Meeting the modern world

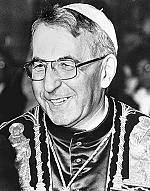

[Archbishop Marcel-Marie Dubois talking with cardinal Achille Liénart at the Second Vatican Council—Roman Catholic Diocese of Besançon / [CC BY-SA 4.0] Wikimedia]

When Angelo Roncalli, patriarch of Venice, was elected pope in October 1958, the cardinal electors intended him to be a caretaker—a maintainer of the status quo. But John XXIII had something else in mind. His announcement in late January 1959 that he was calling a council surprised everyone, not least the Roman Curia, the men charged with the Catholic Church’s administration and, likely, his cardinal electors. A council? Why? There were no pressing doctrinal heresies to oppose. The worldwide church was humming along just fine. Hadn’t Vatican I settled every question one could ever imagine with its firm definition of papal primacy and papal infallibility? But John XXIII’s big idea responded to a question he had asked himself in prayer: What can I do for Christian unity, beyond pray?

A cautious commission

The Curia dragged its feet over the next few years, although the preparatory work for John’s council did eventually get underway. Letters were sent to diocesan bishops and university leaders throughout the world informing them of the upcoming council and asking what issues they thought should be considered. Not everyone responded, and those who did proposed minor matters of pastoral concern. After all when was the last time Rome had asked them for an opinion? Opinions, that is, directives, usually went in the other direction. Nevertheless, the preparatory staff compiled the responses.

The “pre-preparatory” commission, largely filled with curial staffers or “safe” men—that is, none of the suspect theologians silenced under Pius XII (see pp. 17–20)—established 12 working commissions to draft documents (schemata) to present to the council fathers. These texts—in Latin—went out to all those invited in the summer of 1962, along with the admonition to read them and come ready to vote on them. They went also to ecumenical observers whose fraternal presence would be something new at a general council. A council inspired by the ideal of Christian unity could not proceed as though Christian communities beyond the Roman Catholic Church did not exist.

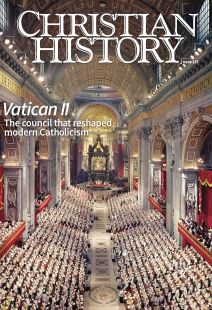

John XXIII opened Vatican II on October 11, 1962, with a solemn celebration of Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica, invoking the Holy Spirit. The pope’s opening address set the council’s tone. He urged the gathered bishops and heads of major religious orders to consider the “signs of the times,” to avoid being influenced by those “prophets of doom” who were always saying things were getting worse and worse, to aim for the “medicine of mercy” rather than that of judgment, and to pursue a council that would be pastoral in tone and effect. The church was, he said, in need of aggiornamento, a continual updating. True to Pope John’s vision, Vatican II would issue no anathemas, and it would make an effort, though halting in some aspects, to be in dialogue with the contemporary world.

Changing the tone

The hard work began the next day when Cardinal Liénart (Lille) rose to address—or protest, rather—the proposed vote on the men appointed to fill out the various council commissions: those who would receive the work of the discussions and redraft the texts. The 2,679 council fathers (1,044 from Europe, 956 from the Americas, 379 from Africa, and 300 from Asia) were largely unknown to each other and couldn’t possibly know whether the people on the lists were competent to do the work. A vote that day would have made Vatican II a rubber stamp of the Curia’s usual business without ever dealing with the real issues the church faced in the modern world.

The council fathers erupted in applause, and the moderators determined they should adjourn for several days. By this act the driving force of the council was set in motion—that the bishops would own the work of this event. This filled with joy those council fathers who had taken to heart Pope John’s message of hope; but it produced dread in those satisfied by the status quo (most curial officials and a powerful minority of bishops). All the remaining events of Vatican II can be seen through the lens of these different sides, sometimes called “progressive and conservative,” though competing opinions were far more complex than this simple distinction suggests.

Vatican II met from 1962 to 1965 during the autumn months, each daily meeting (called a congregation) creating an astounding number of logistical needs. Bishops found lodging as they could, often with seminaries that served their church. The meetings took place in Latin without simultaneous translation, which limited the number of voices heard from the floor. (Most bishops’ Latin skills did not extend to fluent oral communication.) The daily congregations met in the mornings after Mass, and the commissions’ work filled the afternoons. The council fathers met in language and regional groups developed on the first day of business to discuss the issues before them; they heard from many experts (called periti) in theology, canon law, ethics, church history, biblical studies, and so on, some of whom had accompanied particular bishops. With as many as 500 periti in Rome, one can imagine the cafes and trattorias filled with animated discussions about council matters!

