Marching to Zion

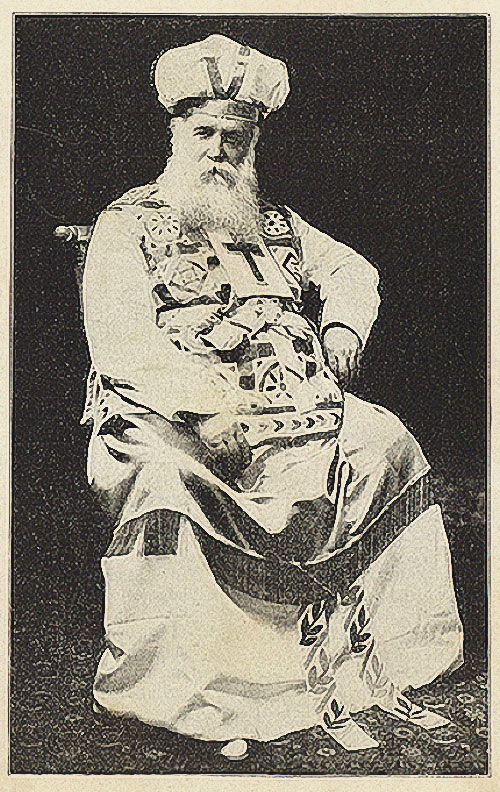

[Above: John Alexander Dowie, Leaves of Healing, 1904. Zion City, Illinois—Public domain]

Looking up the rickety stairs of the run-down building on Pitt Street in Melbourne, Australia, in 1886, Mrs. Spinks was deeply afraid. She had been suffering near-uncontrollable vaginal bleeding for months, accompanied by painful stomach cramps. She had consulted physicians—including the notorious Dr. James Beaney, who Melbourne society whispered had murdered a barmaid by operating upon her blind drunk—but none of these eminent male doctors had been able to help her.

They had only prodded her painfully with terrifying metal implements and recommended grisly sounding surgeries. She was left penniless and hopeless. Then she unexpectedly received a recommendation from her neighbor in the cramped building where she lived in Collingwood, one of Melbourne’s new urban slums. Her neighbor swore by the marvelous new faith-healing doctor all of Collingwood was seeing.

Dr. Alexander Dowie, a charismatic Scot, had left the Presbyterian Church to found his own Free Christian Tabernacle. Any Sunday, and several weekday evenings, shabbily dressed invalids could be seen pouring into the tabernacle on Pitt Street to undergo the electrifying experience of Alexander Dowie or his wife, Jane, laying hands on them and praying for their bodily healing in the name of “Zion”—the coming kingdom of God.

Physical Christianity

Melbourne—only declared a city in 1847—had seen new slums sprout up almost overnight, overcrowded and with terrible sanitation. Disease and bodily suffering abounded; churches and philanthropic associations were vocal in sanctimonious poor-shaming, recommending abstention from drink and saloons, better hygiene, and, above all, increased church attendance. Dowie, however, offered Melbourne’s working classes a different solution. Instead of moralizing and shaking fingers, his new church offered the promise of bodily healing to a community of broken-down and dispirited women and men.

Like the rambunctious Salvation Army and its belittled street processions, Zion was part of a broader interest in divine healing among late nineteenth-century Protestants who aimed at saving body as well as soul. Many advised true believers to steer clear of doctors and medicine and to rely on the therapeutic powers of faithful prayer.

Where more conventional evangelical churches bemoaned the urban poor as intemperate and morally dissolute, Dowie taught them that full salvation—body and soul—was just within their grasp if they only trusted in God. They did not need to spend hard-earned money on expensive physicians whose cures were largely ineffectual before the wide acceptance of germ theory.

In 1888 Alexander, Jane, and their two children set sail from Melbourne for San Francisco. Like other Protestant healers, Dowie was inspired by missionary zeal. After all, what could convince the unconverted as powerfully as a healing miracle? After a brief sojourn in San Francisco where hostile established churches drove them away, the Dowies settled in Chicago in 1892, drawn by the impending huge world’s fair along with hundreds of Protestant clergy who flocked to the city in search of souls.

Dowie decided the occasion offered an unmissable opportunity for divine healing to take root in the Midwest and North America. Unable to afford an actual fair site, he established the Zion Tabernacle in a rickety wooden structure on the fair’s perimeter, opposite Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. There he healed Buffalo Bill’s niece, Sadie Cody; her positive publicity in the Chicago Tribune attracted thousands.

Riding this wave of success, Dowie’s newly named Christian Catholic Apostolic Church in Zion became spectacularly popular among Chicago’s working classes. By the 1890s Chicago was second only to New York City as a labor migration hub. Extensive European immigrant populations and a sizable African American community made it one of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities.

This diverse population offered Dowie a chance to forge an aspect of his message absent in Melbourne: not only did faith healing promise to uplift the urban poor, it also offered a way for largely disenfranchised immigrants to see themselves as a new cosmopolitan breed of humanity.

Working-class Zionists—renouncing doctors and drugs in favor of prayer—would be marked by Christian piety, healthy bodies, and temperate lifestyles. They would also rise above differences of language, ethnicity, and race. This was the new human body as envisioned by the Creator: healthy, sturdy, and multiracial.

