To make whole

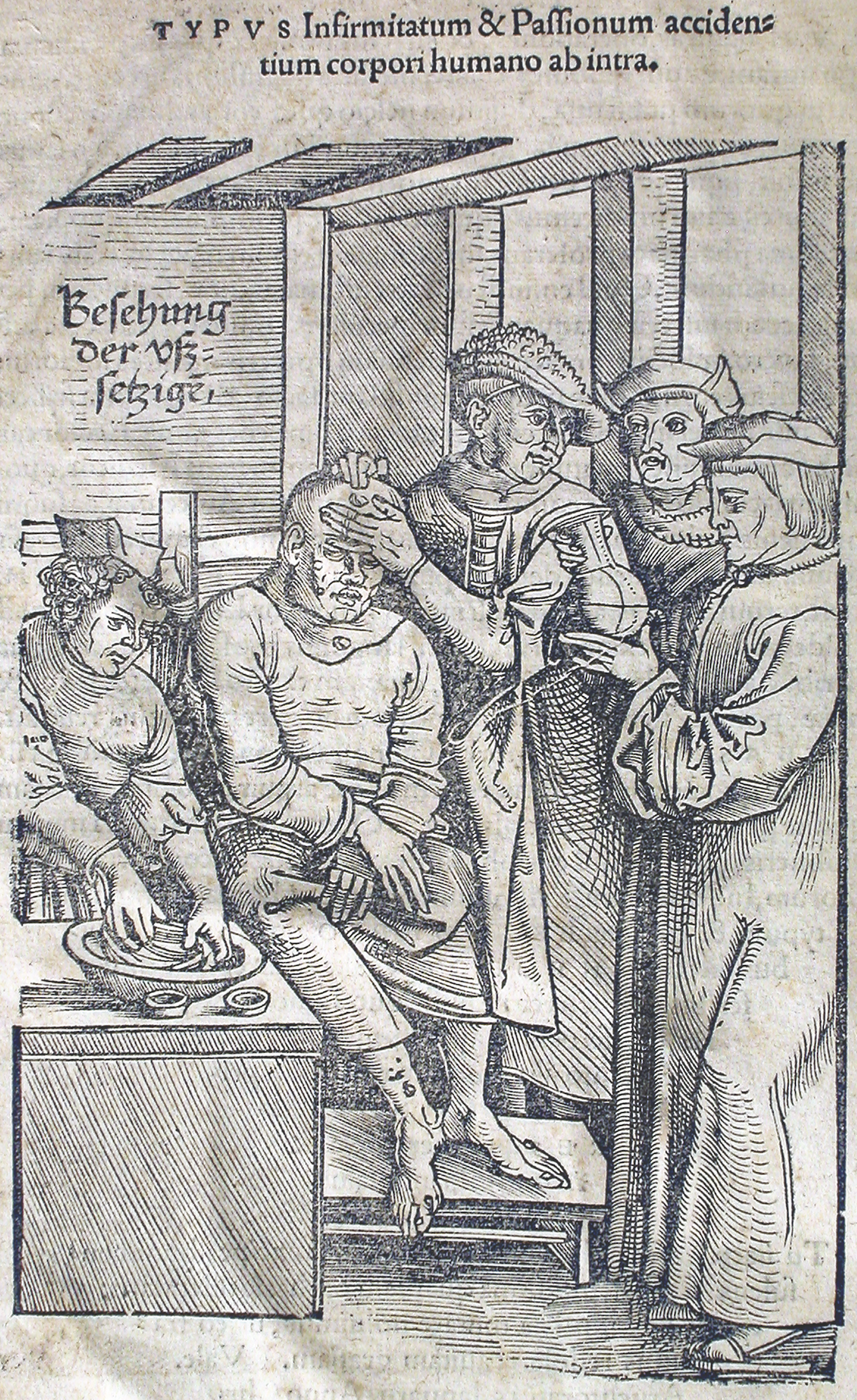

[Plate from Hildegard of Bingen, Physicas (Argentorati, 1533). Public Domain—Images courtesy History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries]

Oats (avena) are hot, with a sharp taste and strong vapor. Oats are a happy and healthy food for people who are well, furnishing them with a cheerful mind and a pure, clear intellect. . . . One who has a rash should . . . take the stem and leaves of lilies and pound them [and] knead this juice together with some flour, and keep anointing the part of the body which suffers from rash. . . . The odor of the first buds of lilies, and indeed the odor of the flowers, makes a person’s heart joyful and furnishes him with virtuous ideas.