Inviting the whole family

In the summer of 1962, when invitations went out to ecumenical observers—the Orthodox churches of the East and the Protestant communions in the West—many seasoned ecumenists received the letters with enthusiasm. Others, however, considered the overture with suspicion. Was this council going to be another “return to Rome” ploy? Moreover, Orthodox churches in some communist countries faced political reprisals if they attended, which inhibited Orthodox participation on top of their inherent objections to Roman claims of supremacy.

Nonetheless, 37 ecumenical observers did arrive, and, thanks to the efforts of Cardinal Augustin Bea (1881–1968), head of the newly created Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity, the ecumenical invitation was no mere formality or ploy. Observers received excellent seats near the table of moderators, as well as a translation system to understand proceedings. A testimony to the excitement and goodwill generated by the first session (1962), the number of attending ecumenists had grown to 105 by 1965.

The first session included precisely one layman, Jean Guitton (1901–1999), a personal friend of the pope, who sat with the ecumenical observers. Ten Catholic laymen, heads of international organizations, arrived in 1963. The final session included 29 laymen, 13 laywomen, and 10 Catholic sisters, all of them auditors. Their “listen-only” status speaks volumes about the role of laity and women at that time.

John XXIII’s death in June 1962 threw the future of the council into doubt. Moderates and reform-minded bishops received with relief the news of the election of Giovanni Montini, who, as Paul VI, quickly announced the date for the opening of the second session in September. These inevitable human moments, such as not only the pope’s death, but also President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, the conflict escalations in Vietnam, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and other ongoing tensions of the Cold War, could not but affect the participants.

“Full, conscious, and active”

Vatican II’s renewing spirit appeared in the debates of the first session, especially in the discussions on three important documents. The schema (draft text) on the liturgy contained major voices from the liturgical movement of the last 50 years, so this document reflected themes of renewal (see CH #129). Rather than a list of rules regarding the Mass, the schema exalted the presence of Christ in the church through the sacraments. The most-often quoted line from the final text, “The faithful should be led to take a full, conscious and active part in liturgical celebrations,” was a far cry from the pre-Vatican II experience of the Mass as a time for one’s private devotions and adoration of the Eucharistic elements.

The text also urged a renewed reverence for the Liturgy of the Word and a simplification of the rite of the Mass as well as of church décor, so as not to detract from the centrality of Christ. Further, local bishops could determine whether or not to extend the use of the vernacular in their parishes during worship. Finally approved in December 1963, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy changed the lives of Catholics every time they joined in a celebration of the Mass.

Dei Verbum

In mid-November the newly empowered council fathers took up the schema On the Sources of Revelation. Fierce objections arose to the schema’s presentation of revelation as propositional, subject to logic and syllogism, and to the document’s view that there are two sources of revelation (Scripture and tradition). No, someone responded, “There is only one source of revelation, the Word of God.”

Pope John used his authority to commit this text’s reworking to a joint group composed of the curial-dominated Theological Commission and the more reform-minded Cardinal Bea. Thus subsequent revisions of the text resulted in a view of revelation as personal, involving God reaching out to humans; all the faithful were urged to engage in serious study of the Bible employing critical methods. Dei Verbum (the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation), approved November 18, 1965, became an important basis for Catholic ecumenical dialogue, especially with Protestant churches.

Pope Paul's "black week”

The debates on the nature of the church covered three sessions and brought crises to the council. Council fathers had spent two months disagreeing with the curial-staffed commissions, and they pulled no punches in responding to the draft before them. “This document has in it nothing of the mystery that is the church.” “It ignores all matters of an ecumenical nature, such as who exactly is a member of Christ’s Church.” “It ignores all recent developments in theology.” “It’s too clericalist; there should be more attention to the Church as the People of God and its mission to humanity.” The objectionable description of the church presented in the first schema gave way over three council sessions to a deeper and more complex view of the church as communion in Christ, a communion that is lived out in history, the site not of perfection but of striving and—inevitably at times—failing in making effective Christian witness.

This communion ecclesiology (as it was called) led naturally to a view of bishops as in a collegial relationship with each other and with the bishop of Rome. Any such idea of an equalizing relationship among the clerical hierarchy, and especially the pope, could seem at odds with the century-old teaching of Vatican I. However, straw polls showed that roughly 2,000 of the council fathers approved of this emphasis. The other 500 or so were firmly opposed to any tinkering with the hierarchical view of the church. Paul VI deeply desired consensus.

