The life and thought of Zwingli

HULDRYCH ZWINGLI (1484–1531) was born on New Year’s Day, seven weeks after Luther. His family lived in Wildhaus, Switzerland, where his father was a farmer and a magistrate. After preparatory school in Basel and Bern, he attended the universities of Vienna and Basel. There teachers, including Thomas Wyttenbach (1472–1526), later a Swiss reformer, introduced him to humanist studies and scholastic theology.

Zwingli’s earliest work, a patriotic poem, attacked mercenary military service. Experience of war as a chaplain in 1513 and 1515 intensified his attacks and provoked opposition in Glarus, where he had been a priest since 1506. The books he bought and read there show his love of Greek and Roman antiquity.

In 1515 or 1516, he met Erasmus, who pointed him to Christian antiquity—Scripture and the church fathers—in a new way. Zwingli bought editions of works by the fathers and learned the Greek New Testament by heart. He moved to Einsiedeln, a center of Marian devotion, and two years later to Zurich.

Preaching to their needs

Zwingli became a reformer sometime between 1516 and 1522, probably independently of Luther. On January 1, 1519, he began to preach through Matthew rather than on the assigned passage for the day; he then moved on to other biblical books related to the people’s needs rather than the lectionary schedule. He later spoke of various influences moving him toward reform: Paul, John, Augustine’s writings on John, his teacher Wyttenbach’s rejection of indulgences, and a poem by Erasmus showing Christ alone as mediator. His near-death experience with the plague in August 1519 may also have contributed.

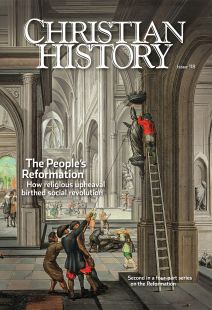

Order Christian History #118: The People’s Reformation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

In 1520 the city council in Zurich resolved that preaching be measured by the Scriptures; in 1522 Zwingli broke the Lenten fast and appealed that clergy be allowed to marry (he had already secretly married Anna Reinhard, so this was no academic question). In January 1523 the council summoned the First Disputation to see whose teaching would prevail on disputed issues. Zwingli defended his teaching as scriptural in the form of 67 theses and was vindicated. The council’s support of the Reformation was vital.

The Second Zurich Disputation in October 1523 declared church images and the Mass unscriptural. In 1524 statues and images were removed (see Tearing down the images,” p. 25), and in 1525 the Lord’s Supper replaced the Mass. A Latin school called the “Prophecy” was founded to re-educate and retrain clergy (and some laypeople) through translation, exposition, and preaching of the Bible.

Some in Zurich were more radical than Zwingli on social issues, government, the church, and baptism. Called Anabaptists, they suffered exile or death by drowning (see “A fire that spread,” pp. 28–32). Luther differed on the Eucharist with both groups, leading to prolonged controversy. At the Marburg Colloquy, Luther refused fellowship with Swiss reformers because he believed in the bodily presence of Christ in the Eucharist and Zwingli did not (see “Allies or enemies,” pp. 15–17).

Zwingli’s theology focused strongly on God’s majesty. He emphasized providence and election and drew sharp distinctions between creator and created, Christ’s divinity and Christ’s humanity, signs and things signified. He contrasted faith in the creator with faith in created things (including works and sacraments), affirmed the unity of Scripture, supported the role of government in church affairs, and developed the doctrine of baptism as God’s covenant with us. Today his spiritual descendants are found in Reformed churches worldwide.

This article is from Christian History magazine #118 The People’s Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By W. P. Stephens

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #118 in 2016]

W. P. Stephens, author of Zwingli: An Introduction to His Thought; Theology of Huldrych Zwingli; and The Holy Spirit in the Thought of Martin Bucer.Next articles

Allies or Enemies?

The Reformers soon divided over crucial issues; Luther himself was one reason why

Robert D. LinderNot only what was believed but what was done

Reformers wanted to change behavior, not just doctrine

Jon BalserakThey wanted God to save his own

Had Luther argued only for spiritual changes? German peasants didn’t think so

Edwin Woodruff TaitPreachers and printers

A hot-off-the-press technology pushed the Reformation forward

Armin Siedlecki and Perry Brown