Winds of change

["Capture of Rome" B. Console, La Breccia di Porta Pia. 1870. Fratelli Treves Editori–Milan, 1895—Public domain, Wikimedia]

A severe thunderstorm rolled across Rome on a hot July day in 1870, darkening the massive dome of St. Peter’s Basilica. Inside, Pope Pius IX spoke above the rumbling, announcing that the council fathers had voted in favor of the decree defining papal infallibility. Some saw the dramatic weather as a sign of heaven’s judgment on the proceedings. But was it approval or condemnation?

Pius had called the world’s bishops together seven months earlier. Over 20 years into his record-setting 31-year papacy, he felt the ground shifting beneath him. His reputation had turned from liberal reformer to hidebound reactionary.

Two years after Pius’s election in 1846, his friend and papal government minister, Pellegrino Rossi, was assassinated in the streets. Perceiving the murder as a harbinger of civil disorder and revolution, Pius fled Rome and a short-lived “Roman Republic” was erected (p. 11). Disillusioned by these events and the anticlerical character of Europe’s liberal political movements, the pope turned against political reform and cultivated a vision of the church as a bulwark against the disintegration of the traditional order. Pius returned to Rome in 1850, where he enjoyed the tenuous protection of the French military, which kept the Italian revolutionaries at bay.

Many grumbled that the institution of the papacy, and perhaps the Catholic Church more generally, had outlived its utility. Successive blows from the Protestant Reformation, Enlightenment agnosticism, and political nationalism (see pp. 6–10) seemed to confirm that old-fashioned Catholic doctrines and customs were in a state of terminal decline.

In the face of these challenges, Pius issued his Syllabus of Errors in 1864, in which he rejected the idea that “the pope may and must reconcile with and adapt himself to, Progress, Liberalism, and Modern Civilization.” His terse syllabus contained references to other papal documents that offered fuller explanations of the propositions being condemned. But such details were largely lost in the ferment of the time. For many observers Pius appeared to be an incomprehensibly reactionary figure, opposed to inarguably good things such as “progress” and “democracy.”

A clarifying council

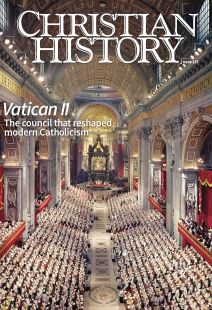

Seeking to clarify and reiterate the timeless truths of the faith and teachings of the church, Pius convened the twentieth (in Catholic reckoning) ecumenical council, the first since the Council of Trent had responded to the Protestant movements of the sixteenth century. Previous councils in Rome had been held at the pope’s cathedral, St. John Lateran. St. Peter’s Basilica on Vatican Hill would be the venue for this one, and so it became known as the Vatican Council. (The modifier “First” would be added later). In December 1869 some 700 bishops gathered at St. Peter’s.

The original agenda was broader than the dogmatic definition of papal infallibility for which the council would be most remembered. The first order of business was a response to the Enlightenment project and its philosophical offshoots. Across Europe in the seventeeth and eighteenth centuries, thinkers such as John Locke, Immanuel Kant, and Benedict Spinoza had subjected Christian history, Scripture, and doctrine to scientific scrutiny, concluding that much traditional belief lacked a rational basis (see CH #139). Many of these philosophers saw themselves as defending religion, separating the wheat of reasonable Christianity from the chaff of myth and superstition. Some Christian thinkers acceded to this approach but sought to wall off religion as a separate category of human experience—personal, emotional, private, and thus invulnerable to rational attack.

In contrast the council fathers in Rome refused to cede the ground of reason to the critics of traditional faith. They insisted that the human intellect was a God-given faculty that, properly employed, enhanced rather than denigrated religious belief. The harmony of faith and reason was evident in Scripture, and it was a hallmark of the Catholic intellectual tradition that had reached its peak in the magisterial writings of the thirteenth-century philosopher-theologian Thomas Aquinas (c. 1224–1274). The faith’s supernatural elements, including miracles such as the Resurrection of Christ, might exceed the capacity of reason to fully grasp or explain, but they did not contradict it.

On April 24, 1870, the council issued its Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith (Dei Filius), which condemned “that doctrine of rationalism or naturalism. . . . which spares no effort to bring it about that Christ . . . is shut out from the minds of people and the moral life of nations.” Against those who sought to sever faith and reason, the council asserted that “there is a twofold order of knowledge, distinct not only as regards its source, but also as regards its object.” “Even though faith is above reason,” it continued, “there can never be any real disagreement” between them, “because it is the same God who reveals the mysteries and infuses faith, and who has endowed the human mind with the light of reason.”

Deliberations on other items of discussion were more contentious. Those present agreed that the church itself was infallible on matters of faith and morals. This represented the classic Catholic understanding of Christ’s assurance, “I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Matt. 28:20, RSV)—that the Holy Spirit would protect the church from falling into error. Less consensus existed on precisely what role the bishop of Rome played and the meaning of papal infallibility. That the successor of Peter had primacy in the church was without question, but did he have supreme jurisdiction, and were his teachings certainly inerrant and irreformable? If so, under what conditions? Is the pope always speaking God’s binding truth, or are there times his pronouncements are not binding? Further complicating the theological questions was a prudential one: even if papal infallibility was genuine Catholic dogma, was it wise to emphasize it, given the current political conditions?

