Always reforming, always the same

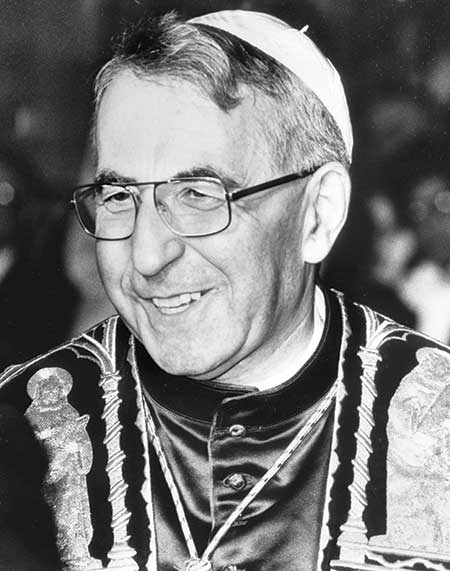

[Unknown photographer for Anefo, Pope John Paul I. September 19, 1978—National Archives, Netherlands / [CC0] Wikimedia]

It has often been said that the Catholic Church would never have an American pope. Yet on May 8, 2025, “the least American of the American cardinals,” Robert Prevost (b. 1955), was chosen to be the 267th bishop of Rome. Catholics worldwide immediately began scrutinizing the new Pope Leo XIV to see where he would stand on a whole host of issues. Traditionalist Catholics rejoiced as he appeared on the papal balcony following the conclave, wearing the heavily embroidered stole and mozetta (cape) that his predecessor, Francis, had eschewed. His chosen papal name reassured progressive Catholics—a name that evoked the Catholic social teaching of Leo XIII (r. 1878–1903) and promised that he would continue Pope Francis’s work of implementing the Second Vatican Council.

Different directions

Pope John XXIII had convoked the Second Vatican Council in 1962, and his successor Paul VI continued it upon his election in 1963. When he died in 1978, Pope John Paul I took both of their names to signal his commitment to the Second Vatican Council. And so did John Paul II, six weeks later.

But 27 years later at the death of John Paul II in 2005, Vatican II’s legacy stood at the center of the liturgy and culture wars in the Catholic Church. Instead of taking the name of his immediate predecessors, Benedict XVI sought to take the church in a somewhat different direction. His papal name evoked not only peacemaker Pope Benedict XV from the early twentieth century, but St. Benedict of Nursia (480–547), the patriarch of Western monasticism. His papacy marked a nuanced return to tradition, though that nuance was often lost on both his champions and his critics.

Benedict XVI spoke frequently of the hermeneutics of the council. (A hermeneutic is a theory or method of interpreting a text or event.) He favored a hermeneutic of continuity in contrast to the hermeneutic of discontinuity or disruption. There was to be no more talk of the “spirit of the council,” which could be used to justify almost any departure from tradition. Instead, the church needed to return to the sources and examine the documents of the council itself. For example, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy did not promote “active participation,” as if everyone must always be doing or saying something in worship, but “actual participation” (participatio actuosa), a phrase expansive enough to encompass silent prayer.

Another way Benedict sought to bring peace and revitalize tradition included his attempt to end the Lefebvrist Schism. Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre (1905–1991) had disagreed with many documents of the Second Vatican Council, such as the Declaration on Religious Liberty, which he saw as a reversal of Catholic doctrine. Most famously he rejected the reformed liturgy mandated by the council. His actions led to schism in 1988 when he ordained four bishops without a papal mandate. Pope Benedict XVI sought to heal that schism by lifting the excommunications of the four bishops and by giving wider permission for the celebration of the pre–Vatican II form of the liturgy. This latter move was meant not merely to be a return to tradition, but a “reform of the reform.”

Francis’s synods

Unfortunately Benedict’s actions failed to bring the Society of St. Pius X (founded by Lefebvre in 1970) back into the Catholic fold. And eventually Pope Francis (successor of Benedict whose name was inspired by the poverty, simplicity, and reforming ways of the Franciscans’ founder), in consultation with the bishops, placed new restrictions on the celebration of the preconciliar liturgy.

Under Francis the council took on new importance as he strove to consolidate its liturgical and other reforms. Francis’s wide-ranging reform of the Roman Curia placed evangelization at the center and gave laypeople more power of governance in the church, allowing them to hold high administrative offices for the first time.

However, synodality—a process of collaboration and discernment that brings together clergy and laity, especially laywomen—might have been his most significant initiative. This development grew organically from the episcopal collegiality that took root at the Second Vatican Council (see pp. 22–26). It showed first in the growing independence of many bishops who rejected the Curia’s conservative agenda. Second, it was seen in the delegation of much liturgical responsibility from the Curia to the bishops’ conferences. And third, it appeared in the creation of the Synod of Bishops, an advisory body to the pope independent of the Curia that would gather every three years.

Early in his papacy, Francis convened two contentious synods to address present pastoral challenges regarding marriage and families. Although many Catholics praised the synods’ efforts to address issues like divorce and homosexuality, conservatives felt that the pope had muddied the doctrinal waters. His later synods addressing young people and believers from the Amazon region of South America showed a promising path forward by incorporating more lay voices. Pope Francis’s Synod on Synodality (2023–2024) began at the parish level before successively broadening to the diocesan level, the national, and the continental—finally gathering clergy and laity in Rome for prayer, listening, and frank discussion. Yet Francis and others saw synodality as more than a mere reform of the Synod of Bishops; they thought synodality was a natural development of the call for renewal of Christ’s church at the Second Vatican Council in dialogue with the world.

