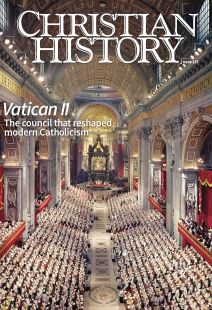

Reforming liturgy, learning, and law

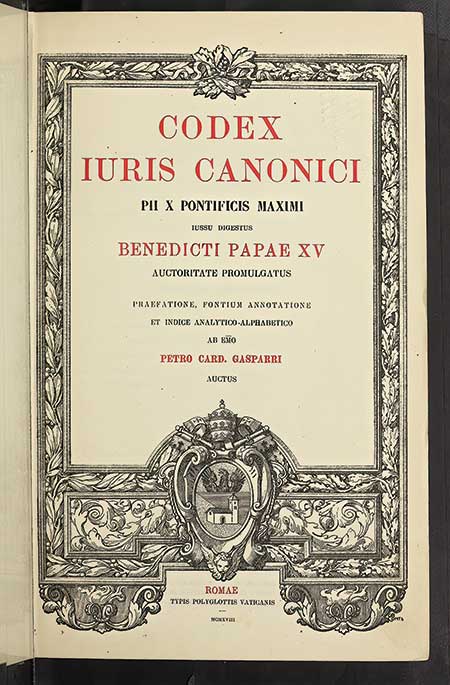

[Codex Iuris Canonici. Rome, 1918—University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign / Internet Archive]

John Henry Newman said that, just as Christ possessed the offices of priest, prophet, and king, “after His pattern, and in human measure, Holy Church has a triple office too.” For Newman the priestly office of the church is manifest in its liturgy, the prophetic office in its teaching, and the royal office in its governance. It is a measure of the Second Vatican Council’s significance that in its wake the Roman Catholic Church underwent dramatic change in all three of these areas, seen in the reformed rite of Mass (1969) and reformed rites for the other sacraments, the new Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992), and the revised Code of Canon Law (1983).

Living Liturgy

I once heard a potential convert to Catholicism ask a lifelong Catholic what Vatican II was, to which she replied, “that’s when they turned the altars around and we started having Mass in English.” The average Catholic churchgoer experienced the council as chiefly changing how the church exercises the priestly office through the worship of God.

The council itself prescribed relatively few specific liturgical changes but stated in its document on the liturgy (Sacrosanctum Concilium) the desire that “the rites be revised carefully in the light of sound tradition, and that they be given new vigor to meet the circumstances and needs of modern times.” This need for care in liturgical revision was paired with a sense of urgency: “The liturgical books are to be revised as soon as possible.” Reform details were left to a body called the Consilium that set to work on a comprehensive reform of all the liturgical books, but even before the council closed in 1965, changes began to appear: the most significant being the use of vernacular languages for the Scripture readings and the parts of the Mass that the laity were expected to say.

Along with the introduction of the vernacular, other changes quickly took place, such as the priest facing the people across the altar, rather than facing the same direction as the congregation with his back to them. The method of distributing Communion was also changed: people no longer knelt at an altar rail that stood between the altar and the congregation, but rather approached the altar in a line and received Communion while standing. Moreover the laity began to take on new roles formerly reserved for the ordained, such as proclaiming the Scriptures and helping distribute Holy Communion.

The net effect communicated a new sense of the nature of Catholic worship: not a sacred drama enacted by the priest to which the laity were expected to be devout observers, but rather a communal celebration in which the congregation’s role is as important as that of the priest.

In one sense this was not an innovation but a recovery of something very old. The prayers of the Mass itself, which date from the early centuries of the church, were almost always written in the plural, so that the priest was voicing the prayer of the people, not his own private prayer. But this truth had been obscured over time as fewer people understood the Latin of the prayers, and elements of the liturgy that had been spoken or sung by the congregation began to be taken over by clerics and choirs.

For several decades prior to the council, advocates of what was called the liturgical movement (see p. 43) had labored to recover the participation of the people in the Mass, encouraging them to sing the Latin chant and follow the Latin prayers in a vernacular translation. But the simple act of putting parts of the liturgy itself into the vernacular did more than any of these efforts had done to convey to people that the liturgy is something in which they are, as the council put it, “full, conscious, and active” participants.

These initial changes led to a cascade of others, some of them officially mandated, such as the simplification and streamlining of the rituals of the Mass, and others appearing by popular demand, such as the rise of the “folk Mass,” which replaced ancient chants with popular folk music and new compositions in a folk style. If you had told Catholics in 1960 that within a decade they would be singing along with guitars at Mass, they would have thought you had lost your mind.

