Text turmoil

[Walter M. Abbott, S.J., Ed. The Documents of Vatican II. Herder and Herder Association Press, 1966—Amazon]

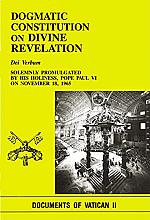

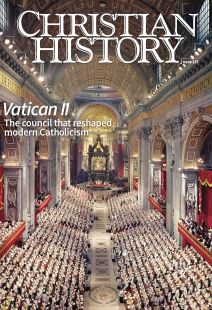

The debates that unfolded in the Second Vatican Council are sometimes lost while studying its teachings. Anyone can look up the final documents on the Vatican’s website or find any number of excellent printed editions of the texts, but this belies just how contentious the proceedings were. Two documents best illustrate the steps that ultimately produced all of the final texts: Dei Verbum (DV) and Dignitatis Humanae (DH).

Contested constitutions

Word of God, the shortest constitution issued by the council, was by far the most controversial and underwent the most revision. The original draft text (schema), called De Fontibus, does address the concept of divine revelation, as DV later would, but its style and scope is considerably different from the version the council would eventually issue. In fact DV generated enough passionate debate that it required two direct papal interventions.

Its original title reveals the reason for criticism: On the Sources of Revelation. This proposed document defended the view that Scripture is inerrant and is one of two sources of revelation, the other being tradition (see p. 24). Some council fathers criticized it for its scholastic language and, though it defended dogmatic truth, it had little to say about the doctrine’s spiritual purpose for ordinary Christians. Critics also argued that the document did not account for modern biblical scholarship and was unnecessarily divisive between Catholics and Protestants.

Content remained hotly contested until John XXIII removed the schema from the council’s proceedings in 1963. When it resurfaced later, it would take the direct intervention of Paul VI to settle a question about the nature of divine inspiration. The final document speaks not of separate revelation sources but of one “Word of God” that comes in many ways. This stresses the centrality of Scripture as revelation for salvation, but it also affirms that Scripture is not the only means by which the church receives divine revelation. DV was the last constitution to be approved in the final session in late 1965. Even though the discussion was fraught with strong opinions on either side, the final text received nearly unanimous approval (over 2,000 for, 27 opposed).

Does Error Have Rights After all?

The Declaration on Religious Liberty (Dignitatis Humanae, or DH) took a similar route to its final form. No separate document treated the issue of religious liberty, and initially, it was proposed as a section of Lumen Gentium. After over 400 amendments to this short document, it became its own text.

Because it wrestles with the particularly modern consideration of the right to religious freedom, the council had many questions about how this text would maintain continuity with previous papal and conciliar pronouncements. Historically the Catholic Church believed the state should uphold right religion and discourage (or prohibit) false religious practices, without forcibly converting anyone. Before Vatican II many condemned proposals for complete religious neutrality on the part of the state as “indifferentism,” repeating the slogan, “error has no rights.”

The council’s final draft of DH proclaims that all human beings have a basic right to religious freedom rooted in human dignity as created by God and a right to seek truth freely and express it to others, even if they err. An official spokesman for DH explained how to interpret key passages in the text, a practice that was necessary to settle some of the debates and smooth the voting procedures.

Liberty and Latin

Sixty years later, debates continue about all the documents and their interpretations. With respect to Dei Verbum, Paul VI’s intervention on the nature and limits of divine inspiration did not settle everything. Scholars still disagree about the Latin grammar of that intervention and, consequently, about the nature and limits of divine inspiration. And increasingly scholars question the official narrative surrounding Dignitatis Humanae and prior magisterial statements about religious liberty.

These two specific debates are very different: DV deals with finer details while DH’s interpretation has more serious implications. But each case shows that, even within Catholic theological contexts, official documents of the highest level (an ecumenical council!) do not simply end debates. They require interpretation, implementation, and continued reflection and teaching on the part of the church’s official teaching body.

By Luke Arredondo

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Luke Arredondo, executive director of St. Brendan Center for Evangelization and Spirituality in Pensacola, FLNext articles

Christian History Timeline: Tracing Vatican II

Significant moments before, during, and after the historic council

the editorsAlways reforming, always the same

How popes interpreted Vatican II and helped reimagine the church

Barnaby Hughes