Authority, missions, and martyrdom

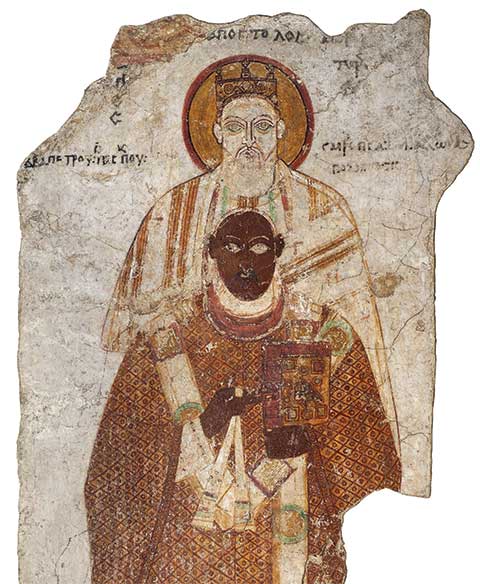

[Bishop Petros with Saint Peter, Faras. 974 to 997 AD. Tempera on Plaster—National Museum in Warsaw / Public domain, Wikimiedia]

Anyone who seeks an answer to the question “What happened to the apostles?” must admit in the end that the destinies of most of the apostles remain mysteries. Yet we have many clues and hopeful hints, but the seeker must review many different sources. One source, of course, is the Bible. Early church fathers provide other historically reliable sources of information. But many of our sources are apocryphal acts, accounts written by anonymous authors with fantastic imaginations (see pp. 14–16). Even these apocryphal acts, however, have some historical facts in their background.

Though little is certain about the apostles’ post-biblical lives, we can know what early Christians valued about the apostles—their apostolic authority, missions, and martyrdom. Our sources for the acts of the apostles, no matter how fanciful, repeatedly emphasize these three themes.

THE PRESTIGIOUS 13

We know that early in his earthly ministry, Jesus chose from his many followers 12 men to be his special disciples “so that they would be with Him and that He could send them out to preach, and to have authority to cast out the demons” (Mark 3:14–15). The number 12 made plain that Jesus was ushering in a new covenant people; these 12 disciples represented the 12 tribes of Israel. Often the biblical writers referred to this select group as simply “the Twelve” (Mark 3:16), but at other times, “disciples” (Matt. 10:1) or “apostles,” which means “sent-out ones, ambassadors, messengers” (Luke 6:13).

In the book of Acts, Luke, writing about the church after Jesus’s Resurrection, calls the Twelve mostly by their title, “apostles,” and the term takes on specific parameters and authority. In selecting a replacement for Judas Iscariot, Peter defines “apostle” as one who accompanied Jesus and the other disciples from the beginning, when John was baptizing, until the Ascension. This apostle would be “a witness with us of his resurrection” (Acts 1:21–22).

In the book of Acts, other than the listing of the 11 disciples who went to the Upper Room after Jesus’s Ascension, the author Luke does not mention any of the Twelve by name except for the inner three: Peter, John, and James. As a group, however, the apostles played an important role in the church. New believers were “devoting themselves to the apostles’ teaching” (Acts 2:42); “many wonders and signs were taking place through the apostles” (Acts 2:43); “with great power the apostles were giving testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus” (Acts 4:33). Furthermore the church recognized the authority of the apostles: those who gave their property to be distributed among the poor lay their gifts at the apostles’ feet (Acts 4:35); the apostles made administrative decisions about selecting the seven who would distribute the food fairly among the widows (Acts 6:6).

Outside the Twelve others earned the title “apostle,” chiefly Paul, the “Apostle to the Gentiles” (Acts 9:15, Rom. 1:5, Gal. 1:16, Eph. 3:8, 1 Tim. 2:7). Indeed some scholars, but not all, believe that God chose Paul, not Matthias, to be the twelfth apostle, replacing Judas (for an argument for Matthias, see p. 49). Other named apostles include Barnabas (Acts 14:14, 1 Cor. 9:5–6), James the brother of Jesus (Gal. 1:19), Andronicus, and Junia(s) (Rom. 16:7). Whatever the criteria by which these last four were considered apostles, however, the chief apostles in the Bible and the early church were the Twelve plus Paul.

