Abandoned to God

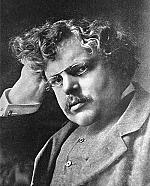

[Above: Detail from Oswald Chambers, Sitting with Book, 1906—Used with permission of the Oswald Chambers Publications Association, Ltd. / images courtesy of Wheaton Archives & Special Collections, Wheaton College, IL.]

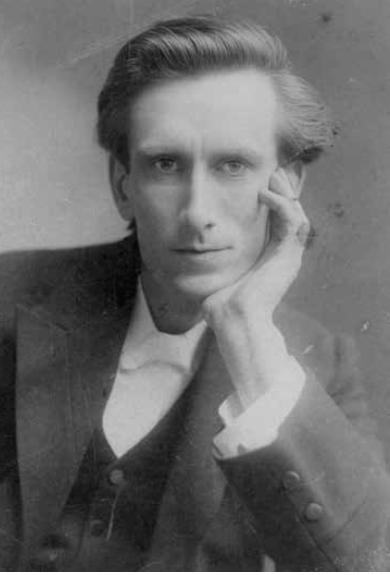

“He is the personification of the Sherlock Holmes of fiction,” a former student declared of Oswald Chambers (1874–1917), “tall, erect, virile, with clean-cut face, framing a pair of piercing bright eyes. One feels instinctively that here is a detective of the soul, one who has been in intimate fellowship with the unseen and can now speak with calm assurance of eternal things.”

To speak of eternal things was Chambers’s passion. He began to share as a teenager in his home church in London and continued through young manhood as a traveling “missioner” with the revival-oriented League of Prayer and as principal of the Bible Training College he organized with his wife. He continued into middle age as a YMCA chaplain to British Empire troops during World War I. And in ways that even the foresighted Chambers couldn’t imagine, he continues to speak of eternal things.

He was born in Aberdeen, Scotland, on July 24, 1874. The eighth of nine children (an older sister had died as a baby), Oswald grew up in the home of an intense Baptist preacher, Clarence Chambers (c. 1837–1925) and a sweet, saintly mother, Hannah (1840–1921). Both of his parents were baptized by famed British pastor Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834–1892), and the “Prince of Preachers” later prompted the 15-year-old Oswald’s conversion after his family’s move to London. Returning home from a Spurgeon service, the young man told his father that, given the opportunity, he would have dedicated his life to the Lord that evening. Clarence quickly replied, “You can do it now, my boy.”

“Then and there,” his brother Franklin recalled, Chambers “gave himself to God.” He was soon baptized and working in Rye Lane Baptist Church, which his family had joined. Chambers taught Sunday school and engaged in lodging-house work with “the down-and-out,” as a fellow worker recalled. “These men appealed to him, and perhaps gave him a deeper insight into the power of sin to degrade, and also the greater power of the grace of God to break the power of cancelled sin and redeem men to Himself.”

REDEEMING THE AESTHETIC KINGDOM

As a young man talented in poetry, music, and art, Chambers believed his life’s work would be “the redemption of the aesthetic kingdom . . . or rather the proving of Christ’s redemption of it” (see pp. 11–13). In his teens he attended art school, though he ultimately refused a scholarship to visit “the famous art centres abroad,” Franklin reported, “having seen men come back from their travels moral and physical wrecks.”

At 21 Chambers enrolled in the arts program at Edinburgh University in his native Scotland. The ancient university’s renowned professors challenged his intellect. But Alexander Whyte (1836–1921) of Free St. George’s Church, Scotland’s leading preacher at the time, nourished his spirit. Whyte expounded the Christian life to hundreds of young men after his Sunday evening services and taught them an appreciation for classic spiritual writings. Whyte’s passion for these works undoubtedly influenced Chambers, who would later call his own favorite books “silent, wealthy, loyal lovers.”

But Edinburgh also brought challenges: financial shortfalls created a stress that Chambers couldn’t ignore. By causing his freelance art projects to dry up, God nudged the young man away from the “aesthetic kingdom” and toward the preaching and teaching of Scripture. Chambers had once told a friend, “I shall never go into the ministry until God takes me by the scruff of the neck and throws me in.” But one day Chambers was “astounded” by another friend’s pious father, who looked him over and declared that he would be a minister. Suddenly Chambers could think of little else.

