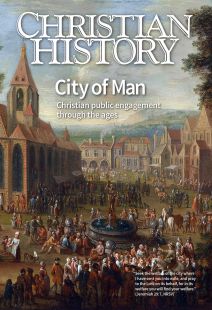

God rules over the cosmos

[Above: Patricq Kroon, Kuyper as the Pied Piper of Hamelin, 1900 to 1920—Rijksmuseum / [CC0] Wikimedia]

“There’s not a square inch in the whole domain of human existence over which Christ, who is Lord over all, does not exclaim, ‘Mine!’” In his inaugural address at the founding of the Free University of Amsterdam, Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920) declared these words, now among his most famous.

Kuyper argued that Christianity isn’t just about church, prayer, and daily devotions, but lays claim to every discipline—from art to astronomy, philosophy to politics—taught at the Free University. Why? Because Christ rules over every domain of created reality. Not only does this statement encapsulate Kuyper’s vision for this new Christian university in the Reformed tradition, but it also gets to the heart of his own life.

A man of deep ambition and great accomplishment, Kuyper understood his primary vocation to be a follower of Christ. Yet he dabbled (and often excelled!) in an astounding number of spheres. Newspaper and university founder, pastor, theologian, journalist, politician, and eventually Dutch prime minister, husband, father, and more—Kuyper was larger than life, a giant personality who had keen and penetrating insights about the world but also could frustrate and even alienate those around him. During his lifetime the royal family of the Netherlands deemed him an “agitator,” and after his death, his thought became controversially associated with the apartheid movement in South Africa.

“Nothing but a man”

As the son of a Reformed pastor, Kuyper knew Calvinism from birth. As a young man, he studied theology at Leiden University and earned a doctorate in 1863 at the age of 26. But his faith faltered during this time. In one letter during this season, Kuyper wrote that Jesus “is not God to me, for my religious sense teaches me to know but one God. To me [Jesus] is man and nothing but a man.” It was a time of strong religious discontent for him.

Then, while finishing his doctorate, Kuyper experienced a conversion back to Christ through his reading of The Heir of Redclyffe (1853) by British novelist Charlotte Yonge. Forced to grapple with his own pride and self-limitations, Kuyper turned back toward the truth of the gospel and began going to church once again.

Upon graduation in 1863, Kuyper began serving as pastor at a small church at Beesd in the Dutch countryside. He also married Johanna “Jo” Hendrika Schaay (1842–1899); eventually, they would have eight children. At Beesd the Kuypers met a young woman named Pietje Baltus (1830–1914), an adamant defender of Calvinism. Baltus became key to Abraham Kuyper’s second conversion—back to the Calvinism of his youth. He is reported to have kept a picture of Baltus on his desk for the rest of his life.

As the tides of modernism churned around him, Kuyper came to believe Calvinism provided a firm grounding to both resist and engage the modern world—but he sensed a strong need to translate its truths for the challenges of his culture: new scientific discoveries, secular philosophies, industrialization and surging technological development, and politics. This mission continually fueled his academic, social, cultural, and political engagement.

Kuyper soon moved from Beesd in 1867 to pastor in Utrecht and then, in 1870, Amsterdam. Both cities were larger and more cosmopolitan than Beesd, and he became more active in the social and political questions of his day, gaining national attention. He founded a newspaper, continued his scholarly pursuits, and even organized a new Christian political party, the Anti-Revolutionary Party.

In 1873 he resigned from pastoral ministry to focus on journalism, politics, and academics, continuing his work on two Christian newspapers, founding the Free University and teaching theology there, publishing prolifically, and holding political office. In addition to various terms in the Dutch parliament throughout the rest of his life, he served as prime minister from 1901 to 1905.

