Only Christ is king

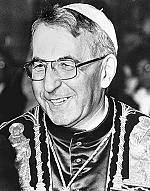

[Pius XII with tabard, by Michael Pitcairn, 1951 (retouched) —Postimages; Modifications by Donrdg54 /public domain, Wikimedia; The country of origin of this photograph is Italy. It is in the public domain there because its copyright term has expired.]

In 1925 Pope Pius XI established the Feast of Christ the King. After the brutal First World War, he believed Europe needed to remember its Christian heritage. Only by returning to God and Christ the King’s peaceful reign could they avoid further destruction. While his encyclical was for all, Pius XI specifically had enemies on the Left in mind.

Yet the next 20 years revealed that not every enemy of the church’s enemies was a friend. One crucial development in the decades leading up to Vatican II was the church’s experience with fascism. Wrestling with and ultimately rejecting this anti-Christian ideology laid the groundwork for the council’s wide-scale embrace of democracy, human rights, religious freedom, and friendship with the Jews and other non-Christians.

“With Burning Anxiety”

Pius XI thundered against atheist communism, which he considered Christian civilization’s primary enemy. Nevertheless, he correctly discerned godlessness on the Right. For instance he condemned the far-Right French movement Action Française which enraged many traditional Catholics. Its leader, the proudly anti-Semitic Charles Maurras (1868–1952), was an unbeliever who used Catholicism as a means to a civilizational end. Pius XI and many others found such instrumentalization of the faith unacceptable; herein, the pope thought, lay the fundamental deception of Christians embracing fascism. From the beginning among Hitler’s Nazis and Mussolini’s Blackshirts, Christianity was weaponized or tolerated only insofar as it could serve Hitler’s ends.

Unfortunately Pius was slow to appreciate the threat of Mussolini. His attempts to bargain with “Il Duce” inadvertently hastened Mussolini’s rise to power, and the pope stayed silent when Mussolini illegally and brutally invaded Ethiopia. Pius found his voice against fascism, however—and it was loud and righteously angry when he did. In the spring of 1937, church agents smuggled into Germany thousands of copies of an encyclical titled Mit Brennender Sorge (With Burning Anxiety—drafted in German rather than the traditional Latin). Read from every Catholic pulpit in the Reich on Palm Sunday, 1937, Pius XI’s words denounced Nazi violation of the concordat (bilateral agreement) with the Vatican, coupling this with criticism of Nazi racial doctrine. Furious, Hitler and Joseph Goebbels increased persecution of resistant Catholics immediately.

Though unfortunately veiled in his criticism of Nazi anti-Semitism, Pius began to see racism as a serious modern heresy. An encyclical denouncing racism was drawn up, but Pius XI died, and this “lost encyclical” (titled The Unity of the Human Race) was never published.

Pius XI’s successor, Pius XII (Eugenio Pacelli, r. 1939–58) left a complicated legacy in the face of Nazism and the Holocaust in particular. Though limited by his prejudices and diplomatic perspective, Pius XII still saved hundreds of Jews from almost certain death and helped facilitate resistance to Hitler. The times he lived in, however, called for a prophetic heroism he did not possess.

Vatican II's antifascists

Even so, papal leadership in response to fascism helped shape Vatican II. After Pius XI condemned Action Française, a young French intellectual named Jacques Maritain (1882–1973) ended his affiliation with the far-Right (see pp. 45–49), later becoming a great influence on many leaders at Vatican II, such as Pope Paul VI. Undoubtedly the world wars and fascist oppression profoundly shaped modern Catholic theology, social teaching, and political theory.

By Shaun Blanchard

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Shaun Blanchard, lecturer in theology at Notre Dame AustraliaNext articles

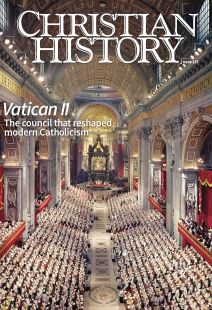

Meeting the modern world

Vatican II’s call to action for the global Catholic Church

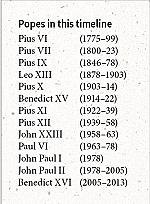

Nadia M. LahutskyChristian History Timeline: Tracing Vatican II

Significant moments before, during, and after the historic council

the editorsAlways reforming, always the same

How popes interpreted Vatican II and helped reimagine the church

Barnaby Hughes