They wanted God to save his own

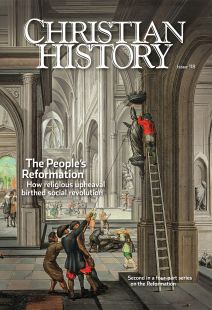

The explosive ideas of Martin Luther landed in a world already tense with conflict and rife with agendas of social and religious reform. Centuries-long tension between wealthy landowners and the peasants who made up the bulk of the population exploded in a series of massive revolts in 1524 and 1525 all over southern and central Germany and parts of Switzerland. The conflict would leave serious scars on Luther’s reputation as hundreds of thousands of people organized into local “bands” or armies in opposition to the landowners.

Upwardly mobile Luther

The term “peasant” (Bauer in German) referred not only to farmers but to miners and craftsmen as well. Luther himself came from a “peasant” family, although his father was a successful entrepreneur who owned a factory and married the daughter of a lawyer from the city. Luther’s kind of social mobility was by no means unheard of in the sixteenth century. Serfdom, which had tied the peasants to their land in the earlier Middle Ages, was disappearing, and a money-based economy slowly emerging.

In the fourteenth century, the Black Death had decimated Europe’s population, killing as many as 200 million people. This led to shortages in labor and a resulting improvement in the lot of peasant workers (though, given the high mortality rate, one historian quipped that the fifteenth century was the “golden age of the bacteria,” not of the worker). But by 1500 the population had climbed to preplague levels. Combined with the influx of gold and silver from the New World, the rise in population led to increased prices. For landowners, who often received payment in kind and whose income was fixed by custom, this created a huge problem, as their expenses were going up while their incomes were not.

As less successful people lost their lands and positions, those at the very top of the social hierarchy gobbled up more and more land. These highly privileged elites, with a growing hunger for luxury goods as status symbols and often with massive debts to banking companies, had every incentive to squeeze their tenants financially.

In the early sixteenth century, traditional peasant rights disappeared in one region after another. Grazing land, once available for all members of the community, was taken by the lord as his own property to be used for large-scale commercial farming. Peasants were denied traditional rights to fish and hunt, and rents went up steeply.

From 1490 on peasants revolted against these newly unfavorable conditions in what were called the Bundschuh revolts, named for the peasant shoe that the rebels used as a symbol. Rebels argued that the nobility’s land-grab did not just violate traditional rights and customs, but contradicted divine justice.

This notion of “godly justice” or “godly law” was based on the widely accepted medieval concept of “natural law.” According to Thomas Aquinas, natural law is an eternal expression of God’s mind—the absolute standard by which all human laws should be measured. Any law that contradicts natural law is no law at all. “Godly law,” as invoked by the rebels, is natural law “weaponized.”

Desperate men who raised armies and issued demands took it out of the academy and into the lanes and hedges of early modern Germany.

Order Christian History #118: The People’s Reformation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Fighting for the pure gospel

The rebellions of 1524–25, larger and better organized, also now had a new ideological framework for the appeal to godly law: the concept of the “pure Gospel” taught by Luther and other reformers who claimed that when the true sense of Scripture was believed and understood, it would radically transform the face of Christian Europe. This key Gospel message was the revelation that divine Gerechtigkeit, “righteousness” or “justice,” is a free gift received by faith.

As this message spread across Germany through pamphlets written in the vernacular, it became a message not only of religious but also of social and political reform. Chafing under oppression by both religious and political elites, rural and urban commoners eagerly read Luther’s three radical treatises of 1520.

The first, Luther’s Letter to the German Nobility, called on the aristocracy to take up the mantle of reform, blaming church and society’s problems on oppressive and unbiblical behavior of popes and Catholic clergy. His treatise on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church argued that the sacraments had been corrupted from their true intention and abused to serve the power and interests of the clergy. And most powerfully, his treatise on the Freedom of a Christian declared that a true Christian is a “free lord,” “subject to none,” and at the same time the servant of all through love.

Luther proclaimed that faith in Christ frees the believer from human rules that claim to bind the conscience. A Christian is no longer to do right out of fear of punishment but rather out of spontaneous love for the neighbor. His message affirmed the dignity of the humblest Christian in the humblest of callings, who by acting out of love could serve as Christ to others.

The peasants were listening.

The 12 Articles adopted in March 1525 by rebels in the region of Swabia (one of the areas where the revolt was strongest) explained that the rebellion was not about overthrowing authority but rather about establishing legitimate authority on the basis of the Word of God:

The peasants demand that this Gospel be taught them as a guide in life, and they ought not to be called disobedient or disorderly. Whether God grants the peasants (earnestly wishing to live according to His word) their requests or no, who shall find fault with the will of the Most High? . . . Did he not hear the children of Israel when they called upon Him and saved them out of the hands of Pharaoh? Can He not save His own today? Yes, He will save them and that speedily.

“Christ has redeemed us all”

The Articles protested against excessive forced labor demands and the restriction of traditional rights to hunt, fish, and cut wood, but they also called for rural communities to have the right to appoint and support their own pastors, rather than sending money to ecclesiastical lords who cared little for the welfare of the people over whom they exercised authority.

