Serving the true Lord and God

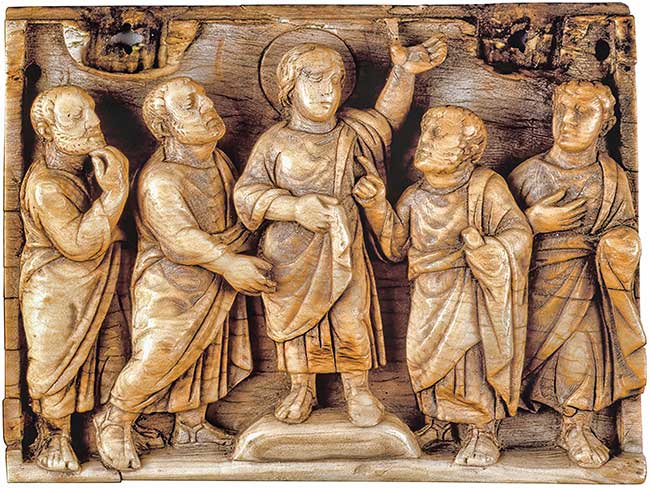

[Casket with Resurrection, c. 420 to 430. Roman—[CC BY-NC-SA 4.0] © The Trustees of the British Museum]

The Roman world was a bloody world. Unforgiving. After two centuries of expansionism and civil strife, the celebrated Pax Romana (Peace of Rome) was achieved at the point of the gladius (sword) and was protected by Rome’s 28 legions and the gods who superintended it. By the time of Constantine in the fourth century, massive military apparatuses greatly surpassed the ideals of the early empire and expanded to over half a million troops and almost an equal number of auxiliaries.

Rome’s first emperor had ascended to power at the conclusion of the civil wars of the 40s BC. Throughout his reign Octavius, who embraced the title of Augustus, carefully kept the appearance of coveted republican ideals of virtue and simplicity. He knew full well that the future of the empire rested on the emperor’s ability to maintain the delicate balance between the decreasing influence of the Senate and the ever-increasing might of the Roman military he alone commanded.

The family of his adoptive father, Julius Caesar, claimed descent from the goddess Venus, and many thought Caesar himself had ascended to the heavens upon his assassination in 44 BC. Though Augustus declined to be worshiped as a god during his lifetime, he claimed the title of “son of the divine one” and used it often in his imperial iconography.

The Romans turned to Augustus to restore the customs and ideals of their ancestors, believed to have been jeopardized during years of civil strife. In 9 BC, the Senate consecrated the Altar of Augustan Peace, and the people of Rome celebrated the peace Augustus had restored, considered to be the “Peace of the Gods.” During his rule Rome became the greatest empire the world had ever seen.

Behavior, not belief

Even though ancient Romans had a keen sense of sacred space and sacrifice and built massive temples to the gods, Roman religion was not concerned with distinguishing true from false beliefs: proper behavior characterized the life of the Roman citizen. The ubiquity of local shrines and temples, festivals and sacrifices, votive offerings and oracles intertwined the sacred and the secular, the political and the religious.

During the period of Christianity’s early existence, the imperial cult became an overarching symbol of everything connected with Roman religion, including the very notion of the state. The people performed sacrifices on behalf of the emperor, not necessarily offering them to him. They focused on the person of the emperor as the vicar of the gods on earth and as the people’s representative to the gods—called at various times “Revered, Savior, Liberator,” “Father of the State,” “High Priest,” and “Diviner.” But by the end of the first century, Emperor Domitian (81–96) was called not simply “son of the divine one,” but took on the title of a Dominus et deus (Lord and god). And by the time of Diocletian (284–305), this transformed into the absolute rule of a dominus, a god on earth.

Romans saw the worship of the gods and the sacrifices offered to them as essential for all aspects of life. The secrets of the future could be read in the entrails of slaughtered animals. Romans sealed contracts, decrees, and laws with sacrifice. Marriages would be blessed, and households would become prosperous.