And indeed some Catholics did think that the church had lost its mind—tossing out a centuries-old spiritual and artistic patrimony for a mess of puerile pottage. In the ensuing years, younger Catholics have reappropriated things abandoned as outdated by their post–Vatican II elders, showing increasing interest in more solemn ritual and ancient liturgical forms such as chant. But the general tenor of liturgical reform has now taken firm root in the church, such that even those who desire a more traditional liturgy still expect it to be one in which all are actively engaged in exercising the church’s priestly role.

Teaching for today

Though liturgical changes were the most obvious ones, the council’s official documents also displayed a significant change in the prophetic office of the church as teacher. In comparison with the statements of past councils, Vatican II documents are more positive and less juridical in tone. The council’s major pronouncements show the influence of the mid-twentieth-century theological movement known as ressourcement, which sought a renewal of Catholic theology by a “return to the sources” and an effort to state biblical truths in a way intelligible to modern people. Council participants believed church teachings ought to undergo “updating” (in Italian, aggiornamento, see “Did you know?”)—not by changing their substance, but by learning from modern philosophy and social sciences how to bring the church’s perennial faith to bear on modern concerns.

When the new catechism appeared in 1992, Pope John Paul II explicitly linked it to Vatican II’s approach to teaching, which he characterized as “not first of all to condemn the errors of the time, but above all to strive calmly to show the strength and beauty of the doctrine of the faith.” In pursuit of this, the catechism abandons the question-answer format typical of the genre, suggesting that is it less a collection of timeless statements to memorize and more a resource for reflecting on the truths of the faith. Like the documents of the council, it is replete with biblical and patristic quotations; it likewise seeks to speak to modern people, discussing not only the articles of the creed and the sacraments, but also such pressing modern issues as war, justice, sexuality, and economics.

This has made the catechism something of a “living document,” revised on occasion as the church responds to ongoing developments. (Most recently, Pope Francis revised the section on the death penalty to state the church’s opposition to it more strongly.) The catechism also presents itself as a resource from which more local catechisms, tailored to particular cultural sensibilities, might be developed. This too reflects the council’s emphasis on the need for the church’s prophetic office to be exercised in ways attentive to specific circumstances.

“Newness in fidelity”

The church’s third area of change after Vatican II came in revision of its governance. Church law had for centuries existed as a rather messy amalgam of pronouncements and rules; but in 1917 the church produced a unified Code of Canon Law, which governed the church until 1983, when a new code was produced. As with the catechism, John Paul II linked this revised code to Vatican II, calling it “a great effort to translate . . . the conciliar ecclesiology into canonical language.” He noted that not only its contents but also its actual method of production reflected the council’s “collegial” approach to the church.

Rather than a law handed down from above, the 1983 code grew from wide consultation with the bishops of the church, “so that . . . by a method as far as possible collegial, there should gradually mature the juridical formulas which would later serve for the use of the entire Church.” Moreover the goal of canon law was now understood not as simply obedience or conformity, but “rather to create such an order in the ecclesial society that, while assigning the primacy to faith, grace, and the charisms, it at the same time renders easier their organic development in the life both of the ecclesial society and of the individual persons who belong to it.”

The code itself reflects Vatican II’s emphases: the church as the “People of God,” the nature of authority as service, the universal church as constituted by a “communion” of local churches, the rights and duties of the laity, and ecumenism. Like the council, it seeks, as John Paul puts it, “fidelity in newness and . . . newness in fidelity,” and part of this newness is the way in which the royal office of the church is exercised in a less monarchical manner.

For example, the code allows local assemblies of bishops, such as the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, to issue “complementary norms” that address specific needs of their geographic area. This less centralized approach to unity serves the overarching principle expressed in the final canon of the code: “the salvation of souls, which must always be the supreme law in the Church, is to be kept before one’s eyes.”

The Second Vatican Council, though it ended over half a century ago, is an event whose effects still reverberate through the Roman Catholic Church. They reverberate not least in how the reformed liturgy, catechism, and Code of Canon Law continue to shape the ways the church lives out its priestly, prophetic, and royal identities. CH

By Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt is professor of theology at Loyola University Maryland, permanent deacon of the Archdiocese of Baltimore, and author and editor of books on Catholic theology.Next articles

“The effect was electrifying”

How Vatican II influenced one Protestant denomination

Jennifer Woodruff TaitReformers of Rome

Some Catholic leaders who influenced Vatican II

Jennifer A. Boardman and Edward Woodruff Tait