BONUS ONLINE CONTENT: What’s in a name?

IT'S THE NAME by which about one-third of the world’s Christians call themselves. But when it first arose in the 16th century, that fact would probably have surprised those to whom the name was first applied.

In 1529, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, convened the Second Diet of Speyer to try to bring about religious unity in the face of a Turkish threat to the eastern part of his empire (he ruled in present-day Spain, Germany, Austria, and Hungary.) Both Catholic princes and those sympathetic to the reforms of Luther and Zwingli attended. (A Diet is basically a formal legislative meeting.)

Three years previously, another Diet had been called at Speyer in 1526. Presided over by Charles’ brother, Archduke Ferdinand I of Austria, that Diet had negotiated the temporary suspension of the Edict of Worms condemning Luther and his writings until such time as a general council could be called to deal with the new Reformation movement. At the Second Diet of Speyer, however, Ferdinand—displeased with the progress that Luther’s ideas had made in the interim—and the Roman Catholic princes decided that the Edict of Worms would be enforced and that Catholicism should be the religion of the entire Holy Roman Empire.

Six Lutheran princes and the leaders of fourteen German “free cities” decided they would argue this decision. On April 20, 1529 they wrote a “Letter of Protestation” which, since Ferdinand refused to allow it to be read, they had printed and distributed. Then, on April 25, they filed a formal appeal called the “Instrument of Protest” to either the Emperor, a yet-to-be-called general council, or a synod of the German nation explaining that they refused to abide by the majority decisions of the council. From these actions arose the name “Protestant.”

Despite its common use today, it was by no means the most common name for those who opposed Catholicism in the 16th century. German reformers called themselves “evangelicals,” French “Huguenots,” and Swiss “Reformed.”

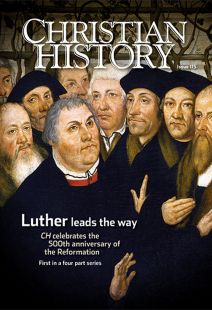

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is managing editor of Christian History.Next articles

BONUS ONLINE CONTENT: The road not taken II

Cardinal Contarini and the Colloquy of Regensburg

David C. SteinmetzBONUS ONLINE CONTENT: The unlucky cardinal

Reginald Pole might have been Queen Mary’s husband or a reforming pope. Instead, he lost everything

David C. SteinmetzBONUS ONLINE CONTENT: This is my body, argued for you

How do we meet Jesus in the Eucharist? Everybody in the 16th century seemed to have a different idea

David C. SteinmetzBONUS ONLINE CONTENT: Recovering the past

Christian humanists believed in continuity between classical wisdom and Christian truth

Jennifer Trafton and Jennifer Woodruff Tait