CALLED TO DUNOON

On an extinct volcano overlooking Edinburgh, Chambers devoted an evening to prayer. From this hill called Arthur’s Seat, he sensed a definite calling from God. In fact Chambers heard the Lord distinctly say, “I want you in My service—but I can do without you.” Unsure of what to do next, Chambers returned to his lodging. There he found a packet of information from a small theological training school in Dunoon, Scotland, 80 miles west on the Firth of Clyde.

The material had been sent anonymously, though it was later revealed that his father, after meeting the school’s principal, had mailed it. Whatever the case, Chambers was intrigued. He applied, was accepted, and spent nearly a decade in Dunoon as student, protégé, and friend of Rev. Duncan MacGregor (1842–1913).

A Baptist pastor who had led churches in England, Wales, and Chicago, Illinois, MacGregor was “noble, unselfish, and holy,” in Chambers’s estimation, possessing “character, character, character!” Old enough to be his father, MacGregor took on a fatherly role in the younger man’s life. “I never loved a man as I love him,” Chambers told a friend.

Though MacGregor also pastored Dunoon’s Baptist church at the time, his leadership of the Gospel Training College most powerfully affected Chambers’s life and ministry. Some 15 years after his death, Chambers’s widow, Biddy (pp. 15–16), wrote, “If [he] had been asked which were the most important years in his early life, unquestionably he would have replied, ‘The years at Dunoon.’” There, Chambers drank in MacGregor’s philosophy of ministry training, which featured personal, daily involvement in the learners’ lives. Chambers would later implement this idea in his own ministry at the Bible Training College in London (1911–1915) and among soldiers in the British military camps of Egypt (1915–1917).

LONG-HAIRED, SWEARIN’ PASTOR

But from early 1897 until late 1906, Dunoon was Chambers’s home base, training ground, and mission field. Upon Chambers’s arrival, MacGregor’s son Esdaile recalled, “he took a dominating position in the college and soon became marked as the most striking personality we had ever had as a student.” Noted both for his thin build and long hair, Chambers was often seen walking his dog on the hills surrounding Dunoon. He quickly began tutoring in the school and promoting arts in the community. And he filled the pulpits of nearby churches—to mixed reviews, due to his confrontational preaching style.

The younger MacGregor remembered Chamber’s “intensity and vehemence” (likely reflecting Clarence Chambers’s preaching), which “seemed to create a fear of God, in the sense of terror . . . rather than of confidence and love.” When the leaders of one church asked the school for pulpit supply, they specified, “Dinna send us yon lang-haired swearin’ parson.” Chambers mellowed after coming to know Dinsdale Young (1861–1938), an eminent Methodist preacher from Edinburgh who often visited Dunoon. It was Young’s example, Esdaile MacGregor suggested, that persuaded Chambers “there was work for him in preaching a simpler and friendlier gospel.”

A personal crisis, which Chambers described as “hell on earth,” undoubtedly also influenced that change in approach. Another prominent visitor to Dunoon was Dr. F. B. Meyer (1847–1929), pastor of London’s Christ Church, who spoke on the Holy Spirit. In his own words, Chambers “determined to have all that was going,” asking God “simply and definitely for the baptism of the Holy Spirit, whatever that meant.” For the next four years, Chambers’s communion with the Lord dried up, leaving only a sense of his own depravity. “Nothing but the overruling grace of God and the kindness of friends kept me out of an asylum,” he later said.

Ultimately Jesus’s words in Luke 11:13 changed everything for Chambers: “If ye then, being evil, know how to give good gifts unto your children: how much more shall your heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to them that ask him?” Chambers realized that he needed to claim the gift of the Spirit on the authority of Jesus, risking that “God will make it known to those who know you best how bad you are in heart.” But in desperation, he pressed on.

Though he felt “as dry and empty as ever,” Chambers preached at a meeting where 40 people came forward in response. Confused and afraid, Chambers quickly found Duncan MacGregor, who said, “Don’t you remember claiming the Holy Spirit as a gift on the word of Jesus, and that He said: ‘Ye shall receive power. . .’? This is the power from on high.”