The "medicine of mercy"

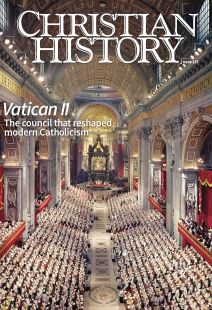

The church has convoked ecumenical councils somewhat regularly throughout its two-millennia-long history; these have mostly dealt with heresy, doctrine, and schism. Vatican II, though, sought to do something rather different: to engage the modern world positively and pastorally. But it is not quite accurate to say that the Second Vatican Council was only pastoral rather than doctrinal; it was clearly both. According to Pope John XXIII in his opening speech at the council, the church now prefers the “medicine of mercy rather than that of severity . . . by demonstrating the validity of her teaching rather than by condemnations.”

Longest and last of the conciliar documents approved by the bishops gathered at the Second Vatican Council, the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World is also the most ambitious. It is addressed not only to the church but to the “whole of humanity,” envisioning a dialogical relationship between the church and the world. The church and the world meant here, of course, are perhaps akin to St. Augustine’s city of God and city of man. The dialogue envisioned is primarily about seeking to understand the world to teach it. And so the document builds on Catholic social teaching, from the dignity of the human person to solidarity and the common good. The council did not go so far as to suggest that the church has as much to learn from the world as it does to teach the world.

This kind of dialogue, according to the Second Vatican Council, must characterize all the church’s relationships. Thus, in the Declaration on the Relationship of the Church to Non-Christian Religions, the church urges “dialogue and collaboration with the followers of other religions, carried out with prudence and love.” Dialogue is also mentioned in the Decree on Ecumenism: “From dialogue . . . will emerge still more clearly what the true posture of the Catholic Church is. In this way, too, we will better understand the attitude of our separated brethren and more aptly present our own belief.” Again, the church’s dialogue is described as an opportunity of learning so that it may teach more effectively.

This new emphasis on dialogue was not meant to preclude evangelization, which is well covered in the Decree on Missions. What was different and new, however, was the council’s expansive teaching on salvation outside the church. As expressed in the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church: “Those also can attain to salvation who through no fault of their own do not know the Gospel of Christ or His Church, yet sincerely seek God and moved by grace strive by their deeds to do His will as it is known to them through the dictates of conscience.” And yet the Decree on Ecumenism states that “it is through Christ’s Catholic Church alone, which is the all-embracing means of salvation, that the fullness of the means of salvation can be obtained.” In other words while salvation is possible outside Christ’s church, it always comes through or by means of the Catholic Church.

What does this look like, according to the council? The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church states: “This Church, constituted and organized in the world as a society, subsists in the Catholic Church, that is governed by the successor of Peter and by the bishops in union with that successor, although many elements of sanctification and of truth can be found outside of her visible structure.” This somewhat ambiguous phrase implies that the church Jesus Christ founded abides, remains, and continues in the Catholic Church, but is not exclusively identified with it. This dynamic conception of the church flows into the constitution’s next concept: the “People of God.”

Called to burn with the Spirit

People of God theology is biblical in origin and often rightly invoked to emphasize the laity as a corrective to clericalism. Yet it is much more expansive. According to the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, the “Catholic faithful as well as all who believe in Christ, and indeed the whole of mankind” belong to the People of God or “are related to it in various ways. . . . For all men are called to salvation by the grace of God.” This dogma also clarified how this teaching related to the Jews, expressing in the Declaration on Non-Christian Religions: “Although the Church is the new people of God, the Jews should not be presented as repudiated or cursed by God, as if such views followed from the holy Scriptures.” Though the Catholic Church does not include the Jews in the People of God as defined by the council, it considers Jews almost as Christians. The Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews forms part of the Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity rather than the Dicastery for Interreligious Dialogue.

If the theology of the People of God enthused the laity, they responded even more positively to the Second Vatican Council’s universal call to holiness. Laypeople knew that their priests are called to be holy and that monks and nuns spend their lives in pursuit of holiness, but many felt that it was out of reach for the average person. Not so, said the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church: “all the faithful of Christ of whatever rank or status are called to the fullness of the Christian life and to the perfection of charity; by this holiness as such a more human manner of living is promoted in this earthly society.” An unintended consequence of this democratization of holiness was that many monks and nuns abandoned their vows and returned to the lay state.

One further inspiration for the laity came with the Council’s Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity. Whereas prior to the Second Vatican Council, the laity were called to work for the mission of the church in concert with the clergy and under their guidance, now they were given greater autonomy to pursue their apostolate (their Christian work or calling) directly in union with Jesus Christ:

Since it is proper to the layman’s state in life for him to spend his days in the midst of the world and of secular transactions, he is called by God to burn with the spirit of Christ and to exercise his apostolate in the world as a kind of leaven.

Much of the groundwork for these teachings on the lay apostolate and the universal call to holiness were laid before the council by new ecclesial movements, and many more communities were formed after the council. Among these are Opus Dei, Cursillo, Focolare, the Neocatechumenal Way, Communion and Liberation, Chemin Neuf, Sant’Egidio, and Regnum Christi.

By opening up the Catholic Church to the modern world, encouraging dialogue with other religions and churches, and motivating greater involvement of the laity by calls to holiness, Vatican II undoubtedly changed the church. Some changes happened too quickly, while others did not happen fast enough; some were embraced enthusiastically, while others were virtually ignored. What is certain is that popes, bishops, priests, monks and nuns, laymen and laywomen will continue to argue about the council and how best to implement its vision for decades to come. Semper reformanda; semper eadem (the church is always reforming; it is always the same). CH

By Barnaby Hughes

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Barnaby Hughes is metadata editor at Atla, production editor of Atla Open Press, and editorial committee chair for Catholic Library World.Next articles

Reforming liturgy, learning, and law

Vatican II’s lasting effect on Catholic practice

Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt