Preachers and printers

Without printing, would there have been a Protestant Reformation? Only a century earlier, both John Wycliffe and John Hus spawned movements of intense spiritual fervor and wrote prolifically. But the absence of adequate printing technology limited the distribution of their works. Wycliffe was condemned, Hus burned at the stake, and history casts both as mere harbingers of the main event. John Foxe wrote of the change printing had wrought in his famed Book of Martyrs: “Although through might [the pope] stopped the mouth of John Huss, God hath appointed the Press to preach, whose voice the Pope is never able to stop with all the puissance of his triple crown.”

Johannes Gutenberg pioneered printing with movable type in Mainz, Germany, in the mid-fifteenth century. Within a few decades, the new technology spread throughout all of Europe; virtually all major cities in Italy, Germany, France, Spain, and England had presses. Suddenly there were many more books in the world, and each book took less time to produce.

Scholar Elizabeth Eisenstein wrote: “A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about 8,000,000 books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in A.D. 330.” A single working press might produce 3,600 pages a day, whereas a monk might have copied four or five.

It took early printers themselves several decades to come to terms with the press’s full potential for speed and new design; the earliest printed books imitated their manuscript counterparts. But by the time of the Reformation, printing was a fully developed business enterprise with established conventions. Luther, who would later use the printing press with great success, was initially surprised at its effectiveness; within two weeks of the posting of his 95 Theses, they were printed without his permission and distributed throughout Germany. Within a month they flooded Europe. Six months later Luther explained to Pope Leo X, “It is a mystery to me how my theses . . . spread to so many places. They were meant exclusively for our academic circle here.”

Between March 1517 and the summer of 1520, 30 of Luther’s pamphlets ran through a total of 370 editions: 400,000 of his pamphlets alone flooded Germany. From 1517 to 1523, publications in Germany increased sevenfold. Half of these writings were by Luther.

Work for the whole family

What did a sixteenth-century print shop, the seat of all this ferment, look like? A typical print run for a book ranged from 1,000 to 2,500. The operation of a printing press required typecasting, typesetting, inking, and pressing; the finished pages were hung up to dry before being folded and sometimes sewn together. The trade of the bookbinder was separate from the printer; all books were sold as “paperbacks” ready for binding at the purchaser’s discretion.

Printers’ families usually got in on the act, and printers employed workmen and apprentices who lived with the family, receiving room and board in exchange for their labor. Sixteenth-century Parisian printer Charlotte Guillard (d. 1557) managed a book shop and four or five other presses, paying and feeding 12–25 workers plus domestic staff and an accountant. Printing was termed a “free” enterprise in most cities with no requirement for membership in a guild (an association of craftsmen that controlled the practice of a certain craft in a given area). However, many printers still joined guilds.

Order Christian History #118: The People’s Reformation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Printers sold books directly from their print shops, via travel (booksellers crisscrossed Europe) or, not always successfully, at book fairs. (Zürich publisher Christoph Froschauer took 2,000 copies of one work to a book fair in Frankfurt in 1534 and came home having sold only half of them.) A small quarto pamphlet cost the equivalent of a chicken, and a large folio book about a day’s wage for a laborer.

About two dozen centers of European printing existed in the early Reformation days. The city of Basel established itself as one early on (see p. 7). Centrally located between Germany, France, and Switzerland, and just north of the Alps with relatively easy access to Italy, it was a prime location for commerce—politically stable and exempt from imperial jurisdiction by the Holy Roman Empire. Basel fostered an environment of free economic and intellectual development that attracted many skilled trade workers and capable scholars.

From printers to reformers to kings

In Basel printers worked with reformers—and printing families worked together. Johannes Froben (1460–1527) owned the leading printing press in Basel; he came from Franconia, Germany, where he had learned the craft of printing in Nuremberg. In 1500 he married Gertrud Lachner, daughter of a bookseller. Froben quickly established himself as a high-quality printer of books in Latin, Greek, and even Hebrew.

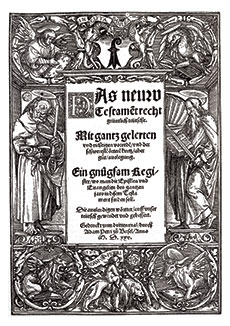

Froben was also a close friend of humanist Erasmus, who had settled (for the moment) in Basel and whose books he published. Froben rushed to press Erasmus’s groundbreaking critical edition of the New Testament in Greek. He occasionally collaborated with another Franconian, Johann Petri (c. 1497–1550), and with his nephew Adam Petri (1454–1527), who had followed his uncle to Basel.

