People who steal the soul

When Martin Luther accepted safe conduct from Emperor Charles V to defend his writings before the Imperial Diet at Worms, he knew full well that events might take a lethal turn. After Luther’s excommunication the previous year, the deck was stacked against him; the papal ambassador heading up the opposition to Luther at the diet was already fulminating against the “heretic who brought up Jan Hus from hell.”

This was an ominous comparison. Hus had also been granted a safe conduct to the Council of Konstanz a century earlier by Sigismund of Hungary, but Sigismund’s bishops soon convinced him that an oath made to a heretic was not binding, and he burned the Bohemian reformer rather than honor the safe conduct.

Whether or not Luther ever actually uttered “Here I stand” at the Reichstag in 1521, the spectacle of an embattled theologian refusing to back down before the assembled princes and prelates of the Holy Roman Empire is rightly seen as one of the most compelling events in Christian history. But why were those princes and prelates calling him to account? Why were they willing to kill for the sake of religious uniformity? And why was heresy a capital offense?

A stubborn error of the will

According to St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) in his Summa Theologiae, heresy was “a species of infidelity in men who, having professed the faith of Christ, corrupt its dogmas.” Each part of this definition requires explanation. First, heresy was not merely ignorance or confusion—not simply an error of the intellect, but of the will. A heretic was someone who stubbornly and pertinaciously clung to error, even after having received pastoral correction.

Second, heresy was by definition an in-house dispute among baptized Christians; Jews, Muslims, and other non-Christians were not subject to Christian spiritual jurisdiction. As one expert in canon law remarked, “[Jews] are not members of the Christian church, and their faith is not our business.”

Third, heresy involved the public subversion of the church’s settled teachings. Doubts or misgivings one might hold in the quiet of one’s mind might well jeopardize one’s personal salvation, but God alone was the judge in such matters. The wheels of church discipline only turned when such doubts, misgivings, or outright contradictions were publicly advanced in defiance of the church’s authority.

Order Christian History #118: The People’s Reformation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Church and state saw a heretic, in effect, as a person who elevated his or her own private judgment above that of the one institution that God had appointed by God for transmitting and preserving the only truth that could save humanity from eternal damnation. This helps to explain why heresy was so terrifying.

Unlike a common thief stealing temporal goods of finite value, a heretic could steal eternal goods of infinite value, as Catholic writer Antoine Du Val (1520–1600) wrote: “If it is right that thieves, murderers, and robbers are punished, is it not with greater reason that one ought to punish heretics, who steal the soul and the understanding from those they deceive?”

Moreover the church felt that heresy was like a disease, liable to spread if left unchecked. Innocent III (1161–1216), the medieval pope who perhaps did more than anyone else to establish the church’s role in rooting it out, argued that heresy was “like a cancer . . . creeping imperceptibly wider in secret.”

Nor was this view limited to popes or inquisitors. Writing in defense of Geneva’s decision to execute anti-Trinitarian heretic Michael Servetus in 1553, John Calvin argued that it was necessary to punish heretics because “they infect souls with the poison of depraved dogma.” It was far kinder, he felt, to excise the diseased member than to let the patient (Christendom) die from the contagion.

Sympathy with the heretic

Capital punishment was usually viewed as the remedy of last resort, when all other means of reclaiming the wayward soul had been exhausted. Church authorities recognized that a repentant heretic who confessed his or her errors was a far more powerful testimony to the true faith than a defiant one who might inspire sympathy.

Also, the task of trying and convicting heretics often fell on the shoulders of local magistrates who felt unqualified for the job or were even sympathetic to their accused neighbors. The case of one early Anabaptist martyr, Augustine Würzelburger, from a small southern German village, illustrates this. After word of an Anabaptist group prompted an investigation, city magistrates questioned Würzelburger. Respectful, though undaunted, he confessed that he had indeed rebaptized a number of his friends and family members, urging them to avoid attending Mass and rest their faith on the Scriptures alone.

The City Council had no choice but to report this to the dukes of Bavaria, who promptly ordered burning at the stake. The council’s reply, in a letter dated June 5, 1528, is a poignant indication of just how little the city fathers relished their task:

We are grieved indeed by Würzelburger’s error, since he has no other fault than this concerning rebaptism and the faith. We cannot understand why we are to sentence him to death. We wanted to make him desist from his opinion and error.. . .

The dukes’ reply has not survived, but its content can be inferred from the fact that Würzelburger was executed on October 10. The council’s minutes record that it “had mercifully ruled that he was to be executed by beheading.”

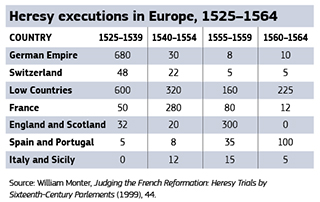

From the early 1520s to the 1650s, around 5,000 men and women were executed for heresy or religious treason. This figure, of course, excludes many deaths resulting from nonjudicial murder, mob violence, and religious warfare. Approximately 4,100 Protestants and Anabaptists were executed for heresy in Europe between 1523 and 1574; an additional 280 executions followed between 1575 and 1600. Five hundred Catholics were executed for treason in England between 1535 and 1680, and 140 priests in the Low Countries between 1567 and 1574.

