“The effect was electrifying”

[Order of St. Luke on Feast of St. Luke, 2023. St. Paul of the Cross Passionist Monastery in Pittsburgh, PA—Photo: Rev. Dr. Scot C. Bontrager, OSL. Used by permission]

In 1946 a Methodist pastor and ecumenically minded magazine editor, Romey Pitt Marshall (1901–1985), gathered a few like-minded pastors and founded something unusual for 1940s Methodism—a group that sought not only to “promote the public worship of the church” but to “magnify the sacraments.”

The group named themselves the Brotherhood of St. Luke (changed to “Order” in 1948—O.S.L.). Its first “rule of life and service” included the timid proviso that “insofar as possible we will wear recognizable clerical garb when engaged in the business of the church, and will wear at least a pulpit gown in morning worship and sacramental services.” (They soon relaxed the garb rule, said Marshall, “because of the very great prejudice in some quarters against anything that seemed in the least ‘Catholic.’”)

Handwriting on the wall

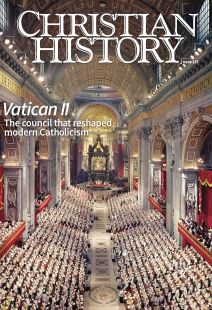

Despite being a minority voice within Methodism, the order was not alone ecumenically. Many Protestants, inspired by the changes among Roman Catholics (see CH #129), desired new approaches to worship. However, it took the fire of Vatican II to light the spark that transformed the worship of many mainline denominations. O.S.L. was primed for change, but even they could not imagine how great the change would be. Leader Hoyt Hickman (1927–2016) wrote of the moment he and Marshall knew nothing would ever be the same:

[Marshall] shared with me his enthusiasm for the liturgical renewal that was taking place in the Roman Catholic Church and his hopes for the Second Vatican Council then in progress. He had spent considerable time at a Benedictine abbey and become acquainted with progressive Catholic thinking. . . . That summer . . . he invited me to join him . . . for the 1964 convocation of the Liturgical Conference. There, with about 9,000 persons in attendance, the first version of the Mass in English translation was celebrated. . . .

The effect on me was electrifying. I saw the handwriting on the wall, not only for the Latin Mass, but also for the prevailing style of worship in Anglican and more formal Protestant churches. Prayerbook English as we had known it would go the way of Latin. Liturgical music and other arts would be radically changed. The newly-authorized Methodist Hymnal and Book of Worship would be out of date the day they were published. A whole new process of liturgical reform was needed—one that would combine our expanded knowledge of ecumenical liturgical history and theology with a freedom to use whatever language or art form most fully expressed the faith of the Church of all times.. . .

Hickman and theology professor James F. White (1932–2004), who almost single-handedly produced an entire bibliography on how worship must change in light of Vatican II, both became part of the UMC’s Alternate Rituals Committee in 1970; this group’s work ultimately produced the 1989 Hymnal and 1992 Book of Worship for the United Methodist Church.

These worship resources completely overhauled the way Methodists had experienced Sunday worship and sacramental services for the last 200 years. Gone were Sunday services based on a revivalistic frontier pattern and Communion liturgies deriving, through John Wesley, from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England. In their place, Methodists’ new official liturgies, like Catholic liturgies after Vatican II, drew on early church and ecumenical patterns to emphasize community and relevance over formality and reverence (see pp. 42–43). These liturgies, as well as some social justice motivations behind them, met with mixed reactions and backlash. The movement’s most lasting legacy was that United Methodists largely began to celebrate Holy Communion monthly rather than quarterly.

Today O.S.L. is an ecumenical religious order with an abbot, priors, life-vowed members, and its own monastic habit. United Methodism split in 2022; while post–Vatican II liturgical reform was not a leading reason for the split, its fault lines often cut between those who had welcomed the reforms and those who had resisted them. The effect was as electrifying as Hickman had foreseen; as in many other places, it was also more divisive than he ever imagined.

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait, senior editor of Christian HistoryNext articles

Reformers of Rome

Some Catholic leaders who influenced Vatican II

Jennifer A. Boardman and Edward Woodruff TaitRecommended resources: Vatican II

Learn more about the Second Vatican Council with these resources written and recommended by our authors and editors.

the editors and authors