Not only what was believed but what was done

PROTESTANTS AND CATHOLICS during the Reformation and the years after pursued all kinds of reform vigorously: in doctrine, worship, and morals. They saw reform of personal conduct as just another part of the needed reform of the Christian faith. Girolamo Savonarola, Martin Luther, Desiderius Erasmus, Katharina Schütz Zell, Marguerite de Navarre—these leading preachers, writers, and rulers cast their morality net very wide. Clergy and laity, church and society, men and women, child and adult, family and individual were all on the judgment seat.

With the closing of many of the convents and monasteries, Europe and (eventually) the New World witnessed a profound change in thinking on the nature of work and the understanding of marriage. The societal unease this caused added to an already-increasing concern people had about witchcraft. Those seeking to purify the morals of society were forced to confront what they saw as a growing plague, and they did not hesitate to employ executions as a means to purge the body politic.

Magic, bell-ringing, and profit

What kind of sins came in for censure? A century after the Reformation, John Bunyan, English author of The Pilgrim’s Progress, recorded his conversion to the Christian faith in his 1666 autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners. There he confessed to bear-baiting, bell-ringing, dancing, and playing games on Sunday. Also common at this time were astrology, necromancy, and other forms of esoteric magical practice, not to mention drunkenness, adultery, and heresy. One of the most common sins associated with the clergy was simony: the selling or buying of church-related offices or, more generally, the making of profit off of sacred things.

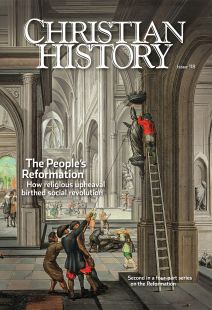

Order Christian History #118: The People’s Reformation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Moral reform was not just the work of lone individuals; it was taken seriously enough that some banded together in an effort to fight immorality. In France, for instance, groups like the Holy League, started by a nobleman named Henry, Duke of Guise, worked to stamp out what they saw as the heresy of Protestantism (specifically the presence of Calvinists) within the country—on the grounds that this was a moral ill and made France liable to the judgment of God.

This purifying work also included governments and churches, who labored together to stamp out vice. French reformer John Calvin worked to reform the faith and morals of his adopted home, Geneva, by founding a quasi-governmental body called the Consistory. Made up of both Christian ministers and political officials, the Consistory’s job was to police the morals of the city.

Everything from slander to financial improprieties and murder fell under its jurisdiction. The Consistory met each Thursday to hear cases. Like the Spanish Inquisition, the Consistory was governed by rules that allowed those falsely accused to extricate themselves from the charges brought against them.

Much more on Calvin and Geneva coming in issue 120!—The Editors

This article is from Christian History magazine #118 The People’s Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Jon Balserak

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #118 in 2016]

Jon Balserak, senior lecturer in early modern religion, University of Bristol.Next articles

They wanted God to save his own

Had Luther argued only for spiritual changes? German peasants didn’t think so

Edwin Woodruff TaitPreachers and printers

A hot-off-the-press technology pushed the Reformation forward

Armin Siedlecki and Perry BrownTearing down the images

Raids on churches resulted in the destruction of countless works of art

Jim WestA fire that spread

As soon as the Anabaptist movement began, it was persecuted

Walter Klaassen and John Oyer