Andrew, James, and John

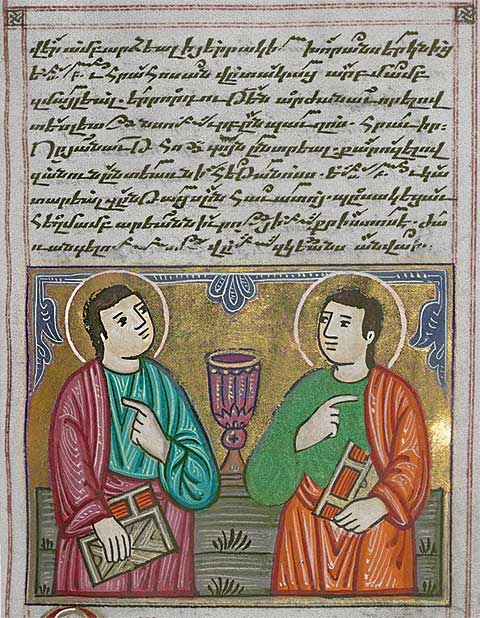

[Yakob Pēligratc‘i, Sts. John and James, Sons of Thunder, illustration in Hymnal, Walters Manuscript W.547, fol. 40r., 1678. Constantinople—Walters Art Museum]

While Jesus called each of the 12 disciples with loving purpose, the Gospels show his closer friendship with three in particular—Peter, the rock upon whom he built his church; James, the first apostle to die for him; and John, the disciple whom Jesus loved. Also occasionally included in this intimate group is Andrew, Peter’s brother. The New Testament tells some of their stories, but church tradition and apocryphal accounts share just how far their witness of the risen Savior reached.

ANDREW: THE FIRST DISCIPLE

Andrew, who was originally a disciple of John the Baptist, was ever the missional and relational disciple and as the first disciple of Jesus, introduced his own brother Peter to the Messiah. He seemed especially close to another disciple, Philip (both were from Bethsaida), as they attempted to find solutions to feed the large crowd of 5,000 (John 6) and later to connect a group of Greeks with Jesus (John 12).

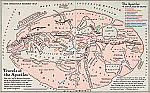

All the apostles were commissioned to take the gospel to the world, and Jerome states that each apostle died where he ministered. Third-century bishop Hippolytus (c. 170–c. 235) summarized Andrew’s mission in On the Apostles and Disciples: “he preached to the Scythians and Thracians, and was crucified, suspended on an olive tree, at Patrae [Patras], a town of Achaia; and there too he was buried.” Other texts indicate that he may have traveled with a partner, Matthias, with whom he witnessed in regions north of the Black Sea, under Scythian rule (see pp. 46–48).

Andrew returned south to Pontus and began a missionary journey westward across the cities of northern Turkey and further into Greece through Macedon and its major cities: Philippi, Thessalonica, and Patras (or Patara). As he traveled, Andrew worked the same kinds of signs and wonders as Jesus—healing, raising the dead, exorcisms, calming storms, and supernaturally defeating armed opponents. As Andrew preached the gospel, many people believed in Christ based on his testimony and miraculous authority.

At Patras in Achaia (Greece), Andrew was the object of the governor’s envy and malice; he executed Andrew by hanging him from a cross by the seashore. After three days Andrew breathed his last, still preaching to passersby or any who gathered near to him. Thus Andrew’s mission work of preaching, teaching, healing, and battling demons culminated in his crucifixion, in likeness to his Lord, between AD 60 and 70.

After his death some of his remains were removed to various locations around Europe, which still claim a connection to Andrew through his mission work. Several countries hail him as their patron saint including Russia, Ukraine, Turkey, and Romania, as the late Roman provinces of Scythia and Thrace are located between southern Romania and northern Bulgaria. Less likely is his connection to places further west like Scotland, although the tradition remains that some of his relics were moved there in the fourth century (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover).

JAMES: EARLY MARYTR

According to tradition, all 12 apostles were martyred except John. However, James—the brother of John—is the only apostle whose death is recounted in Scripture. Acts 12:2 records James’s beheading at the order of Herod Agrippa. We are not told why Herod ordered his execution, except that it was part of a larger campaign against the fledgling church.

James’s early martyrdom, along with his place within the closest circle of Jesus’s followers, might suggest that he was the movement’s leader. Some factors favored him over Peter and John—he was John’s older brother, he had not denied Jesus as Peter did, and his death at the hands of Herod Agrippa may be viewed as mirroring the death of John the Baptist at the hands of Herod Antipas.

Some scholars have even speculated that James, nicknamed “Son of Thunder,” had a fiery preaching style that led him to confront Herod (like John the Baptist), but Peter’s simultaneous arrest and a lack of details from Luke speak against such speculation. Tradition claims that James’s head is buried under the floor of a chapel inside the Armenian Apostolic Cathedral of St. James, which is built over the alleged site of his martyrdom in Jerusalem.