Thus Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) described the medicinal value of oats and lilies, just two out of the nearly 300 herbs, plants, and trees detailed in her work Physica. She offered hundreds of natural cures, ranging from compresses for the eyes to potions for drinking. While many of these home remedies seem antiquated to the modern reader, others are remarkably relevant: they describe the value of aromatherapy and the connections between gut, mind, and mood that are at the cutting edge of research today. Over 800 years after her death, Hildegard was named a doctor (teacher) of the Catholic Church in 2012, only the fourth woman to receive this honor.

“The vault of heaven”

Born to a noble family, Hildegard was abbess of two Benedictine monasteries that she founded along the Rhine River in Germany. She was originally sent to the monastery of Disibodenberg as a child—perhaps as young as eight—and remained a nun for the rest of her life, eventually being elected by the other nuns to lead the community when she was in her late thirties. Through perseverance she won an independent location for her nuns about a decade later. Even as a child, her interests were broad and deep:

From my early childhood . . . I have always seen this vision in my soul, even to the present time when I am more than seventy years old. In this vision my soul, as God would have it, rises up high into the vault of heaven and into the changing sky and spreads itself out among different peoples, although they are far away from me in distant lands and places. . . . I am constantly fettered by sickness, and often in the grip of pain so intense that it threatens to kill me, but God has sustained me until now. The light which I see . . . is far, far brighter than a cloud which carries the sun. I can measure neither height, nor length, nor breadth in it; and I call it “the reflection of the living Light.” And as the sun, the moon, and the stars appear in water, so writings, sermons, virtues, and certain human actions take form for me and gleam.

Hildegard has been appreciated over the centuries for her morality play Ordo Virtutum (Order of the Virtues, c. 1151)—the first known morality play in history—as well as her writings on theology and spirituality. Beyond these specifically spiritual contributions, however, she was also a polymath—dabbling in everything. She painted beautiful illustrations for her books, composed music still played today, and became especially known for her work as a naturalist.

Fascinated with the world in which we live, she contributed to the study of the therapeutic value of animals, birds, fish, and minerals; served as an apothecary; and provided medical care to many who came to see her. Far from being a heavenly minded saint who was no earthly good, Hildegard ministered to the physical and spiritual health of untold numbers of people.

The whole person

Hildegard researched and prescribed herbal cures out of care for the whole person and concern for the well-being of others: body, soul, and spirit. As well as wanting people to draw close to God, Hildegard also desired them to be in good health: healthy and holy. Indeed, in both German and English, the words “health” and “holiness” come from the same root, meaning “to make whole.”

Hildegard looked at many aspects and ailments of the human person in her cures—from digestion to balding, from dreams to eyesight. She explored psychology and physiology, and even prescribed the appropriate age for marriage and procreation. Surprisingly for a nun, she discussed specific sexual issues (in discreet terminology): the pleasures of sexual activity, the dangers of sex outside of marriage, and nocturnal emissions. She offered remedies for menstrual difficulties in women and for diluted semen in men, so families would be able to have children.

In her Causes and Cures, Hildegard recognized the body-soul interrelatedness of human beings, addressing issues such as madness—proposing what she saw to be the physical dynamics of uncontrollable “rage” as well as the spiritual forces at work. She likely composed music at least in part because it helped to dispel “melancholia,” a generic term including various types of depression.

The unique and valuable observations in Hildegard’s writings on cures stemmed from her appreciation of balance in the human organism. Following medical thought prominent since antiquity, Hildegard saw the human body as containing four “humors”—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. But it was Hildegard who originally asserted that for us to be healthy, these humors need to remain in balance, just as medieval people thought the four elements of the universe should be. She stressed the need for bringing them back to equilibrium, much as modern medicine recognizes the need for hormonal and chemical balance in the body.

Likewise Hildegard sought equilibrium between the ancient Hippocratic “hot” and “cold,” as well as the “moist” and “dry” qualities of things. To treat body and spirit, one needed to know what combination of these attributes each herb contains: “Every plant is either hot or cold, and grows thus, since the heat of the herbs signifies the spirit, and the cold, the body. . . . If all herbs were hot and none cold, they would cause difficulty to the user. If all were cold, and none hot, they would provide an imbalance in people.”