On the heels of other fraught discussions on ecumenism and religious liberty, Pope Paul finally precipitated what many in the majority group called “black week.” On arrival into St. Peter’s on November 14, 1964, each council father received a folder containing a “preliminary explanatory note” to the text on the church. Given “by mandate of the supreme authority,” the note addressed the relationship between the bishops and the pope in a purely juridical fashion, occasionally repeating part of the text and often giving the exact wording from some of the minority bishops, specifically underlining papal authority.

Was Pope Paul offering a sop to the minority? Was he expressing his own fears? Was this document to be an interpretative key to the full text? Like John XXIII, Paul VI observed the council’s workings through closed-circuit television; unlike John, Paul became more inclined to intervene. This intervention did at the time seem an enormous setback; however, it did not ultimately undermine the power of the final version of Lumen Gentium (adopted November 21, 1964), with its rich view of the church as a mystery in which the pilgrim people, laity and clergy alike, live out their Christian witness.

Charity and liberty

Pope John had set in motion Vatican II with the goal of Christian unity through renewal. Although the council began with an eye to other Christians, implications also emerged for people of other faiths, and of none, those whom John had called “men of goodwill.” The Decree on Ecumenism reflected the spirit of Lumen Gentium in noting that all who have been justified by faith in Christ in baptism are incorporated into Christ. Protestants and Orthodox were separated brothers and sisters, no longer described as heretics and schismatics.

The text acknowledged that all parties bore some responsibility for historic divisions and called on Catholics to join with other Christians in common acts of service. Before Vatican II, ecumenical discussions took place outside of full Catholic involvement (such as in the World Council of Churches); after, bilateral dialogues emerged placing the Roman Catholic Church in dialogue with other world bodies: Orthodox, Lutheran, Reformed, Disciples of Christ, Methodist, and others.

The time was long since past when Christians could ignore the non-Christian world. The brief document Nostra Aetate (Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions), acknowledged the genuine search for God in other religions, urged Catholics to display charity in dealing with others and, significantly, explicitly disavowed the historical charge of deicide against the Jews.

But both the document on ecumenism and that on non-Christian religions required yet another text to be able to reach their full effect. The Declaration on Religious Liberty is arguably the most startling of all the developments of Vatican II. For several centuries the Catholic Church had taught that, being the one true faith, it must be granted freedom in civil society; whereas in areas where it was dominant, it was under no obligation to grant freedom of worship to others. This double standard made an understandable impediment to any authentic dialogue. Largely drafted by American Jesuit John Courtney Murray (1904–1967), the new document argued that human beings have an inherent dignity that requires they not be coerced in matters of faith and acknowledges the Catholic Church had not always lived up to its ideal.

Bishops from the United States, Europe, and communist-dominated countries supported this new reality, but those from Italy and Spain were frightened of changes this might entail. In the end the council overwhelmingly approved this text on December 7, 1965. That communal action provided an apt complement to Pope Paul’s October visit to New York where he addressed the United Nations, conveying the Catholic Church’s commitment to working for a more just and peaceful world.

Changed, but the same

On December 8, 1965, Vatican II, an extraordinary event of excitement, optimism, and hard work, was over. It endures now in the Christians affected by it and by the documents it produced. In some ways Vatican II changed nothing for Catholics. Each celebration of the Mass is still an encounter with Christ crucified and risen. The faith received from the apostles continues to be protected by a hierarchical structure.

In other ways Vatican II changed everything for Catholics. They now experience in Mass the ancient deposit of faith presented in their own language. Vatican II ushered in an explosion of new hymns and issued a clarion call to all Catholics to work for justice, often in concert with their Orthodox or Protestant neighbors. It unleashed and fed a hunger for Scripture studies. In short it continued the long process of the church’s timeless mission: bearing eternal truth within the messiness of history. CH

By Nadia M. Lahutsky

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Nadia M. Lahutsky is emerita associate professor of religion at Texas Christian University.Next articles

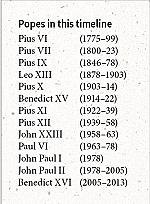

Christian History Timeline: Tracing Vatican II

Significant moments before, during, and after the historic council

the editorsAlways reforming, always the same

How popes interpreted Vatican II and helped reimagine the church

Barnaby Hughes