A new model for missions

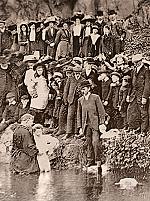

[Above: First U.S. Missionary Ordination, 1812—American Baptist Historical Society Archives, courtesy of Christopher Cook]

In the summer of 1806, five students met in a grove of trees at Williams College in Massachusetts to pray for divine guidance and to discuss their religious faith and calling. During an afternoon rainstorm, they sought refuge under a haystack. Undeterred, they continued their prayer meeting and consecrated their lives to overseas missions. This incident became a pivotal event in launching the foreign missionary movement of American Protestantism.

Several of those students at the Haystack Prayer Meeting carried their vision from Williams College to Andover Theological Seminary, where they created a more formal organization that eventually led to the establishment of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in 1810. Two years later five ABCFM missionaries—Adoniram Judson Jr. (1788–1850), Samuel Nott (1788–1869), Samuel Newell (1784–1821), Luther Rice (1783–1836), and Gordon Hall (1784–1826)—set sail for India, accompanied by three wives—Ann Hasseltine Judson (1789–1826), Rosanne Peck Hall, and Harriet Atwood Newell (1793–1812).

This was not an isolated event. Over the next two decades, American evangelicals founded and staffed dozens of voluntary societies to promote missions, moral reform, education, Bible reading, and prison reform. These included the American Education Society (1815), the American Bible Society (1816), the American Colonization Society (1816), the American Sunday School Union (1817), the American Tract Society (1825), the American Home Missionary Society (1826), and the American Society for the Promotion of Temperance (1826). This burst of Christian activism in the United States was a natural outgrowth of the Second Great Awakening, but it also sprang from other sources.

Churches cut loose

In the decades following the American Revolution, the United States experienced a profound shift in religious authority. State-sponsored religion slowly collapsed state by state under the weight of the First Amendment’s establishment and free exercise clauses, and religion had to find a new place in American society. This disruption created new space for populist churches, denominational institutions, and voluntary societies to flourish.

Lyman Beecher (1775–1863), one of the best-known pastors of the early 1800s, originally favored state-sponsored religion. When Connecticut officially disestablished the Congregational Church in 1818, Beecher said it was “as dark a day as ever I saw. The injury done to the cause of Christ, as we then supposed, was irreparable.” But he soon changed his mind, concluding that it was “the best thing that ever happened to the state of Connecticut. It cut the churches loose from dependence on state support. It threw them wholly on their own resources and on God.” He acknowledged the fears that “ministers have lost their influence,” but in fact, argued Beecher, “by voluntary efforts, societies, missions, and revivals, they exert a deeper influence than ever they could.” The American model of voluntarism ignited powerful religious energies that profoundly reshaped the nature of religion throughout the nineteenth century and beyond.

This shift in American Christianity provided a fertile environment for the Second Great Awakening (see CH #151). We can also trace the emergence of evangelical missionary societies back to the 1700s and the influence of Great Awakening theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758). He raised a new consciousness about the possibility of missions, both in his transatlantic correspondence and in published works such as Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God (1737), Humble Attempt to Promote . . . Union Among God’s People (1747), Life of David Brainerd (1749), and History of the Work of Redemption (published posthumously in 1774). His writings repeatedly focused on “the advancement of the kingdom of Christ” or “the propagation of the gospel.”

Of course Roman Catholics, Anglicans, and Pietists had already established missions over the previous two centuries. Decades before Edwards’s ministry, three new missionary societies addressed the needs of American colonists: the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (1698), the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (1701), and the Scottish Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (1709). Later efforts by Moravian Brethren Pietists and the Halle-Danish-English Mission in Tranquebar, India, to extend the gospel “to the uttermost parts of the earth” also provided an impetus for international Protestant missions.

From Edwards to Carey

Yet at every turn, we see lines connecting Edwards to the missionary spirit that emerged later. Edwards’s biography, Life of David Brainerd, touched the lives of laity, clergy, revivalists, and missionaries alike. Life tells the story of pioneer American missionary David Brainerd (1718–1747), who launched an adventurous ministry among Native Americans. The biography succeeded in raising missionary consciousness not only among Americans, but also among other English-speaking and German evangelicals. It inspired a veritable hall of fame of renowned evangelists: Melville Horne (c. 1761–1841), English missionary to Africa; Robert Morrison (1782–1834), Scottish missionary to China; Christian Friedrich Schwartz (1726–1798), German missionary to India; Samuel Marsden (1765–1838), English missionary to New Zealand; Adoniram Judson, American missionary to Burma; and the father of modern missions himself, William Carey (1761–1834), for whom the Brainerd biography “became a second Bible.”

Indeed Edwards’s effect on Carey is inestimable. Edwards’s Humble Attempt, which proposes a concert of prayer for extending the kingdom of Christ and hastening the millennium, influenced William Carey’s book, An Inquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens (1792), which ignited a passion for foreign missions among the English and led to the founding of the Baptist Missionary Society at Kettering.

Carey’s clarion call to spread the gospel also rippled throughout the United States, where the spiritual fervor and millennial expectations generated by the Second Great Awakening gave believers an energy unparalleled in American history. Worldwide, believers began duplicating Carey’s “society method” of missionary support and direction. The model took flight especially in the hundreds of voluntary societies and benevolent organizations that emerged in the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Transforming society

Amid the religious stir of the Second Great Awakening, the followers of Edwards, the so-called New Divinity men, refined and revised Edwards’s theology to support religious activism. Samuel Hopkins (1721–1803) took Edwards’s emphasis on loving God for who and what he is—without regard for what we receive—and transposed it into an ethic of “disinterested benevolence”—an obligation to help others irrespective of personal benefit. Embracing this theological rationale, hundreds of parachurch and voluntary organizations harnessed the spiritual energy of the Awakening into a massive effort to reform society, Christianize the nation, and extend evangelical faith around the world.

With budgets and influence rivaling the federal government, these societies exerted a powerful presence in American society. Their proliferation indicates an expanded view of the church, one that included not only the salvation of souls but the redemption of society. Christianity was seen as essential to the preservation of virtue, social order, and republican government. Voluntary societies filled the gap left by disestablishment.

Missions: At home and abroad

Some of the first societies focused on ministry in America. In 1796 New Divinity stalwart Nathanael Emmons (1745–1840) took the lead in organizing the Massachusetts Missionary Society, and others formed the New York Missionary Society. Two years later New Divinity men sponsored the Missionary Society of Connecticut. All three societies pledged to evangelize the “heathen” (including Native Americans) and the many New Englanders moving to western settlements.

It wasn’t long before the missionary spirit exploded farther outward and into foreign service as well, as simple gatherings like the Haystack Prayer Meeting turned into major societies.

The transformative model of the voluntary religious society or parachurch organization that emerged early in the nineteenth century remains a powerful shaping force even today, especially among American evangelicals. Parachurch ministries have proliferated since World War II, in some cases exceeding parallel ministries in major denominations, dwarfing their budgets, and competing for the loyalties of church members. Though not without their critics, these single-focused ministries continue to inspire and attract those dedicated to the goals of making disciples, alleviating suffering, addressing injustice, and spreading the gospel. CH

By David W. Kling

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #153 in 2024]

David W. Kling is Cooper Fellow and professor of American religious history and the history of Christianity at the University of Miami.Next articles

Azusa Street commentary and excerpts

The Azusa Street Revival won hearts amid criticism

Michael J. McClymond and others