Altar without throne

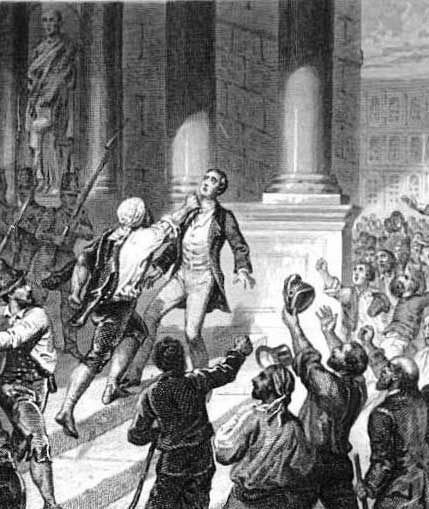

[Assassinat de Pellegrino Rossi (Rome, 15 novembre 1848). H. de Montaut - César Vimercati, Histoire de l'Italie en 1848-49, 7e édition, Paris, 1859 / Wikimedia]

The French Revolution brought the “throne and altar” alliance crumbling down. In July 1790 the revolutionary government created the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which denied the pope approval of bishops and democratized the process of selecting clergy. All French clergy were required to swear an oath supporting this new order. Pope Pius VI (r. 1775–99) condemned the legislation, accusing the French government of “arrogat[ing] to itself the power of the Church.”

Pious prisoners

During the Reign of Terror (1793–94), revolutionary violence erupted against the church. Many clergy and members of religious orders were beheaded as supporters of the old regime, including the 16 Carmelite sisters of Compiegne. An uprising against the revolutionary government, largely fueled by devout Catholics, was crushed with horrific brutality.

The revolutionary general Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) invaded Italy and captured Pius VI, who died in captivity. Later that same year, Napoleon seized power in France and pursued a more pacifying policy toward the church. But he also incorporated the Papal States into the French Empire in May 1809. For this act Pius VII (r. 1800–23) excommunicated Napoleon and his associates, invoking “the rights of the Church.” An angry Napoleon imprisoned this pope too, forcing him to sign a concordat (treaty) on Napoleon’s terms in 1813.

When Pius VII returned to Rome in 1814, he was determined to see the church restored in post-Napoleonic Europe. He and his successors Leo XII (r. 1823–29) and Gregory XVI (r. 1831–46) accomplished this by making concordats with European powers, just as they did before the revolution. But the restoration of throne and altar would prove short-lived.

Revolutions in Rome

In 1848 a new series of revolutions swept across Europe. In the Papal States, the revolution began with the assassination of Count Pellegrino Rossi (1787–1848), an economist appointed by Pius IX (r. 1846–78) to implement moderate reform. Revolutionaries then attacked the papal palace and forced the pope to agree to their demands. As an act of defiance, Pius IX declared, “But let Europe know that I am a prisoner here. I have no part in the [new] government; they shall rule in their own name, not in mine.” Several days later Pius secretly fled Rome.

The “Roman Republic” toppled after only five stormy months in 1849 due to a French invasion, and Pius IX returned to Rome in 1850. But the political temperature continued to rise. In 1859 to 1860, Italian nationalists managed to unify much of Italy and proclaimed the “Kingdom of Italy” in March 1861, with Rome as the official capital. Pius IX refused to abandon the long-standing “temporal authority” of the pope over the Papal States, and with French support he managed to hang on for another decade.

Meanwhile he issued the Syllabus of Errors in 1864, reflecting his conviction after 1848 that the pope could not “come to terms with progress, liberalism and modern civilization.” Among other things, the syllabus condemned the belief that “the civil power…[could] define what [were] the rights of the Church, and the limits within which she [could] exercise those rights.”

Days prior to this, Pius declared his intention to call an ecumenical council to address more fully the challenges the papacy faced. The convening of the First Vatican Council in 1869 coincided with the final stages of the fall of the Papal States. In September French troops finally withdrew from Italy due to the outbreak of war with Prussia and its German allies. Italian nationalist forces then marched into Rome, ending a thousand years of papal authority over central Italy and inaugurating a new era in which the altar would stand without the throne. CH

By Daniel T. L. Moore

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Daniel T. L. Moore, doctoral candidate at Liberty University