“Your daughters shall prophesy”

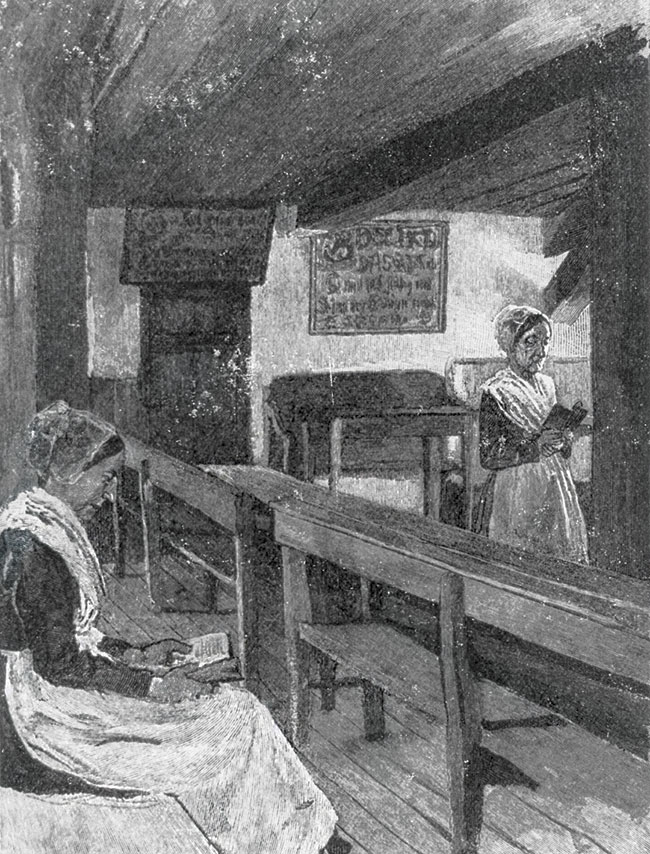

[Howard Pyle, Wood Engraving from “A Peculiar People,” 1889. Harper’s New Monthly—Prints and Photographs Division / Library of Congress]

Can you imagine a woman being put on trial for daring to host Bible studies in her home that included men and questioned the pastor’s sermons? Not only did Anne Hutchinson (1591–1643) endure this trial, she was found guilty. The Massachusetts Bay Colony ruled Hutchinson’s unorthodox practices “prejudicial to the state” and damaging to “honest” and “simple souls.” She argued that she was following “a clear rule in Titus 2:3–5, that the elder women should instruct the younger.” However, the court judged her “a woman not fit for our society” and banished her in 1638.

Quaker minister and missionary Elizabeth Webb (1663–1726) faced challenges too. Sensing herself called by God to share God’s universal love, Webb left her husband and nine children in England to sail to America in 1697. Two years later the Webb family moved to Philadelphia where Webb became the spiritual leader of the Concord Monthly Meeting.

Webb knew the Scriptures well and believed that women are neither spiritually weaker nor inferior to men. Her experiences as a wife, mother, minister, and missionary influenced her reading. Her verse-by-verse commentary on the book of Revelation circulated in manuscript form, the earliest known commentary by a woman in America. Although it was approved for publication, the Quaker press refused to fund it.

Colonial society gave frequent pushback against women who publicly interpreted Scripture. But as time went on, more American women used Scripture to preach and advocate for social reform and justice—and did not shy away from publishing their views.

“A fire shut up in my bones”

African American preacher Jarena Lee (1783–1864) infused her autobiography with biblical language. She opened her Religious Experience and Journal (1849) with an epigraph from Joel 2:28 (italics are hers): “And it shall come to pass, . . . that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh; and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy.” She also defended her right to preach with the example of Mary Magdalene:

Did not Mary first preach the risen Saviour, and is not the doctrine of the resurrection the very climax of Christianity—hangs not all our hope on this, as argued by St. Paul? Then did not Mary, a woman, preach the gospel?

Lee described her call to preach as “a fire shut up in my bones,” a phrase she drew from Jeremiah 20:9.

At age 19 Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896) confessed, “I was made for a preacher—indeed, I can scarcely keep my letters from turning into sermons.” She preached with her pen throughout her life. Though best known for Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), her most explicit work of biblical commentary is Woman in Sacred History (1873), which blends insights from traditional male scholarship—including that of her husband, Old Testament scholar Calvin Stowe (1802–1886)—with what she called “the gospel of womanhood.”

For example, her reading of Deborah’s ancient Hebrew poem in Judges 5:2–31 defended Deborah’s naming of the murderer Jael as the “most blessed of women” because Jael had “snared the tiger” Sisera and prevented the rape of many Israelite women (Judges 5:31). In The Minister’s Wooing (1859), Stowe had an illiterate slave demonstrate a woman’s scripturally based approach to pastoral care as more effective than a learned theologian’s:

I knows our Doctor’s a mighty good man. . . . But honey . . . sick folks [musn’t have] strong meat. . . . Look right at Jesus. . . . Don’t ye’ [remember] how He looked on His mother, when she stood faintin’ an’ tremblin’ under de cross, jes’ like you.

