaching back to the United States, Australia, and Europe.

Revivalists became known as the Balokole or Wokovu, Luganda and Swahili words respectively, meaning “Saved People.” Unlike the movements started by Harris and Kimbangu, the Balokole largely remained within mission churches. Laypeople led the movement, but by the 1960s, a number of revivalists had become senior church leaders. They influenced the adoption of revival values into the church and wider society.

These leaders, some praised in Western evangelical circles, were committed to global ecumenical discussions at a time when Western evangelicals and ecumenical Protestants often viewed each other with suspicion. In 1971 Bishop Festo Kivengere (1919–1988), who shared platforms with Billy Graham, established African Evangelistic Enterprise to spread revival across the continent. In 1974 church leader John Gatu (1925–2017) called for a moratorium on Western missions so African churches could become independent vehicles for evangelism.

Zukula! Awake!

Many would trace the beginnings of the East African Revival to Simeoni Nsibambi (1897–1978), a prominent layman in the 1920s who organized groups to preach across Uganda, criticizing the complacency and “nominalism” of second- and third-generation Christians. Nsibambi was inspired by an earlier revival in 1893 led by George Pilkington (1865–1897) of the Church Missionary Society (CMS). Influenced by the Keswick Holiness movement (see CH #148 and #151) and the writings of the Indian evangelist Tamil David (1853–1923), Pilkington’s preaching on the inner self and the sanctifying power of the Holy Spirit had prompted a sudden rise in the number of evangelists preaching throughout East Africa.

In 1929 Nsibambi met John Edward “Joe” Church (1899–1989) of the Ruanda [sic] Mission. Making an instant connection, they prayed together for revival. Nsibambi encouraged recently trained evangelists and hospital orderlies to go to Rwanda as a mission field. Many went to Gahini, where Joe Church was stationed. At a Christmastime convention in 1933 came a sudden outpouring of confessions of wrongdoing and joyful expressions of forgiveness. Afterward the region saw a rise in church attendance, fellowship groups, and itinerant preaching. As in other revivals across the globe, these communal events created points of emotional intensity focused on the immediate need to accept Jesus Christ.

In 1936 Blasio Kigozi (1909–1936), a young Muganda deacon working in Gahini, returned to Kampala to deliver a message to the synod of the Anglican Church: Zukula! Awake! His sudden death before the start of the synod made his call for the reform of the church’s spiritual life more poignant, although plenty of clergy remained cautious about the revivalist approach. Bishop Simon Stuart (1892–1982) of the CMS had to walk a tightrope between different factions. Though appreciative of the evangelistic zeal of both revivalists and the Ruanda Mission, Stuart strove to remain faithful to Anglican tradition.

Action and reaction

Fellowship groups served as antidotes to the formality of the church. Meeting several times a week, the revivalists would pray together and organize evangelistic activity, then preach in public places.

Revivalists often challenged the priorities and traditions of their society. They sang,

You who trust the things of the world,

Why are you never satisfied with them?

For even your ancestors

Were not satisfied with them.

The revivalists were determined to reject the past. In doing so they rejected many cultural practices that other Africans wanted to maintain. Leaders of some ethnic groups accused revivalists of causing division among people by condemning drinking, polygamy, and the veneration of ancestors. They were scandalized by revivalists’ public and frank confessions of sexual sins. Colonial administrators were also worried about the tensions that could be stirred up by marketplace preachers accusing their neighbors of specific sinful behavior.

Revivalists also challenged class identities. For instance, two of the Balokole, Martha Yeremiah (dates unknown) and Josiah Kibira (1925–1988), shocked their community by getting married. Yeremiah was from a royal family and Kibira was a fisherman. As they saw it, their marriage witnessed to a new kind of clan formed through confession of sin and salvation. Later, as a bishop, Kibira would write about this clan in his book, Church, Clan and the World (1974).

Beyond that, the revival encouraged Christian women to be active at a time when mission churches did not ordain women. Women led fellowship meetings and preached alongside Christian husbands. When some women left polygamous marriages, fellowship groups supported them. In 1983 Kivengere ordained three women as priests, despite opposition within the Anglican Communion.

In addition revivalists demanded a recognition that Christian equality overcame racial difference. Colonialists and missionaries had created notions of race and ethnicity that bolstered their sense of European superiority and reduced the possibility of African autonomy. Revivalists, however, confronted White missionaries with the need to confess their superior attitude toward Black Africans, their “brothers and sisters in Christ.” This attitude, they said, put missionaries in conflict with their spiritual kin, with whom they would live eternally. Race, ethnicity, and gender were not to be understood as markers of difference, but as insignificant distinctions among family members. In response some White missionaries confessed and even called upon others to combat the “color bar.” Others considered the revivalists impudent or ungrateful for calling them to account.

Proper behavior?

In addition to race questions, some Western missionaries worried about revivalist behavior. Frank public confessions and vibrant forms of worship seemed closer to the practices of regional healing cults or prophet movements than to the more subdued or earnest piety with which missionaries were familiar. They wondered whether a true articulation of the gospel could come in such a loud, robust, and bodily form. The Balokole shared some of these concerns about what constitutes proper evangelical behavior and how behavior reflects proper belief.

Revivalists challenged one another. Sometimes they disagreed and divided. They competed in zeal and asceticism. Occasionally fellowships rejected those who deviated from revivalist beliefs or failed to practice rigorous self-discipline. When women’s ecstatic forms of worship seemed to exceed the control of church leaders, their self-expression was censured. It appeared that women only had an equal right to preach the gospel when they conformed to mainstream revivalist ways of doing so. And, although they preached and sang in local languages, many of the revivalists felt that cultural differences that appeared in forms of worship were erosions of evangelical orthodoxy.

The East African Revival is arguably the best-known revival movement in Africa because it most resembles the nineteenth-century revivals in Europe and America. It resonates with other renewalist movements in Africa in its focus on Jesus Christ, an expectation of changed patterns of life, and in its commitment to a worldwide Christian community as a response to immediate challenges in African society. Other renewal movements, like those of Harris and Kimbangu, left a legacy of new churches by blending African cultural practices into Christianity—such as using material objects in worship or by condoning polygamy. The Balokole shunned these approaches openly and adamantly. However, the Balokole and followers of Harris and Kimbangu applied biblical texts to their immediate contexts and considered missionaries lackluster in their commitment to biblical injunctions.

However, just like other revivalists around the world, African revivalists expected a rapid change of behavior among those who responded to their message, seeing themselves as part of the worldwide Christian church. Indeed for many foreign missionaries who witnessed this African transformation, it was clear that they all belonged to the tribe and clan of Christ. CH

By Emma Wild-Wood

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #153 in 2024]

Emma Wild-Wood is professor of African religions and world Christianity at the University of Edinburgh.Next articles

Century of the Holy Spirit

Pentecostal, Charismatic, and Third Wave Revivals of the Twentieth Century

Connie Dawson