God’s Bible School

[Above: God’s Bible School—Courtesy of God’s Bible School and College]

Though Chambers visited the United States multiple times, the only institution with which he maintained a long-term relationship was God’s Bible School (GBS) in Cincinnati, Ohio. He was introduced to GBS by Juji Nakada, cofounder of the Oriental Missionary Society (see pp. 33–36) and founder of the Tokyo Bible Institute (TBI), which was modeled after and supported by GBS. Both Nakada and Chambers were members of the Pentecostal League of Prayer, a UK radical holiness network founded by Richard Reader Harris (1847–1909). Chambers decided to travel with Nakada via the United States to Japan; together, they made stops throughout the States so Nakada could maintain contact with his supporters.

TRUE CHRISTIAN SOCIALISM

Already well known, Nakada served as warrantor for Chambers during the first contacts in the United States. In late December 1906, they arrived at GBS where Nakada was scheduled to speak and Chambers was drafted as a speaker at a convention and city mission meetings.

He was impressed with what he found at GBS. Women were prominent in leadership, the institution being far more egalitarian than most. Worship was vibrant. Faculty, staff, students, and volunteers ministered to the physical and social needs of the poor and marginalized of the city, while calling for personal and social transformation.

They addressed structural and exploitative sins of the city. They fed the hungry; they prayed for healing of the sick. They provided a rescue home for young women trafficked or otherwise engaged in the sex trade, giving them space and security to begin life anew. Resources, time, tears, and joys were shared; identities, including gender, class, race, regional origin, and denomination, did not limit service. GBS founder Martin Wells Knapp (1853–1901) had insisted that “accumulation of property for self is absolutely prohibited.” Chambers observed, “This is truly Christian socialism.”

Chambers was invited to “stay until July and teach and write some books.” He taught, receiving a $500 stipend that paid for his onward trip to Japan. Chambers’s first monographs were published, initially as a series of articles in the GBS Revivalist and subsequently as books by Revivalist Press. Chambers returned annually to GBS from 1907 to 1910, apologizing in 1911 that obligations at his London-based Bible Training College (modeled after GBS and TBI) made a visit impossible. But close contact with GBS continued. He contributed articles to the Revivalist for the rest of his life and received students at BTC recommended by GBS.

CRITIQUING AMERICAN CHRISTIANITY

Chambers was never a passive participant in life and spoke often of the need for informed critical thinking. While impressed by the enthusiastic worship at GBS, Chambers seems to have understood it as an American cultural expression of worship. He also noticed things in US radical holiness and Pentecostal networks and at GBS that he found concerning.

A kind critic who did not name names, he spoke against making any religious experience, whether conversion, entire sanctification, baptism of the Holy Spirit, glossolalia (speaking in tongues), or self-focused motive, including the desire to be “used by God,” the goal of religious commitment.

For Chambers religious experiences were not instant cures for the problems of human will; conformity to the will of God ought to be an ongoing daily project. This conviction, lived out in his own life, positioned Chambers as an ecumenical and effective evangelist to many.

By David Bundy

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #154 in 2025]

David Bundy is coeditor of Studies in the Holiness and Pentecostal Movements and interim director of the Manchester Wesley Research CentreNext articles

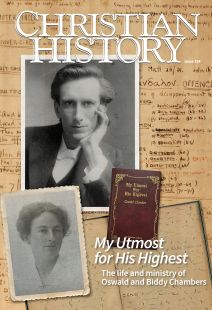

“Music, Poetry, Art, through which God breathes”

Oswald Chambers desired to serve christ’s “aesthetic kingdom”

Kevin BelmonteServing God here and “Beyond”

Oswald and Biddy’s transformational ministry in Egypt

Annalise DeVries