Editor's note: George Mueller

I HAVE A FRIEND WHO PRAYS for toilet paper.

About 20 years ago, after we both graduated from seminary together, I went home to take up a pastorate in an established denomination. He set out to found his own ministry. Equipped with a little money, a business plan, and a lot of prayer, he said that his test for whether he was doing God’s will or not would be that he wasn’t going to buy toilet paper. People would give him toilet paper in answer to his prayers.

This concept was mysterious to me as a member of a church that always sent off missionaries and entrepreneurs with pre-arranged salaries. But off he went, and 20 years later he is still in ministry and—as far as I know—has never bought toilet paper.

I asked him once where he got this idea.

“George Müller,” he said.

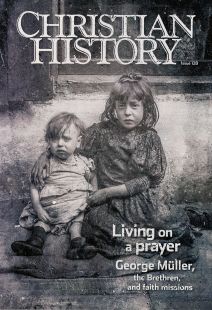

That was my first introduction to the ministry of Müller, a nineteenth-century preacher, author, and orphan home director. He came from Prussia (modern Germany), settled in England, and devoted himself to a life of faithful prayer. He founded The Scriptural Knowledge Institution and then a group of orphan homes; both were intended to help those whom others had forgotten, but even more than that, they were intended to demonstrate that God is always faithful.

Asking only God

Müller didn’t make budgets and speak to people about how much money he needed to carry out his plans; he didn’t have a board of missions that issued him funds; he didn’t send out letters begging others to supply his needs. He knelt in his house in Bristol with his wife and a few close friends and prayed—and people brought him money, bread, potatoes, clothes, apples, furniture, and just about everything else you can think of.

Müller didn’t come up with this idea on his own; he was deeply involved with a group of people who were dissatisfied with the church of their day. First meeting together in Dublin, Ireland—although they became more famously associated with the city of Plymouth in England—they didn’t like the close ties between the Anglican Church and the English state. They wanted to meet together without the artificial divisions introduced by denominationalism, and they wanted to seek the pure unity of the New Testament church.

This group refused to take on a denominational name, calling themselves only “Brethren.” (Today, in the United States, we usually call them Plymouth Brethren to distinguish them from the Anabaptist group called the Church of the Brethren.) Their influence was long-lasting, reaching out to touch such familiar figures as Amy Carmichael and Hudson Taylor in the nineteenth century and F. F. Bruce and Jim Elliot in the twentieth. And they bequeathed beliefs about how to read the Bible, follow God’s will, raise money for the Kingdom, and interpret the signs of Jesus’s Second Coming that have reverberated through evangelicalism for almost 200 years.

God’s joke was on me, because a few years after my friend went off to found his ministry, I met—and eventually married—a man whose family ran their small publishing ministry on Müllerite principles. Also, although not Brethren himself, he had spent time in mission in Romania with the group. The concept is still challenging to me, but it isn’t mysterious anymore. “Nine-tenths of the difficulties are overcome when our hearts are ready to do the Lord’s will, whatever it may be,” Müller once said. Indeed. It’s a lesson I am still learning daily. C H

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #128 in 2018]

Managing editor Christian HistoryNext articles

Nothing but the blood of Jesus

Müller speaks of his conversion when he was a divinity student at the University of Halle.

George Müller