“That they may be one”

[Based on "Cardinal Augustin Bea at a meeting 1963"—Ambrosius007 / [CC-BY-SA 3.0] Wikipedia

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CardinalBea.jpg ]

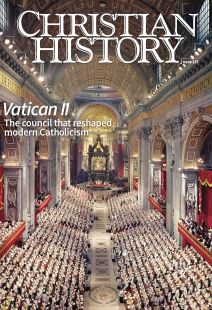

The Second Vatican Council easily ranks as one of the most significant religious events of modern history. It was groundbreaking in its intention to be an ecumenical council—not merely in the sense of involving the global Catholic Church, but in the theological sense of seeking unity among all Christians. An unprecedented vision in modern Catholicism, the council prompted significant theological reflection, brought about a notable shift in attitude toward Protestants and other non-Catholic Christians, and laid the groundwork for a new era of ecumenical engagement.

When John XXIII announced the council in 1959, he made clear that its purpose was not only to address internal reform but to promote Christian unity. To that end he established a Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity in 1960 to help guide the council’s work, appointing German Jesuit cardinal Augustin Bea to head it. Known for his biblical scholarship and openness to interconfessional dialogue, Bea quickly became one of the key figures in the council’s ecumenical efforts. In his opening address at the first session in 1962, the pope expressed a deep desire for “the unity of all Christians.” This marked a radical departure from the tone of earlier councils, especially the First Vatican Council, at which the proclamation of papal infallibility and the universal jurisdiction of the pope had further alienated many outside the Catholic fold, not least Protestants.

Openness to unity

By contrast Vatican II’s ecumenical orientation was reflected not only in words but also in its structure. For the first time in conciliar history, official observers from Protestant and Orthodox churches were invited to attend. Although they had no voting rights, their presence was not incidental. Many of these observers offered informal advice to the bishops and theologians and, in doing so, subtly shaped the substance and theological direction of the council. Their inclusion signified a genuine attempt on the part of the Catholic Church to listen to and learn from the broader Christian world, even as these visitors also learned from the Catholic Church.

Alongside Cardinal Bea, Dominican theologian Yves Congar played an especially significant ecumenical role. Congar, who had been marginalized for years by the Roman Curia due to his openness to Protestant and Eastern Orthodox theology, was nevertheless appointed by John XXIII as a peritus, or theological expert, to the council. He would go on to become one of its most influential theological voices. Decades earlier, Congar had written Chrétiens désunis: Principes d’un “œcuménisme” catholique (1937), translated into English as Divided Christendom: A Catholic Study of the Problem of Reunion (1939), a work that many regard as the magna carta of Catholic ecumenism. Congar’s reflections on the church, the laity, and Christian unity shaped several of the council’s key documents. He also left one of the most detailed diaries of the council.

Among the 16 documents produced by Vatican II, two stand out for their ecumenical significance: Lumen Gentium (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church) and Unitatis Redintegratio (Decree on Ecumenism). Congar had a hand in shaping both. Lumen Gentium redefined the nature of the church in more inclusive and nuanced terms. It famously declared that “the Church of Christ subsists in [subsistit in] the Catholic Church” rather than being synonymous with it. Though subtle, this phrasing represented a significant theological development: while affirming the Catholic Church’s fullness, it also acknowledged that genuine ecclesial elements exist outside its visible boundaries. The term subsistit in was a departure from the older, more exclusivist formula extra ecclesiam nulla salus (outside the church there is no salvation), and it opened the door to a broader and more charitable understanding of other Christian communities.

Even more direct in its ecumenical focus was Unitatis Redintegratio. This document recognized “separated brethren” as belonging to communities that the Spirit of Christ continues to use. It declared that “many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside the visible confines of the Catholic Church,” and it called for “dialogue,” “mutual understanding,” and joint prayer. One striking statement from it reads: “The separated Churches and communities . . . have been by no means deprived of significance and importance in the mystery of salvation. For the Spirit of Christ has not refrained from using them as means of salvation.” This marked a theological and rhetorical sea change. Protestants were no longer viewed as erring Christians or heretics to be corrected, but as fellow believers and participants in God’s salvific purposes for humanity.

Orbiting Christ

Protestant responses to Vatican II were diverse—shaped by denominational traditions, theological commitments, and broader ecclesial concerns. Some received the council’s developments with cautious optimism; others remained guarded. Switzerland’s Karl Barth (1886–1968), arguably the most important Protestant theologian of the twentieth century, did not attend Vatican II due to ill health, but he followed its proceedings closely. In 1966 he was able to visit Rome and afterward published a brief but important reflection on the council titled Ad Limina Apostolorum (1968). While remaining critical of certain features of Roman Catholicism—especially its hierarchical structure, doctrine of papal infallibility, and reliance on natural law reasoning—Barth welcomed the council’s renewed attention to Scripture and its openness to the modern world. He also saw in Vatican II a “wake-up call” for Protestant churches as well, encouraging them to pursue their own reforms.