While no longer a pastor, Kuyper continued to be active in the church. In 1886, troubled by growing liberal trends within the national Dutch Reformed Church, Kuyper led a church separatist movement, the Doleantie (“grieving ones”), to form a new Reformed denomination. In 1892 this movement joined with another separatist group also committed to orthodox Calvinism to form the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands. In 1899 Kuyper lost his beloved Johanna; she died in a Swiss hotel, where she fell ill while they were vacationing, and is buried in the Swiss Alps under a tombstone that reads, “Justified by faith, she had peace with God.”

Kuyper’s robust commitment to Calvinism—where, he claimed, his “heart has found rest”—animated his mature civic thought and action. Despite the piercing and sometimes polemical ways Kuyper expressed his convictions, his core conviction was that the good news of the gospel reaches far and wide, encompassing Christ’s redemption of and rule over the fullness of human experience and the whole of creation—a universality he believed best expressed in Calvinism.

Calvinism, however, has many caricatures. Kuyper battled several of them in his day, including at least one that persists into our own: that Calvinism is synonymous with the five points of the Canons of Dort (1618–1619), known popularly as TULIP. Kuyper argued that these convictions flowed out of God’s sovereignty “over the cosmos, in all its spheres and kingdoms, visible and invisible.”

Calvinism doesn’t start with salvation, argued Kuyper: it starts with creation! From this starting place came three of the major theological themes that undergirded much of his Christian civic engagement: creation’s multiformity, God’s common grace to all people, and sphere sovereignty.

From Genesis to Revelation

Kuyper argued that Christ’s work is one of restoration, bringing to fulfillment that which was intended from the beginning—thus we must pay close attention to how this world was originally created to understand how God intends it to be. For Kuyper one of the key components of God’s creation was that it is bursting with diversity, which he called multiformity.

In his 1869 speech “Uniformity: The Curse of Modern Life,” he looked to Genesis 1:11, where vegetation multiplied “according to their various kinds.” This verse has important implications for all of creation, Kuyper argued; it contains an “infinite diversity, an inexhaustible profusion of variations . . . in every domain of nature, in the ever-varying shape of a snowflake as well as in the endlessly differentiated form of flower and leaf.”

While our sinfulness drives us toward a kind of false unity, God’s kingdom is one of diversity. Scripture testifies to this multiformity, he argued, from Genesis to Revelation, where before the throne of the Lamb, doxologies will be sung to him who conquered not by a uniform mass of people but by a humanity diversified in peoples and tribes, in nations and tongues (Revelation 7:9–17).

Our role in this bustling, diverse creation isn’t static, argued Kuyper. Upon creating humanity in his image, God gave us the task to “fill the earth” (Genesis 1:28), a task he called the cultural mandate; humanity was tasked to steward and cultivate the “multiform world God had created, according to its kind”: technology, politics, art, language, cuisine, sports, and so much more.

However, Kuyper did not believe all diversity is good diversity. Sin’s corrupting power extends to diversity too. Kuyper paired his insistence upon God’s good, multiform creation with an equally strong insistence that creation was corrupted through human sin. Following Augustine and Calvin, Kuyper argued that our act of disobedience has wide-reaching implications that extend to the whole of creation.

Nevertheless Kuyper continued to assert that God’s will and plan for creation endures. In light of human sin, God extends a common grace to all of creation that continues to uphold the structures of creation: holding back the full effects of sin, providing natural blessings, and instilling the capacity for some virtue, love, creativity, and truth in all people. Thus our cultivating cultural task endures.

This common grace was not for Kuyper saving grace, “atonement for sin and salvation of souls.” That, said Kuyper, is exclusively for those who are in Christ. But all of humanity, and all of creation, are nevertheless recipients of God’s generosity.

Common grace undergirded Kuyper’s insistence that believers can share common ground, and even some common cultural cause, with nonbelievers; even those who are not in Christ, he wrote, can “amaze us with the many beautiful and true things [they] offer us.” Their good works and cultural development in science, politics, and art are a work of God in his creation.