It is important to see these statistics in the wider context of an early-modern criminal justice system heavily dependent on capital punishment. In the sixteenth century, there were scores of capital crimes: treason, murder, theft, counterfeiting, witchcraft, and sexual crimes (rape, incest, bigamy, sodomy, sex with a nun, etc.). Between 600 and 1,200 people were executed every year in England throughout the Tudor era, and only a tiny fraction of these cases involved charges of heresy.

Catholic authorities, primarily in France and the Low Countries, carried out around 90 percent of the executions for heresy in this period. This probably represents a disparity in opportunity rather than in willingness to kill: because Catholicism was established, Catholic countries already had judicial infrastructure in place to detect, try, and convict. By the time Protestantism had become established in Europe, the notion that executing heretics could protect a unified religious culture was considerably weaker.

Don’t challenge the king

In the Holy Roman Empire, Protestantism secured its position through the principle that the ruler of the territory determined its religion. What this meant in practice was toleration for competing versions of Christian faith. Princes and city councils wished to maintain religious orthodoxy within their domains, but when neighboring cities or territories gave their allegiances to opposing beliefs, it became impractical to prosecute every instance of theological deviance. It was often far less trouble to encourage religious dissidents to emigrate, or to work out a grudging toleration.

In other parts of Western Europe, however, toleration emerged more slowly. In England and France, concentration of political power in the hands of the monarch meant challenges to the established religion were viewed as challenges to the authority of the king. Beginning with evangelical humanist Louis de Berquin, burned at the stake in April 1529, the Parlement of Paris continued executing suspected Protestants at an accelerating pace until France became engulfed in religious warfare beginning in 1562. Only with the Edict of Nantes in 1598 did French Protestants—Huguenots—finally gain legal recognition. Even this was not permanent. Louis XIV revoked the edict 87 years later, sending a wave of Protestant artisans, scholars, and merchants into exile throughout Western Europe.

In England all the Tudor monarchs showed themselves quite willing to inflict ghastly penalties on dissidents. Beginning in 1401 the crown took a hard line against home-grown heresy, executing several hundred “Lollards” in the years leading up to the Reformation. Henry VIII was granted the title of “Defender of the Faith” in 1521, in part for his writings against Luther.

Yet when the pope proved uncooperative in solving Henry’s marital difficulties, the king nationalized the English church in 1534, leaving those who had formerly defended the old religious order in a precarious position. No one felt the sting of the rapidly changing political landscape as dramatically as Henry’s trusted adviser and confidant, Sir Thomas More, lord chancellor and a vigorous prosecutor of heresy.

Burning more in seven score

More expressed his fears in 1532 that the government was not adequately suppressing Protestant views seeping in from the Continent: “There should have been more burned by a great many than there have been within this seven year last passed; the lack whereof I fear me will make more burned within this seven year next coming than else should have needed to have been burned in seven score.” Three years later, however, More’s allegiance to papal supremacy cost him his life.

After More’s death Henry’s government continued its campaign, burning about half a dozen English “Lutherans” and 20 Dutch Anabaptists over the course of the next decade. Following Henry’s declaration of royal supremacy, over 200 Catholic loyalists were executed for opposing the king’s dignity. In Protestant England heresy had been redefined as treason.

Only two heretics (an English Anabaptist and a Dutch Arian) were burned during the reign of Edward VI, though the government mandated church reforms designed to move the country in a decisively Protestant direction. This was dramatically reversed when the sickly Edward died in 1553 and his militantly Catholic sister became Queen Mary I. The traditional view, originating in the wildly successful martyr accounts of John Foxe, was that Mary was a reactionary fanatic, bent on imposing her faith upon an unwilling populace by dint of brute force. Her bloodthirsty slaughter of 300 Protestants in six years was viewed as barbaric, even by the standards of the day.

Few today would defend Mary’s policies on their own terms, but historians have recently argued that Mary’s campaign to suppress Protestantism had wider popular support than believed and was largely effective in stemming the spread of Protestantism in England—it might well have returned England to the Catholic fold, had Mary lived to see her plans through. Moreover the contrast between “Bloody Mary” and “Good Queen Bess” may be overdrawn. Eamon Duffy pointed out that “Elizabeth I burned no Catholics, but she strangled, disemboweled and dismembered more than 200” in her 45-year reign. Unlike her half-sister, Elizabeth had no John Foxe to publish her brutality to a horrified domestic readership.

As the sixteenth century wore on, prosecutions for heresy continued to dwindle. But as national churches with authority tightly intertwined with that of the state replaced the authority of a single, transnational church, treason replaced heresy. And the results were often no less bloody. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #118 The People’s Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By David C. Fink

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #118 in 2016]

David C. Fink is assistant professor of the history of Christianity and Christian theology at Furman University.Next articles

The accidental revolution

The English Reformation began with a king but took hold among a people

Melinda S. ZookA motley, fiery crew

Sometimes difficult, always committed, these men advanced the Reformation in Germany, Switzerland, and England

David C. Steinmetz and Edwin Woodruff TaitThe people's Reformation: Recommended resources

Where can you go to learn more about the “people’s Reformation”? Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors.

the editors