By 1900 Dowie had raised funds to buy property 40 miles north of Chicago on the shores of Lake Michigan. There he started a utopian experiment in holy living dubbed “Zion City”: drugs, doctors, alcohol, and tobacco were all banned. Zion City was proclaimed as a “home for all nations,” and over 70 nationalities lived there, including numerous African Americans with senior church positions. Dowie ultimately aimed to start a string of faith-healing Zion Cities throughout the world, sending missionaries to China, Japan, Mexico, India, Australia, New Zealand, and the South African Transvaal territory. There, in the 15-year-old gold mining metropolis of Johannesburg, Zion Church succeeded.

Another urban hub

Johannesburg resembled Melbourne and Chicago. Silicosis from inhaling dust particles from the mines and devastating injuries due to rockfalls and other mishaps were common. The city was also a cosmopolitan labor hub, drawing workers from Cornwall to California to Australia to southern Africa, including Portuguese East Africa (today Mozambique) and Nyasaland (Malawi).

The new Zion Tabernacle in downtown Johannesburg became notorious for its racially mixed faith-healing services. In the wake of the South African War (1899–1902)—a devastating conflict between Boer and Briton for control of Johannesburg’s gold—Dowie’s cosmopolitan message of reconciliation between races had particular resonance. Zion’s healing services often hosted tearful statements of reconciliation between these two formerly warring White “races.”

But Zion’s greatest popularity lay with Johannesburg’s Black South Africans. The church’s promise to transcend race and ethnicity appealed to Black citizens faced with political disenfranchisement and dispossession by White colonial authorities. Over the decades Johannesburg’s place as a magnet for African laborers from across southern Africa helped transform Zionism into a church with continent-wide reach and millions of members. Today an estimated 15 million southern Africans belong to a Zionist church.

In Johannesburg another young working-class woman was drawn to Zion in the early 1900s, also suffering from what she delicately called “female trouble.” Meta Budulwako was a young South African woman in domestic service to a White employer, part of the small class of educated Christian Africans disenfranchised by racist legislation. She was astounded when her White employer—a Zionist—laid hands on her and fervently prayed for her healing, a move that exemplified the countercultural, multiracial ethos of Dowie’s church. Budulwako’s family vigorously opposed her conversion, but so impressed was she by Zion—and especially its friendship between the races—that she persisted.

For two Zion women—Spinks and Budulwako—from two nineteenth-century imperial cities—Melbourne and Johannesburg, the promise of Zion was the same: uplift, dignity, and meaning amid social marginalization and rapid industrialization. In trauma, these women sought hope in the healing hands of Christ. CH

Testimony of Mrs. Bose Spinks

Collingwood, Melbourne

‘‘For 6 months I suffered from an internal tumour, which gave me much pain and bleeding, and grew at last to a great size. Doctors Danne and Singleton said it was no use me thinking of getting better without an operation. One Saturday night I made up my mind to seek the Lord for Healing. On Sunday, October 17, 1886, I was crying in the Tabernacle at an after-meeting with pain, Mr Dowie heard me and I told him about the tumour, which was so large in front of me I was ashamed. Then he called Mrs Dowie and asked her to take me into his room and pray with him. Mrs Dowie prayed and the pain went away, IN THREE DAYS EVERY PARTICLE OF THE TUMOUR WAS GONE ALTOGETHER. I am perfectly well tonight.’’

—Record of the Fifth Annual Commemoration of the Rev. John Alexander Dowie and Mrs Dowie’s Ministry of Healing Through Faith in Jesus (1888), p. 31

Testimony of Miss Meta Budulwako

Wakkerstroom, Transvaal, South Africa

‘‘My parents were heathen and knew nothing of the Word of God. In 1900, I went to work in Wakkerstroom and attended Zion meetings because there was no other place where religious services were held. Being strongly prejudiced, it was a hard struggle [for me] to accept the truth and submit to it. Shortly after this I became very ill. My stomach could not bear any food. Even a mouthful of water caused severe pain and swelling. I also suffered from female trouble. My heart was in rebellion against the teaching [of divine healing] but as I saw death was near, I consented to having healing prayer offered for me.

Rev. Pieter le Roux visited me several times and explained the Word and prayed for me by laying hands on me. As soon as possible, I made a full confession of my sin to him. I did as he advised me and God answered prayer for me. Today it is my privilege and joy to testify to being saved and perfectly healed. I am strong and happy, and thank God for Zion. To Him be all the glory!’’

—Leaves of Healing, October 8, 1904, p. 863

By Joel Cabrita

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #142 in 2022]

Joel Cabrita is assistant professor of history and director of the Center for African Studies at Stanford University and author of several books including The People’s Zion: South Africa, the United States and a Transatlantic Faith Healing Movement.Next articles

Christian History Timeline: The gospel brings healing

Church history is brimming with stories of divine healing; here is a timeline of some featured in this issue

the editorsPower in the blood

Divine healing at the Azusa Street revival and in early Pentecostalism

Gastón EspinosaExtraordinary becoming ordinary

Charismatic renewal and healing prayer in mainline denominations

Amy Collier ArtmanHealing power

How a pastor and a professor prayed for healing and started the third wave movement

Caleb Maskell