The Petri press was arguably the second most important press in Basel. Adam Petri was one of the first printers there to collaborate with illustrators, including Hans Holbein (c. 1497–1543), whose fame spread as he painted portraits of everyone from Erasmus to Thomas More to Henry VIII and several of Henry’s wives.

Petri also helped advance the Reformation. Largely a religious printer, he printed over 80 editions of Luther’s works. He industriously issued an edition of Luther’s German translation of the New Testament in December of 1522, only a few months after its initial publication in Wittenberg. Perhaps even more ambitious was his attempted collection of Luther’s major works. On the title page of the first volume of a projected two-volume edition he wrote, “The second volume, God willing, should be issued after these better parts.” It never was.

Catholic theologian Johann Cochlaeus complained in 1521, “Nearly all printers are secret Lutherans; they do not print anything for us without pay and nothing reliable unless we stand beside them and look over their shoulders.” But not all printers worked well with Lutherans. Hans Hergot (d. 1527), who operated a press in the city of Nuremberg, was for Luther the epitome of a corrupt and untrustworthy printer. Luther referred to him as Hergetlein (“that little Hergot”), particularly funny since Herr Gott—literally “Lord God”—is the designation for God in German Bibles.

Hergot had a reputation of publishing pirated editions; he also had close sympathies with Thomas Müntzer and radical Anabaptists (see “A fire that spread,” pp. 28–32). In 1527 his press published a utopian tract, Of the new way of Christian life, which advocated a classless society and ran afoul of the political authorities. At the command of Duke Georg of Saxony, he was arrested and tried in the city of Leipzig, where he was executed.

A woman’s place is in the shop

Short life expectancy in the sixteenth century made it commonplace to remarry quickly. Hergot’s widow, Kunigunde (d. 1547), soon married rival printer Georg Wachter. In such situations it was usual for the two printing presses to merge and continue operations under the name of the male printer. But Kunigunde continued to publish under the name Hergot until 1539, keeping the business alive against many odds, rehabilitating it, and turning it into a respectable outfit.

The courageousness of this move cannot be overstated; a printing press with a bad reputation, whose owner had been executed for political reasons, marked for failure and bankruptcy, was now being run by a woman who did not even bother to conceal her gender. The world was indeed changing rapidly.

One of the most prolific female printers of the sixteenth century, Magdalena Kirsenmann, helped advance the Lutheran Reformation in Tübingen. She got into printing, like Kunigunde, after the death of her husband, Ulrich Morhart (c. 1490–1554). Through his first wife, Barbara, Morhart attained citizenship rights in Strasbourg and began printing there. In Tübingen he married his second wife, Katharina Zorn, who died only two years later. With Zorn’s dowry he financed his second press, the first permanent press in the city

of Tübingen.

As the only press in a university town, Morhart published many academic titles—which did not generate much income, although they did guarantee steady business. But in 1534 Duke Ulrich introduced Lutheranism, and his son Christoph instituted it as the state church, calling reformer Johannes Brenz (1499–1570) as one of his chief advisors.

Ulrich Morhart printed a catechism by Brenz in 1551 and also printed the first church order of the Duchy of Württemberg in 1553. Sources differ on whether Magdalena Kirsenmann was Morhart’s third or fourth wife, but she was certainly his last wife. After Ulrich’s death she printed a collection of statements by Martin Luther, treatises and commentaries by Brenz, and other Lutheran sermons and tracts.

In his 1521 letter, Cochlaeus complained that Reformation ideas were “so propagated and widely spread by the book printers that even tailors and shoemakers, indeed women and other simple idiots, who had accepted this new Lutheran gospel . . . read it eagerly, as if it were a fountain of all truth.” Luther put a more positive spin on it: printing was “God’s highest and extremest act of grace, whereby the business of the Gospel is driven forward.” Certainly the Reformation would not have been the same without it. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #118 The People’s Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Armin Siedlecki and Perry Brown

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #118 in 2016]

Armin Siedlecki is head of cataloging at Pitts Theology Library, Emory University. Perry Brown is a programmer at Truth for Life and formerly worked for the American Tract Society. This article is adapted from a talk given to the American Theological Library Association in 2014 and from “Preaching from the Print Shop” in CH 34.Next articles

Tearing down the images

Raids on churches resulted in the destruction of countless works of art

Jim WestA fire that spread

As soon as the Anabaptist movement began, it was persecuted

Walter Klaassen and John OyerThe accidental revolution

The English Reformation began with a king but took hold among a people

Melinda S. Zook