Infallibility, inopportunity, opposition

These considerations unfolded into three possible positions, each of them represented to some degree among the council fathers. Major figures from the numerically small but intellectually potent English Catholic Church exemplified the three perspectives: later life converts Cardinal Henry Manning (1808–1892) and Father John Henry Newman (1801–1890), and the prominent intellectual Lord John Acton (1834–1902). Manning was an “ultramontane” or “infallibilist,” enthusiastic about proclaiming the infallibility of the pope. Newman was an “inopportunist,” quietly affirming infallibility but believing that the question needed more study and the time was not yet ripe for a full-throated declaration. Historian Acton stridently opposed the doctrine, asserting that the historical record proved the opposite: popes had in fact been demonstrably mistaken on matters of doctrine. Another British observer colorfully reported that Vatican officials regarded Acton as “a devil in a holy-water font.”

Although Acton and others outside the council employed the press to create controversy around the deliberations, outright opponents of papal infallibility among the bishops themselves were few. Pius IX had himself exercised this prerogative by defining as dogma the doctrine of Mary’s Immaculate Conception in 1854, arousing little objection. Prior to promulgating the dogma, Pius had consulted bishops around the world regarding the sense of the lay faithful and appointed a panel of experts to examine the proposed doctrine’s history and theology. Far from being a raw exercise of power, the pronouncement of the Immaculate Conception was, in Pius’s estimation, simply the ratification of a teaching deeply rooted in the Christian tradition. The council’s approval of papal infallibility was not an inflation of papal power or an endorsement of papal opinion, but instead a recognition of the unique role of the successor of Peter as guarantor of theological orthodoxy.

A heavy majority of council fathers acknowledged this role. Thus, despite Acton’s maneuvering and the hesitation of the inopportunists, the pro-infallibility party carried the day, with the final vote passing almost unanimously, 533 to 2. In its first three chapters, the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church of Christ (Pastor Aeternus), circulated July 18, 1870, affirmed Catholic teaching regarding the pope’s primacy and jurisdiction. Regarding infallibility the key passage appeared at the end of the document’s final chapter:

We teach and define as a divinely revealed dogma that when the Roman pontiff speaks Ex Cathedra that is, when . . . in virtue of his supreme apostolic authority, he defines a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole church, he possesses, by the divine assistance promised to him in blessed Peter, that infallibility which the divine Redeemer willed his church to enjoy in defining doctrine concerning faith or morals. Therefore, such definitions of the Roman pontiff are of themselves, and not by the consent of the church, irreformable.

The official tally on Pastor Aeternus was misleading, though, because most anti-infallibilist bishops left Rome before the vote was taken. (A preliminary vote had shown substantial but not overwhelming support for the dogma: 451 in favor, 62 in favor “conditionally,” and 88 opposed.) The bishop of Little Rock, Arkansas, Edward Fitzgerald (1833–1907), was one of only two participants who stayed to register a no vote. One motivation for early departures was to avoid the uncomfortable experience of publicly opposing the pope, but danger offered another excuse: the pressure of the Franco-Prussian War had compelled the French to withdraw their garrison, and the forces of the Risorgimento (Italy’s revolutionary nationalist movement) were closing in on the Eternal City. Rome was no longer safe for churchmen.

Despite the declaration on infallibility, the papacy still appeared to be beleaguered. Believing that the church’s power had historically derived more from political clout than inherent spiritual merit, prominent American Unitarian minister Theodore Parker (1810–1860) wrote from Rome estimating papal influence in the wake of Italian unification: “When his temporal power is limited to this city, with 176,000 antiquated, good-natured people, his spiritual power will be worth little.” Opposition also persisted within the Catholic Church. Lord Acton’s historian-mentor, Father Ignaz Döllinger (1799–1890), joined a band of German-speaking Catholics in rejecting Vatican I. They formed a schismatic church known as Old Catholics, a small body that survives today.

Unfinished business

Yet most Catholics rallied around the pope. Even those opposed to or uncertain about infallibility—including Bishop Fitzgerald and Father Newman (who became a cardinal in 1879)—deferentially accepted the council’s decision. And though Pius protested the seizure of the Papal States to his dying day, by the late twentieth century, the dominant perspective had changed. John Paul II’s official biographer, George Weigel (b. 1951), contended that “the loss of the Papal States was a great boon to the papacy and to the church’s evangelical mission.” Freed from the burden of political rule, the pope could focus his attention on spiritual matters and emerge as a defender of universal moral values.

Benedict XV, for example, unencumbered by political alliances or military obligations, became the world’s foremost voice for peace during the bloody days of World War I. In 1950, when Pius XII, teaching ex cathedra, defined as dogma the bodily assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven at the end of her earthly life, little dissent existed in Catholic circles—much like the experience of his predecessor’s declaration concerning her Immaculate Conception.

Back in Rome in the summer of 1870, with the threat of armed conflict bearing down on the city, the council broke up the day after the vote on infallibility. But the meeting was never formally adjourned, so technically Vatican I was in a state of postponement until 1962. In that year the council fathers of Vatican II began by officially closing Vatican I. The Second Vatican Council was called in part to complete the “unfinished business” of the truncated earlier council. But by that time, almost 100 years later, four pontiffs had come and gone since Pius IX, and it was a different church in a different world. A new pope, along with a new generation of bishops, would respond in a new way to the challenges confronting the church. CH

By Kevin Schmiesing

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Kevin Schmiesing is an instructor of church history in the Catholic Archdiocese of Cincinnati’s Lay Ecclesial Ministry Program and cohost of the Catholic History Trek podcast.Next articles

Meeting the modern world

Vatican II’s call to action for the global Catholic Church

Nadia M. Lahutsky