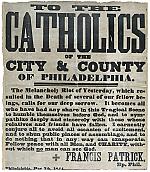

In 1860 renowned abolitionist and women’s rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) interpreted the Ten Commandments in a powerful political speech intended to rouse New Yorkers to act on behalf of slaves:

How can the beautiful daughter of a southern master honor the father who with cold indifference could expose her on the auction block to the coarse gaze of licentious bidders; or the ignoble slave mother, who could consent to curse her with such a life of agony and shame? Or, do you tell us, Sinai’s thunders were never meant for Afric’s ears?

Degrading women?

But over time Stanton came to view the Bible as an enemy rather than a friend of women. She envisioned a biblical commentary treating texts on women and texts excluding women. None of the women who agreed to be part of the project had theological training. When Stanton republished the resulting The Woman’s Bible in 1898, she added the essay “Bible and Church Degrade Woman.” Though many have praised her for contributions to “first wave” feminism, today Stanton also receives criticism for her elitism, racism, and tactics.

While privileged women like Stowe had access to biblical and theological resources through family members or supportive clergy, many others wanted a theological education for themselves to prepare for preaching and teaching. Antoinette Brown, later Blackwell (1825–1921), graduated from the Ladies’ Literature Course at Oberlin Collegiate Institute in Ohio in 1847 and petitioned for admission to Oberlin’s theological program. Granted only semi-official status, she challenged Oberlin’s sex-based standards for admission and its practice of not letting women speak in class.

Brown’s studies of the “master’s tools” of Greek, exegesis, church history, and theology equipped her to challenge traditional teachings limiting women’s roles based on Scripture. In an exegetical study of the Greek words lalein (to speak) and sigatōsan (let them be silent) from 1 Corinthians 14:34 in the Oberlin Quarterly Review in 1849, she concluded that Paul was not silencing all women for all time, but rather restraining the “kind of talking which was not profitable to the church.”

Brown completed theological studies in 1850 but was not granted a degree. Ordained in 1853 in the Congregational Church, she became a well-known author, speaker, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist. Eventually she turned Unitarian. Oberlin gave her an honorary master of arts degree in 1878—28 years after she completed her studies—and a doctor of divinity degree in 1908.

Mary Redington Ely (1887–1975) was one of few women before the mid-twentieth century to complete advanced studies in Bible and among the first to teach Bible at a college and seminary. Her journey through a male-dominated profession brought countless challenges. At her graduation from Union Seminary in 1919, she received a prestigious scholarship for graduate study at Cambridge, but was forced to sit with faculty wives in the balcony instead of with her male peers. Her Cambridge professors would not provide official transcripts showing that a woman had been in their theology classes.

TrailBlazer

While teaching religion at Vassar College, Ely completed her doctorate in New Testament at the University of Chicago magna cum laude in 1924. In 1926 she married her former professor, William Lyman. This opened up the possibility for her to teach part-time at a theological school, but when her husband retired, she said, “Union took it for granted that I would retire too.”

Instead, Ely served as dean and professor of religion at Sweet Briar College for women until a full-time position at Union opened up. This required her 1949 ordination in the Congregational Church, and she became the first woman to hold a full professorship and an endowed chair at Union. Union’s President Henry Pitney Van Dusen (1945–1963) eulogized her as “one of the ablest teachers of the English Bible in the United States, a distinguished New Testament scholar, and a leader in all matters connected with the life and work of women in the church.”

In the 1970s more colleges and seminaries began to train women for ordination and ministry and to allow them to teach subjects other than Christian education and biblical languages. Phyllis Trible (b. 1932), Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza (b. 1938), and other biblical scholars developed feminist approaches to reading Scripture—though they were later criticized by scholars including African Americans Renita Weems (b. 1954) and Clarice Martin (b. 1952) for failing to acknowledge that issues of race, class, and disability combine with gender to influence how we read Scripture.

Today the debate about women’s roles in interpreting and teaching Scripture remains a very live one (see p. 39). Despite this conflict women interpreters continue to call for revision and refinement in the writing of church history and theology.

CH

By Marion Ann Taylor

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #143 in 2022]

Marion Ann Taylor is professor of Old Testament and graduate director at Wycliffe College. She is the author of Ruth, Esther in the Story of God Bible Commentary series and of Handbook of Women Biblical Interpreters and coauthor of Voices Long Silenced.Next articles

Christian History timeline: A book for the church

How American Christians have interpreted, sung from, studied, taught, and sometimes fought over the Bible

the editorsOld book in a new world

The story of Bible translations in America centers around the KJV

Chris R. Armstrong