These 13 apostles bore considerable authority in the early church. The Bible and church history portray them as evangelists, missionaries, and church planters throughout the known world. Their influence shaped the early church as they passed on the tradition that they had received from Jesus himself. As Paul said: “I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received” (1 Cor. 15:3). Jude spoke of “the faith which was once for all handed down to the saints” (Jude 3). The belief that the apostles were the source of the tradition—the rule of faith—that guided the church in belief and practice led to the doctrine and practice of apostolic succession.

According to this idea, the apostles received from the Lord Jesus true belief and practice and then passed on these traditions to their followers. From these followers the apostles ordained bishops, who not only taught the rule of faith but also ensured the orthodoxy of the churches they oversaw. Most ancient churches kept lists of bishops that linked them with the apostles, thus securing the so-called apostolic succession in the early church.

MIRACLES, MARTYRS, AND MISSIONS

The concept of apostolic succession elevated the prestige of the 13 apostles, including Paul. Subsequently churches gained status if they claimed that they were founded by apostles or were established near the apostles’ sites of martyrdom. Stories about the missions and martyrdoms of apostles proliferated, resulting in the varied, often fantastic apocryphal acts that provide many of our sources outside the Bible about the lives and ministries of the apostles.

The reader of these apocryphal acts of the apostles encounters the beheaded Paul, whose neck bled milk; Matthias, struck blind in a land of cannibals; and a variety of talking animals who accompanied Peter, Paul, Philip, and Thomas. Several apostles preached heretical messages of celibacy to married or engaged women. Furthermore the reader confronts contradictory stories: Matthew died by a spear in Ethiopia; in Parthia, he was burned to death, or was beheaded, or he died of natural causes (see pp. 39–41).

TO THE ENDS OF THE EARTH

Living up to the meaning of their titles, the apostles took seriously the commissions given by their Lord Jesus Christ, who told them to “go, therefore, and make disciples of all the nations” (Matthew 28:19) and to “be My witnesses both in Jerusalem and in all Judea, and Samaria, and as far as the remotest part of the earth” (Acts 1:8). According to sources such as Eusebius and Socrates Scholasticus (c. 380–c. 450), the apostles cast lots for the targets of their missions: Thomas was allotted Parthia; Andrew, Scythia; John, Asia Minor; Matthew, Ethiopia; Bartholomew, India; and Matthias, Myrmidon, “the country of the man-eaters.”

The apostles’ mission fields, however, were much more far-flung than these brief statements suggest. Thomas, once he finished his mission in Parthia (if he ever actually evangelized there), continued his southwestern sojourn toward India, which is the site of his best-known ministry.

Andrew was assigned by lots to evangelize Scythia, a region that now includes Ukraine and western Russia. St. Andrew’s Church in Kyiv, Ukraine, commemorates the northernmost point of the apostle’s travels in Scythia. Moving westward, Andrew reportedly ministered in Anatolia, or western Turkey. Andrew’s most famous mission took place in Achaia, southern Greece, where he died on an X-shaped cross.

John’s mission to Asia Minor, contemporary Turkey, is well documented in the book of Revelation, where we find him exiled on the island of Patmos, having overseen churches in Ephesus and the surrounding area. Less well known is a Latin legend about John reported by Tertullian in Against Heretics. During his persecution against Christians, Emperor Domitian had John brought to Rome. There Domitian attempted to execute John by plunging him into a cauldron of boiling oil (see p. 27). According to legend John survived, calling his ordeal an “invigorating bath.” After this failed execution, Domitian ordered John to his exile on Patmos.

Although Eusebius’s account indicates that Bartholomew evangelized India, various accounts place him also in Hierapolis, Turkey; Naidas, Parthia; Egypt; and Armenia. And the same can be said for other apostles, many of whom were reported to minister in multiple sites.