Chambers finally realized his mistake. He had been trying to say, “Look what I have got by putting my all on the altar.” D. W. Lambert, who wrote a brief biography of Chambers 50 years after his death, quoted him saying, “The teaching that presents consecration as giving to God our gifts, our possessions, our comrades, is a profound error. These are all abandoned, and we give up for ever our right to ourselves.”

“RADIANT EMANCIPATION”

Oswald Chambers left no autobiography and rarely spoke of himself. But in one recorded testimony, he said, “When you know what God has done for you—the power and the tyranny of sin is gone, and the radiant, unspeakable emancipation of the indwelling Christ has come, and when you see men and women who should be princes and princesses with God bound up in a show of things—oh, you begin to understand what the apostle meant when he said he wished himself were accursed from Christ that men might be saved!”

With “the last aching abyss of the human heart . . . filled to overflowing with the love of God,” Chambers was ready for an even wider ministry. He would serve many years with the League of Prayer, traveling throughout Great Britain to urge Christians on to greater holiness. He would join a Japanese evangelist, Juji Nakada (1870–1939), for an around-the-world tour that led to an ongoing relationship with God’s Bible School in Cincinnati, Ohio. And he would marry Gertrude Hobbs (1884–1966), who would expand his ministry exponentially (see pp. 14–16).

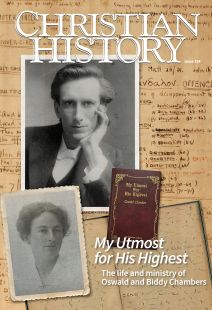

Chambers, who often bestowed nicknames on friends and acquaintances, called Gertrude “Biddy.” She established the ministry for which Chambers is most known today—“the work of the books,” in her words (see pp. 24–26).

As a teen Biddy had learned stenography, also known as shorthand—an abbreviated writing method that made it possible to record dictation efficiently. During their 18-month engagement, Chambers recognized the possibilities of marrying their skills for a “literary and itinerating work” for God.

It was a prophetic idea, though Oswald would see only a tiny fraction of its fulfillment. Biddy took shorthand notes of almost every lesson Chambers taught during their marriage, from May 1910 to his death in November 1917. She compiled a “wealth of notes,” especially from the Bible Training College they organized and oversaw for the five years leading up to the war, then during his teaching sessions with soldiers in the Egyptian desert (see pp. 18–20). In late summer 1917, Chambers reviewed printer’s proofs of Baffled to Fight Better, a study of Job that he and Biddy developed together.

Complications from an appendectomy soon ended Chambers’s earthly life at age 43. When God requisitioned “the O. C.” (a nickname and wordplay combining his initials and those of “officer in charge”), his ministry shifted fully to the printed page.

THE WORK CONTINUES

Within weeks of his death, a friend and coworker suggested creating a pamphlet of an article Oswald and Biddy had developed together on their honeymoon in New York state. Distributed to soldiers “far and wide” for Christmas, this teaching on Psalm 121:1–2 inaugurated a decades-long work of Chambers’s uniquely qualified widow. Biddy’s dedication—to God and to her husband’s teaching—would ultimately yield some four dozen books, most notably the daily devotional My Utmost for His Highest. With her help Chambers reached more people after death than he had in his extraordinary life.

“I think if I have an ambition,” he once said, “it is that I might have honourable mention in anyone’s personal relationship with our Lord Jesus Christ.” As he enjoys his second century in heaven, Oswald Chambers’s ambition continues to unfold on earth. CH

By Paul K. Muckley

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #154 in 2025]

Paul K. Muckley is the senior acquisitions editor at Barbour Publishing and author of Oswald Chambers: A Life in Pictures under the pseudonym Paul Kent.Next articles

“Music, Poetry, Art, through which God breathes”

Oswald Chambers desired to serve christ’s “aesthetic kingdom”

Kevin BelmonteServing God here and “Beyond”

Oswald and Biddy’s transformational ministry in Egypt

Annalise DeVries