Proper sacrificial libations averted disease and illness and rendered the daily meal safe; a welcomed gift from the gods to whom the libation was offered. Armies never marched without a favorable divine omen and a reading of animal entrails. For the most part, Greeks and Romans understood three reasons for sacrificing to the gods: (1) to honor them, (2) to express gratitude to them, and (3) to obtain some benefit.

A foreign cult

Historians find the first mention of the Christian movement by a Roman writer in the correspondence of Pliny the Younger (c. 61–113; see p. 33). Appointed governor of the province of Bithynia, he asked advice from the emperor Trajan on various matters, including how to engage this new group of whom he had never heard before. Pliny identified Christianity as a superstitio, a cult—and a foreign one at that.

For almost a century, small Christian communities arose primarily within a few urban centers around the Mediterranean basin and went unnoticed by most of the empire. But the inevitable clash occurred as a result of Christianity’s expansion—and its ideological collision with the claims of Rome. Christians confessed Jesus, not Domitian or any other emperor, as Dominus et deus—a public declaration with grave temporal as well as eternal implications.

Until almost the middle of the third century, Romans saw Christians primarily as a schismatic Jewish sect, a corrupt off-shoot without the historical protections extended to the Jews. Christianity’s claims to exclusivity, its rituals of initiation and worship, the borderless character of its community, and its professed disregard for distinctions based on any of the markers that guided Roman social relationships, raised Roman suspicion—and often ire.

When public sacrifices were ordered for the welfare of the emperors or collectively offered to the gods on behalf of the state, the Christian refusal to obey the law, honor the gods, and submit to the orders of the emperors was an act of civic and religious blasphemy.

For the most part, Romans were not in the business of making martyrs. They preferred that accused people recant and profess loyalty to the emperor and the gods. Persecutions directed specifically against Christians as an identifiable group were sporadic and local before the sustained empire-wide persecutions of the mid-third century under Decius (249–251).

Yet even from the earliest years, Christians felt the power and whims of the mob in multiple and various local instances (Acts 14, 16, 19) and suffered persecutions at the hands of Nero, Domitian, and Trajan. Women and men were brought before Roman magistrates like Pliny to “give an account for the hope that was in them” (1 Pet. 3:15). Accounts of these collisions were called a martyrium (report of the martyr’s death) a passio (passion narrative), or an acta (acts of the martyrs). Martyrologies, as these texts are known collectively, were very popular among the faithful, and some survive today.

Christians inherited their notions of martyrdom from their Jewish heritage, especially the martyrdom accounts of the Maccabees, who defied Antiochus IV and Seleucid domination and suffered death for their unyielding faithfulness to God. Their primary inspiration, however, came from the power and hope of the resurrected Jesus (1 Cor. 15:13–14), whose life and example they were called to emulate.

Jesus had warned them that, in response to his call to discipleship, they would be persecuted at the hands of the status quo (e.g., Matt. 10:16–42, John 15:18–35), and he had called his disciples to see themselves as “blessed” when reviled and persecuted on his account, assuring them of the kingdom of heaven (Matt. 5:10–12; Rev. 21:7).

Early Christians believed that martyrdom was a baptism in blood, a eucharist in which one drank the cup of sufferings of Christ (Matt. 20:22). Paul had spoken of the redemptive role of suffering for the faith in his letter to the church in Philippi (Phil. 3:10). The Holy Spirit filled these martyrs, giving them words to say to the authorities and to each other; visions of heaven; and supernatural strength to endure sufferings.

Instead of the sacrifice of incense and grain demanded by the state as signs of loyalty expected from those living under the protection of the Roman gods, the Christian martyrs offered an alternative sacrifice: themselves, in imitation of Christ.