One of the more incredible stories about an apostle is the extravagant and yet persistent legend attached to James, the son of Zebedee, and his mission to Spain. There he is revered as “Santiago” (i.e., “Sant Iago,” that is “Saint James”), the national patron saint. All the literary sources that connect James to Spain are late, the earliest dating from the seventh century. According to these accounts, James evangelized Spain before being martyred in Jerusalem. His disciples carried his remains to Spain and buried them in Santiago de Compostela, which is a pilgrimage site to this day (see pp. 24–26). This story is widely doubted today, but it is an example of the kind of legends related to the apostles that arose in ancient times.

James is not the only apostle who traveled to the far west in the imagination of early Christians. According to Bishop Dorotheus of Tyre (255–362), Simon the Zealot traveled through Mauritania and other regions of Africa before he sailed to Britain, where he was crucified and buried.

LEARNING FROM LEGEND

Although this survey sketches only briefly the far-flung missions of several apostles, the sites of their evangelism clearly spread throughout the Roman Empire and beyond. From Spain and Britain in the west to India in the far east, with the Middle East, Europe, and Africa in between, the mission work of the apostles was impressive, even if only in early Christian imagination. One important lesson that we learn from the apocryphal acts is that evangelism and missions were imperative to early Christians, who envisioned their apostles as fulfilling the Great Commission to the uttermost parts of the earth.

Another significant feature of the apocryphal acts is the high value placed upon Christian suffering as a testimony to the truth of the gospel. In the biblical Acts of the Apostles, we see the disciples, who had cowered during Jesus’s Passion and death, take courage after his Resurrection (see pp. 6–9). When they were arrested for witnessing publicly to the lordship of Christ, they endured willingly the punishment administered by the Sanhedrin. In fact they rejoiced “that they had been considered worthy to suffer shame for His name” (Acts 5:41).

The apocryphal acts, whether trustworthy or fanciful, continued to emphasize the apostles’ willingness to suffer and even to die for Jesus Christ’s name. The beloved John was the only apostle without any story of martyrdom. His extended life was implied by Jesus in John 21, and most biblical scholars envision John as an old man when he was exiled to Patmos as he records in the book of Revelation. According to Jerome in Lives of Illustrious Men, John lived until the end of the first century and died of old age, 68 years after Jesus’s Passion.

Other than John, there are only two other apostles who possibly died of natural causes. Hippolytus, in On the Twelve Apostles, wrote that Matthew and Matthias “fell asleep,” the former in Hierees, Parthia (see pp. 39–41), and the latter in Jerusalem. Bishop Abdias of Babylon said of Matthias that he “slept a good sleep and rested from his labors in Judah” (see p. 48). To counter these vague suggestions of natural death, however, we have three separate accounts of Matthew’s martyrdom and four more about Matthias.

Sean McDowell, author of The Fate of the Apostles, concluded after his extensive research that, with the exception of John, all the apostles probably or plausibly died as martyrs. Despite conflicting answers and various accounts of their possible martyrdoms, that they all died faithful to the gospel of Jesus Christ remains the most certain fact. This is attested to by the church’s respect for the apostles as authorities and the many (if not all) traditions that relate their unfailing witness to the end.

Though we may not know exactly what happened to the apostles, those who composed and carried on their legacies emphasized the apostles’ passion for evangelism and missions as each of the Twelve shared Christ throughout the known world. They also made it clear that the apostles truly believed in Jesus as the risen God and Savior. Indeed, their faithfulness in the face of persecution and martyrdom adds to the proofs of Jesus’s Resurrection and his promise of eternal life to all who believe in him. CH

By Rex D. Butler

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #156 in 2025]

Rex D. Butler is recently retired as professor of church history and patristics at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary.Next articles

Sons of Alphaeus

Facts and myths About “brothers” Matthew and James, disciples of Jesus

Thomas G. Doughty Jr.“Doubting” or “daring” Thomas?

History’s most famous doubter recovered his faith and pioneered a bold mission to the East

Bryan M. Litfin