James’s death in 44 (the same year as Herod Agrippa’s death, Acts 12:23) has elicited some legendary attention. Eusebius cites sources claiming that James’s escort to trial, a scribe named Josias, was converted by James’s defense at the trial and martyred along with him, having also seen James heal a paralytic on his way there.

The book of Acts is silent about James’s actions apart from his brief local ministry. A tradition preserved in the collected apocryphal writings Pseudo-Abdias asserts that James and Peter traveled to Lydia in North Africa, where they performed healings and confronted idols before being arrested. The soldiers tasked with extracting confessions were supernaturally prevented from torturing them and were forced to release them. In the Latin Ethiopic tradition, James confronted two magicians, converting one named Philetus to the faith and helping him defeat the other in spiritual battle.

Probably the most famous but least likely tradition surrounding James’s ministry is related to his alleged travel to Spain. An anonymous medieval account, the History of Compostela, claims that in northern Spain, James was granted a vision of Mary, Jesus’s mother, seated on a pillar, encouraging him to continue his ministry in Spain and to build a church at the site of the vision. This vision was apparently the first Marian appearance, and the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Pillar is built over the site of the encounter. James then returned to Jerusalem, where he was martyred.

Another tradition claims James’s remains made it back to Spain, eventually to be housed in a shrine at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. This shrine is a major pilgrimage site and is accessed by the Camino de Santiago (Way of Saint James), a network of routes through France and northern Spain that culminate at the cathedral. The route contains indicators in the form of scallop shells symbolizing his miraculous sea voyage back to Spain.

JOHN: ELDER AND APOSTLE?

The apostle John’s life and ministry following the biblical period are difficult to trace, partly due to questions regarding his authorship of key New Testament works and to conflicting extrabiblical source accounts. Most New Testament scholars believe the author of John’s Gospel—the disciple Jesus loved—is indeed John, son of Zebedee, and the younger brother of James, both of whom Jesus nicknamed “Sons of Thunder.” Some scholars doubt that the apostle John is the same John who authored Revelation, 2 John, and 3 John, instead attributing these works to another figure, John the Elder.

These assessments impact our understanding of John’s ministry following Jesus’s Ascension, since John the Elder oversaw churches in Asia Minor (Turkey) and was exiled to the Greek island of Patmos, most likely during the reign of Domitian (81–96), though some think it was under Nero (54–68). Despite relatively recent misgivings, the apostolic authorship of Revelation received virtually unanimous support in the early church, including Justin Martyr (c. 105–165), Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–c. 215), Hippolytus, Origen, and Athanasius (293–373). If the apostle is also the Elder, then we can reasonably accept testimony regarding John’s advanced age at his death. The vast majority of evidence indicates he died in old age of natural causes.

The bulk of John’s ministry unfolded in Asia Minor (modern Turkey) at Ephesus, where, according to tradition, John also took with him Mary the mother of Jesus. Abdias claims John was chosen by lots to take the gospel to Anatolia, and the Acts of Philip places John in Hierapolis, rescuing Bartholomew from martyrdom (see pp. 35–37). The Acts of the Holy Apostle John offers the most information about John’s activities in Turkey, but as a gnostic-leaning text, it is considered the least reliable, despite its second-century date.

In it John travels first to Miletus and then on to Ephesus around 48, where he establishes a church. He endears himself to the Ephesians by first healing the governor’s wife, Cleopatra, and then by raising the governor himself from the dead and healing many other people. His fiery preaching shatters the altar at the Temple of Artemis (Diana), and her priest is killed when the roof collapses. The people respond in faith, awed by “the God of John,” and pledge to worship the Lord. During John’s second tenure in Ephesus (after exile), he demonstrates to pagan leaders the power of the true God by remaining unharmed, drinking a poison that killed two other prisoners.

Legends attesting his miraculous deliverance from martyrdom in Rome and his peaceful death in Ephesus are not confined to Gnostic texts. Tertullian wrote of John’s miraculous survival of being boiled in oil in Against Heretics (see p. 27; pp. 30–33). Referencing this story alongside Peter’s crucifixion and Paul’s beheading suggests that it had widespread acceptance among early church leaders, who almost unanimously accepted that John lived into Domitian’s day and suffered under his authority.

A less reliable account claims Domitian unsuccessfully tried to poison John prior to his execution attempt. In a more fantastical account of John’s death, his body is translated to heaven and a fountain emerges at his burial site (Acts of John). Nonetheless Irenaeus, Eusebius, and Jerome claim that John died in old age and was buried at Ephesus. Today pilgrims can visit the supposed site of John’s burial in Selcuk, Turkey (near Ephesus), at the ruins of the Basilica of St. John, where archaeologists have confirmed a tomb below the ruins that dates to at least the second century. CH

By Stefana Dan Laing

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #156 in 2025]

Stefana Dan Laing is associate professor of divinity and theological librarian at Beeson Divinity School of Samford University. She is the author of Retrieving History: Memory and Identity Formation in the Early Church.