Noble athletes

Toward the end of the second century, Christians felt quite keenly Marcus Aurelius’s (160–180) stoic disdain for religion. After a short-lived interim of peace during the reign of Commodus (180–192), Septimius Severus (193–211) carried out the harshest persecutions experienced by the church to that time. Tertullian wrote his treatise To the Martyrs during this brutal period. After 177, senatorial decrees consigned Christians to the arena to face gladiators in an attempt to reduce and regulate the costs of gladiatorial games throughout the empire.

Christian martyrs included young and old, educated and uneducated, women and men, slaves, free people, Romans, and foreigners, almost none of whom shared Rome’s classical heroic ideals. They challenged directly the authority of Rome to dictate their conscience.

Trials were theatrical performances, and the audience expected customary responses from the accused; they were expected to blush, to sweat, and to show signs of fear and shame—bowing, scraping, and weeping to proclaim their repentance and to ask for forgiveness. It was not so with the Christians. To magnificent and terrifying displays of state power, Christians in early martyr accounts responded with calm defiance and even joy.

Condemned to face the beasts and the gladiators in Carthage in the spring of 203, Vibia Perpetua, a woman of noble birth and a young mother; Felicity, her slave (who herself had just given birth); and their fellow Christians entered the arena as “noble athletes”:

The day of their triumph dawned, and they cheerfully came forth from the prison to the amphitheater, as if to Heaven, with their faces composed; if perchance they trembled, it was not from fear but with joy. Perpetua was following with a bright face and with calm gait . . . by the power of her gaze casting down everyone’s stares. Also Felicity came forth, rejoicing that she had safely borne her child, so that she could fight the beasts, going from blood to blood, from the midwife to the gladiator, about to wash after childbirth in a second baptism. . . . [Perpetua] howled as she was punctured between the bones and herself steered the erring hand of the novice gladiator to her own throat. Perhaps so great a woman, who was feared by the impure spirit, could not be killed in any other way than unless she herself wished it.

Martyrdom was not the fate of the powerless, finally forced to admit the grandeur of the state. Martyrdom was a witness to the state of its subordination to the God of heaven.

Citizens of heaven

This found full expression in the works of apologists of the second and third centuries who wrote especially during times of persecution. They made the point frequently that God appoints kings and dispenses kingdoms, and it is to this God that Christians owed their loyalty and this God in whose kingdom they held citizenship (John 18:36; Phil. 3:20). As for now, as it was said in the “Letter to Diognetus,” Christians “live in their own countries, but only as nonresidents; they participate in everything as citizens, and endure everything as foreigners. . . . They live on earth, but their citizenship is in heaven.”

Christians insisted they were taught to respect the authorities. They had never rebelled, the apologist Tertullian argued, they were not seditious, nor did they take revenge, or even resist. Christians, he and others claimed, injured no one, countered enmity with acts of kindness and charity, and offered the state a much greater benefit by praying to the true God for the emperor and the welfare of the empire. Hippolytus wrote:

This is always the devil’s way in persecuting, in afflicting, in oppressing Christians: to stop them from lifting blameless hands in prayer (1 Tim. 2:8) to God, knowing that the prayer of the saints obtains peace for the world, punishment for wrongdoers.

Christians insisted that their behavior ought to be interpreted as a call to the state to repent and acknowledge its proper place under the authority of God (John 19:11). It was civil disobedience. CH

By George Kalantzis

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #147 in 2023]

George Kalantzis is professor of theology and director of The Wheaton Center for Early Christian studies at Wheaton College. He is the author of Caesar and the Lamb, from which this is adapted with permission, and the author, editor, or coeditor of a number of other books on early Christianity.Next articles

“This superstition”

Pliny, Roman governor of Bithynia in the early second century, asks for advice on how to deal with the Christian movement

PlinyThe emperor and the desert

Christian commitment to asceticism grew in a newly legalized faith

Kate CooperQuestions for reflection: Everyday life in the early church

Reflect on life among the earliest followers of Christ

the editors