Another Protestant theologian who offered a detailed and sympathetic response was Edmund Schlink (1903–1984), a German Lutheran and an official observer at the council. Schlink regarded Unitatis Redintegratio as a sincere and substantial invitation to ecumenical dialogue. He praised the council for acknowledging the ecclesial reality of non-Catholic churches and communities. In his reflections Schlink warned that “every church is in danger of understanding itself as the center around which the other churches are to revolve.” What was needed, he suggested, was a “Copernican revolution” in ecclesiology, in which Christ—not any single church—would be recognized as the true center.

In such a vision, each Christian community must see itself not as the measuring stick for others, but as one community among others being measured by Christ himself. Schlink called both Catholics and Protestants to a posture of mutual humility and charity, urging all churches to view themselves as co-orbiters around Christ rather than as rival centers of the faith. Along with his fellow Lutheran George Lindbeck (1923–2018) and others, Schlink went on to play an important role in postconciliar Lutheran-Catholic dialogue and in many other ecumenical efforts.

From a different Protestant perspective, American Reformed-evangelical theologian David Wells (b. 1939) offered a more cautious assessment in his 1972 book Revolution in Rome. Wells acknowledged the council’s “more irenic tone and ecumenical gestures” and its willingness to engage with modern concerns. But he also expressed theological reservations. He criticized Vatican II’s continued reliance on the magisterium and tradition alongside Scripture, which he saw as conflicting with the Protestant notion of sola scriptura (by Scripture alone). For Wells the council’s treatment of authority and doctrine was “theologically ambiguous and potentially unstable.” Nonetheless, he urged evangelicals not to dismiss the council, but to engage it in good faith, appreciatively but also critically.

Practicing what was preached

While Vatican II laid the foundation for a new ecumenical era, its implementation was sometimes uneven. Under Pope John Paul II (r. 1978–2005), the council’s ecumenical vision gained fresh momentum. A former council peritus, the Polish pope’s extensive travels, frequent meetings with Protestant leaders, and public gestures of reconciliation—including visiting Lutheran churches—earned him wide respect across denominational lines. In his 1995 encyclical Ut Unum Sint (That They May Be One), he doubled down on the ecumenical mandate of Vatican II, writing: “The Catholic Church is committed to the ecumenical movement and considers it one of her primary pastoral tasks.” He also expressed an openness to rethinking the exercise of the papal office so as to make it more acceptable to Protestants and other non-Catholics.

John Paul II’s emphasis on the “new evangelization” also resonated with many conservative Protestants. They saw in him an ally in resisting modern secularism, relativism, and moral decline. In this way the legacy of Vatican II—especially as embodied in John Paul II’s papacy—helped to create new partnerships across denominational lines, even if fuller theological agreement remained elusive.

Vatican II marked a decisive turning point in Catholic-Protestant relations. It helped to change the climate from confrontation to conversation, from mutual suspicion to mutual recognition. The presence of Protestant observers, the influence of theologians such as Bea and Congar, and the council’s own documents—especially Unitatis Redintegratio—contributed to breaking down walls of silence and hostility and opening doors to conversation. And yet, as many theologians have acknowledged, real differences remain. The central issues that divided the church at the time of the Reformation—justification, authority, sacramental theology, and ecclesiology—have not been fully resolved, at least not to the satisfaction of all Protestants. Some Protestants continue to worry that Catholic theology has not gone far enough in addressing the concerns of the Reformation, while some Catholics have expressed concern that ecumenical efforts might water down essential truths of the faith.

Still, as the council itself emphasized, ecumenism is not a matter of church etiquette or optional diplomacy—it flows from Scripture itself in the so-called High Priestly prayer of Christ “that they may all be one” (John 17:21). The legacy of Vatican II is thus both hopeful and unfinished, but its vision articulated in Unitatis Redintegratio continues to challenge Christians across traditions to seek truth in love, to embrace mutual understanding, and to pursue together the unity for which Christ prayed. CH

By Thomas Albert Howard

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Thomas Albert Howard is professor of humanities and history and holds the Duesenberg Chair in Christian Ethics at Valparaiso University. He is the author of The Faiths of Others: A History of Interreligious Dialogue and other books.Next articles

Reforming liturgy, learning, and law

Vatican II’s lasting effect on Catholic practice

Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt“The effect was electrifying”

How Vatican II influenced one Protestant denomination

Jennifer Woodruff Tait