The most pointed articles protested against the institution of serfdom, once again growing in the German lands after centuries of slow decline:

Christ has delivered and redeemed us all, without exception, by the shedding of His precious blood, the lowly as well as the great. . . . It is consistent with Scripture that we should be free and wish to be so. Not that we would wish to be absolutely free and under no authority. God does not teach us that we should lead a disorderly life in the lusts of the flesh, but that we should love the Lord our God and our neighbor. . . . We are thus ready to yield obedience according to God’s law to our elected and regular authorities in all proper things becoming to a Christian. We, therefore, take it for granted that you will release us from serfdom as true Christians, unless it should be shown us from the Gospel that we are serfs.

Luther found the Articles moderate in purely secular terms, but as a religious text utterly mistaken, even blasphemous. For him the Gospel could never serve as the basis for political demands: the freedom brought by Christ is an inner freedom. The believer is freed from sin, death, the devil, and even the law’s coercive commandments, but the “justice” given to believers by Christ had nothing to do with hunting and fishing rights.

That did not mean that the Gospel has no implications for social relationships. It implied that the believer should give up all claims to his or her own rights and interests, humbly serving the neighbor in love.

Luther accused the peasants of having entirely missed this part of his teaching, but the Articles made clear that the authors envisioned a society in which this kind of loving service to the neighbor formed the basis for law and all social relations. From the standpoint of the revolutionaries, Luther’s view of “love of neighbor” amounted to an endorsement of the unjust status quo keeping the peasants bound in serfdom.

Other reformers, such as radical priest Thomas Müntzer, became a voice for the peasants’ concerns. Initially an admirer of Luther, who had recommended Müntzer to pastoral positions, by 1523 Müntzer had become deeply disillusioned with the Wittenberg model of reform. In 1524, after Luther had called Müntzer a “satan” and urged the German princes to shut him down, he published an attack on Luther. The title says it all: A Highly Provoked Defense and Answer to the Spiritless, Soft-living Flesh at Wittenberg who Has Most Lamentably Befouled Pitiable Christianity in a Perverted Way by His Theft of Holy Scripture.

Where Luther left coercive force to the lawful rulers and saw the job of the church as proclaiming the healing gospel of God’s forgiveness, Müntzer believed that the true Gospel includes proclaiming God’s law written on the heart through the power of the Spirit.

Müntzer argued that the real dichotomy is not between law and Gospel but between those who are guided by the Spirit and those who are not. He saw Luther’s doctrine of justification by faith as a way of letting false Christians off the hook. The power of the sword, according to Müntzer, was given not just to princes but to the whole Christian community. Those who have the Spirit and truly seek to follow God’s law are the true church with both the right and the duty to punish the wicked and establish God’s true justice.

Headed for destruction

Müntzer expressed all this in a famous sermon before Elector John of Saxony (Luther’s patron and protector) and other powerful German nobles in July 1524. Preaching from Daniel 2, Müntzer proclaimed the coming of God’s kingdom, the “stone cut from a mountain without hands” destined to destroy all merely human kingdoms and fill the world.

The princes had a choice: they could submit to the Holy Spirit and be agents of God’s kingdom, punishing the wicked (oppressive upper classes, whether clerical or lay) and establishing God’s true justice—or they could cling to worldly authority and be swept away themselves. When the revolution broke out a few months later, Müntzer enthusiastically supported it and led a band of 300 men to the disastrous battle of Frankenhausen in May 1525, where the revolt was finally crushed (as was Müntzer).

Meanwhile in April 1525, one peasant army called the “Bright Band,” led by “Little Jack” Rohrbach, captured the castle of Weinsberg and killed its lord by making him run a gauntlet of pikes (long spears). Rohrbach was subsequently deposed by his own forces and replaced with a more trustworthy commander.

But for Luther, who was getting all his news from sources hostile to the peasants, the killing of one noble prisoner on the part of the rebels was a noteworthy atrocity, while the massacre of entire bands of peasants was standard procedure. As the rebel armies, made up solely of poorly trained infantry, were trounced in battle after battle, the death toll mounted to around 100,000.

Among the dead at Frankenhausen was Müntzer, who had promised to “catch all the bullets in his coat,” but instead fled the carnage and was captured and executed. But the dream of a revolution to establish God’s kingdom did not die with him. Radical Christian visionaries, to whom the name “Anabaptist” soon applied (see “A fire that spread,” pp. 28–32) continued to predict that the end was near and that Christ was establishing a new kingdom of justice and equality.

Whether Luther liked it or not, godly law had been weaponized, and centuries would hear the echoing message in political as well as religious realms: “Can He not save His own today? Yes, He will save them and that speedily.” CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #118 The People’s Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Edwin Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #118 in 2016]

Edwin Woodruff Tait is contributing editor at Christian History.Next articles

Preachers and printers

A hot-off-the-press technology pushed the Reformation forward

Armin Siedlecki and Perry BrownTearing down the images

Raids on churches resulted in the destruction of countless works of art

Jim WestA fire that spread

As soon as the Anabaptist movement began, it was persecuted

Walter Klaassen and John Oyer