God of gravity

In Kuyper’s Lectures on Calvinism, he famously declared that Christ’s rule and reign extend to every nook and cranny—every “square inch” of creation. From human endeavors to astronomical orbits, all are directed and designed by God and ought to submit to God. Natural laws necessarily submit to God’s design, even after the Fall, because of God’s common grace; liquids, for example, continue to turn to gas at a predictable temperature. For Kuyper, though, because God reigns over all, his pattern and norms extend to every part of life, including societal life. What is different with social norms, however, is that they can be disobeyed, and often are.

Kuyper used the language of “spheres” to designate the various institutions of society: education, church, state, family, business, art, and more. While he never gave an exact list of spheres, his writings give a general sense that these are distinct (but not disconnected) multiform areas of cultural and social interaction: “The cogwheels of all these spheres engage each other, and precisely through that interaction emerges the rich, multifaceted multiformity of human life.”

In their distinctions, however, each sphere has its own identity, authority, and norms. The church is not the state, nor does it govern itself in the same way. The family is not a business, nor are its relationships structured like a corporate office.

For Kuyper the designs and norms of family, church, and the rest are not arbitrary, nor human-made. They were designed by God and written into his creation, and he believed we violate them at our peril.

Sometimes Kuyper’s vision of Christ’s lordship over all the spheres has fed an overly transformationalist zeal among his followers. Some emphasize humanity’s task to bring about change without recognizing the priority Kuyper placed on God’s sovereignty–and the primacy of the actions of the Holy Spirit in us and in the world as we remain “near unto God” in piety, prayer, and worship.

Kuyper believed that only God’s action can awaken human hearts to hear the good news of Christ’s reign and send them out to engage the various spheres of life in faithful service to Christ. We are like strings that cannot make music without the initiative of the harpist; we stand, he wrote, with “strings tuned ready in the window of God’s Holy Zion, awaiting the breath of the Spirit.”

We offer our full selves to worship God, Kuyper said, in prayer and piety—but also as we create art, fine-tune scientific experiments, make business deals, run our households, make public policy, and go about all the other affairs of our daily lives.

The kingdom matters

Kuyper’s thought and work do contain some difficult and troubling aspects, particularly his association with apartheid South Africa. While sometimes the causal effect between the two is retold too starkly, Kuyper’s thought influenced apartheid’s development in at least two ways: he explicitly perpetuated the racial superiority of European ancestry over African ancestry, and his notion of clear separation between various spheres of society was used to justify racial segregation.

But his complex legacy also had positive effects. Many Christian universities have drawn on him to pursue integrated Christian thinking and learning for every discipline. Kuyper also lives on in institutions like the Christian Farmers Federation and the Christian Labour Association of Canada, which take seriously the claim that the gospel matters for every area of life, including raising livestock and negotiating labor relations.

In many ways Kuyper’s time was not unlike our own: rapid social change, massive upheaval, and religious crises. Kuyper sought to grapple with the cultural and religious changes of his day and find the concrete ways the gospel spoke amid those changes and to them. He called Christians to action in every sphere of creation and can still function as a signpost for us today.

As a later thinker in the line of Kuyper, Gordon Spykman (1926–1993), said: “Nothing matters but the kingdom, but because of the kingdom everything matters.” CH

By Jessica Joustra

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #141 in 2021]

Jessica Joustra is assistant professor of religion and theology at Redeemer University and associate researcher at the Neo-Calvinist Research Institute of the Theologische Universiteit Kampen. She is co-editor of Calvinism for a Secular Age: A Twenty-First-Century Reading of Abraham Kuyper’s Stone Lectures.Next articles

The national spirit

Two men whose civic engagement connected Christianity to korean independence

In Soo KimRepresentative of the outcast

Josephine Butler’s civic engagement helped improve the lives of Victorian women

Jane RobinsonBrave medical and theological sister

As doctor, activist, and ultimately theologian, Katharine Bushnell sought to improve women’s lives

Kristin Kobes Du Mez