Grand scheme of creation

Hildegard’s interests in the healing and sustaining powers latent in creation went far beyond herbs. Her Physica also catalogs scores of plants, elements, trees, stones, fish, birds, animals, reptiles, and metals—describing each and stating how it can be used for various ailments. Along with her descriptions of how nearly 230 plants should be cooked or boiled, she detailed 36 species of fish and other aquatic animals; 72 birds and insects; 45 land animals, informing her readers which are beneficial as food and which are not; and no less than 63 varieties of trees from around the globe, as well as various precious stones, presenting the putative healing value of each.

Causes and Cures, Hildegard’s larger work in medicine, offers a more comprehensive discussion of the natural world and human bodies. Hildegard explored the sources of various illnesses and addressed human sexuality, sleep, nutrition, bathing, and skin complexion; even including instruction on phlebotomy—bloodletting—a common medical practice that sought to detoxify the body, as well as more cures for the illnesses she had identified. She even addressed how the various phases of the moon affect us.

Not the first to make such a compendium of ailments and their cures, Hildegard clearly followed her predecessors. Because professional physicians were few and expensive, apothecaries performed much medical care up to the twelfth century; many were monks and nuns. (Read more about this in CH 101—Editors). Rather than being isolated from the world, medieval monasteries provided medical care to ailing and aging monks and nuns and also to local townspeople who regularly came for help.

Monastic houses cultivated herb gardens for medicines and maintained libraries with medical books. In fact most works on home cures were produced and copied in monastic scriptoria. Hildegard was well read, and her works summarize much of the thinking of the day. But she took the bold step of inserting her own insight and application throughout.

Hildegard placed her study of the natural world and herbal medicines in the grand scheme of God’s creation and plan of salvation. She believed that God created a good universe filled with heavenly harmony and teeming with the fiery power of God’s Spirit. She wrote of “the fiery life of divine essence . . . [which] awaken[s] everything to life.” All of creation is orderly and benevolent, she said, maintaining a balance of the classic four elements of the universe: fire, air, water, and earth. Such balance, she posited, would remain until Judgment Day.

Following the opening chapters of Genesis, she saw man and woman as the apex of creation: “With earth was the human being created. All elements served mankind and, sensing that man was alive, they busied themselves in aiding his life in every way. And man in turn occupied himself with them.”

That pristine state of creation did not last, however. At the serpent’s temptation, Adam and Eve rebelled against God. The Fall brought corruption not only into human souls but also into the physical world: “Driven into a wretched exile, they became corruptible along with the other fruits of the earth. At their fall and banishment all creatures of the earth were darkened.”

Even after the Fall, however, some of the goodness of nature remained; so she felt it was humanity’s task to learn which plants and animals are now healthy for us and which are not. Just as God provided a way for the human soul to be redeemed, God had offered much goodness in plants, food, and even minerals for the healing of our ailments. Hildegard’s concern came from her understanding of a Creator who heals and saves. Humankind is both part of creation and given the task to explore nature and use it.

Like the sun and moon

Hildegard saw humans as a microcosm corresponding to the macrocosm of the universe. Just as we need sleep to regain our strength, so in nature growing plants are restored during the fallow winter months. “As the soul holds the entire body of a human being, so the [four winds of the earth] hold together the entire firmament.” She added, “[our] eyes are made according to the likeness of the firmament. The pupil of the eye has a likeness to the sun, the black or grey color around the pupil has a likeness to the moon.”

Though she spoke to her own times, this cloistered noblewoman has lessons for ours: to embrace God’s good creation; to pursue knowledge and read broadly in the sciences; to care for the whole person, the physical body as well as the human spirit; to be attentive to balance and moderation; and to take a fresh look at alternative approaches to wellness. Perhaps above all Hildegard provides a model for viewing science, our lives, and all of nature in the grand scheme of God’s economy of creation and salvation: with each detail of the cosmos—from the furthest-flung galaxy to the smallest subatomic particle—part of a divine metanarrative being told by the God of love.

The more we grasp the grandeur of the Creator revealed in the beauty, awe, and detail of the universe, the more we see how science and faith belong hand in hand. Hildegard’s very heavenly mindedness enabled her to be of utmost earthly good, bringing healing to people all around her through wise understanding and careful use of God’s creation. CH

By Glenn Myers

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #134 in 2020]

Glenn E. Myers is professor of church history and theological studies at Crown College and the author of Seeking Spiritual Intimacy: Journeying Deeper with Medieval Women of Faith as well as articles on mysticism in the Dictionary of Christian Spirituality and elsewhere.Next articles

Understanding God through light and tides

Nicholas JacobsonChristian History Timeline: Faith and Science

A few of the highlights of Christian exploration of science that we touch on in this issue

the editors